We Shape Our Buildngs

The physical environment is a key component of a systemic approach to meeting the cultural challenge of patient safety in modern healthcare design.

Hospitals are complex. The physical environment in which that complexity exists has a significant impact on health and safety. However, enhancing patient safety or improving quality has not been integrated into aspects of the design of hospital buildings. Despite recent discussions in architectural literature regarding design of ‘patient-centred’ healthcare facilities and ‘evidence-based design’, there has been little assessment of the impact of the built environment on patient outcomes.

|

|

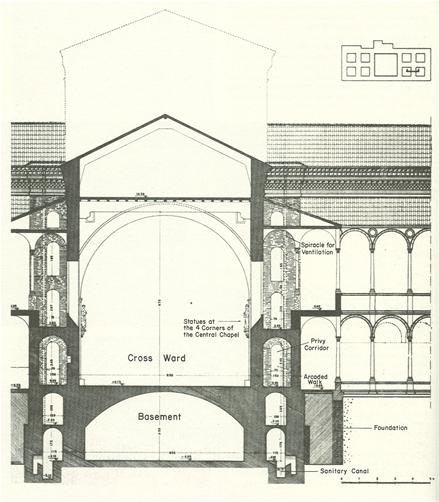

| Figure 1: Ospedale Maggiore, Milan, section by Liliana Grassi |

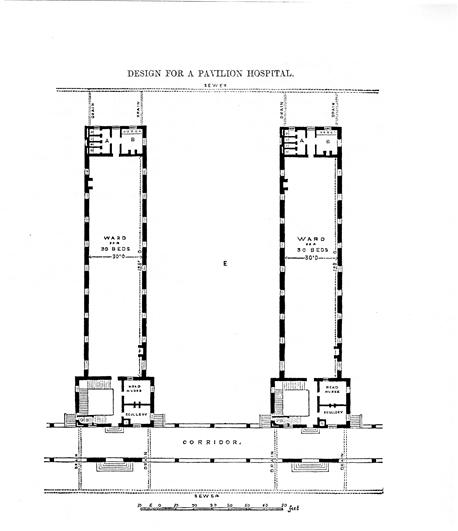

Figure 2: British army hospital, Renkioi, plan by Isambard Brunel, from Longmans Green |

Studies have focused primarily on the effects of light, colour, views, and noise, yet there are many more considerations in facility planning that can influence the safety and quality of care1.

Analysis of more than 400 research studies shows a direct link between quality of care, patient health, and the way a hospital is designed. Here are a few examples of how changes in design can improve the quality of care:

• Patient falls declined by 75% in the cardiac critical care unit at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis, Indiana, which made better use of nursing staff by dispersing their stations and placing them in closer proximity to patients’ rooms1;

• The rate of hospital-acquired infections decreased 11% in new patient pavilions at Bronson Methodist Hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan which was attributed to a design that featured private rooms and specially located sinks1;

• Medical errors fell 30% on two new inpatient units at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit, Michigan, after it allocated more space for their medication rooms, re-organised medical supplies, and installed acoustical panels to decrease noise levels1.

The evidence is impressive. The healthcare environment has substantial effects on patient health and safety, care efficiency, staff effectiveness and morale. The US spends approximately 17% of its gross national product on healthcare, much of which is provided in hospitals. Yet, despite this enormous expenditure and the available technological resources, today’s hospital care frequently runs afoul of the cardinal rule of medicine – above all else, do no harm.

Hospitals also create stress for patients, their families, and staff. The negative effects of stress are psychological, physiological, and behavioural, and include:

• Anxiety, depression, and anger (psychological);

• Increased blood pressure, elevated levels of the body’s stress hormones, and reduced immune function (physiological); and,

• Sleeplessness, aggressive outbursts, patient refusal to follow doctor’s instructions, staff inattention to detail, and drug or alcohol abuse (behavioural).

Poor design of the hospital environment contributes to all these problems. Poor air quality and ventilation, together with placing two or more patients in the same room, are major causes of hospital-acquired infection.

Inadequate lighting is linked to patient depression as well as to medication errors. Lack of a strong nursing presence can result in patient falls. Seldom does an opportunity emerge to build a new hospital; most hospitals are in a continuous cycle of remodelling and expanding their existing facilities to adapt to changing demands. The US is in the midst of the largest hospital construction boom in history with over 500 hospitals being built, with a staggering $200 billion impact.

We would then ask ourselves several guiding questions:

• How and via what mechanisms does the physical environment participate in patient safety?

• How does the environment of the system affect the safety of patients?

• What characteristics are used to describe an environment?

• What process creates the physical environment?

• Is it possible to change either the creation process or the result to improve safety?

|

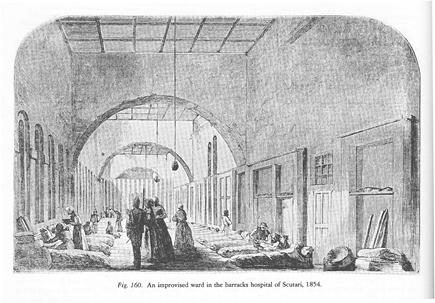

Figure 3: Example of a Nightingale Ward,

from Notes on Hospitals, Florence Nightingale |

Healthcare building design history

Louis Sullivan’s famous dictum, “form follows function”, should be rewritten to say, “form follows function and then function follows form”2, to express the essential relationship between buildings and the people who populate them. The act of making form follow function (or clinical process) is brief, fraught with difficulties and often incomplete.

The opportunity or limitation placed by the form upon function is lasting, hidden and inelastic. And the lengthy process of 5-8 years from idea inception to facility construction exacerbates these challenges. In 1976, John Thompson and Grace Goldin of Yale University wrote the most complete study on the history of hospital design, A Social and Architectural History of the Hospital.

While this work principally deals with the development of nursing wards or units, it sheds light on other key aspects of hospital development. The historical aspect of the work can be summarised as follows: there is nothing new under the sun. The two essential problems of hospital design which architects still face are: efficient and safe removal of human waste and creation of an environment that aids rather than hinders healing. Several examples will follow to demonstrate the slow pace of change in healthcare design.

Greek hospitals – Patient-focused

The first of these, though perhaps not the first hospital, is the Greek Asclepieion. These institutions were as much, if not more, temples than hospitals. Patients received the benefit of prayers and sacrificial offerings which were intended to influence the god of healing Asclepius. The relationship between god (healer) and patient with attendants as intermediaries was paramount.

Roman hospitals – Specialty hospitals

The Romans adopted the Asclepian model, but reformatted it to their own more practical purpose. Since soldiers, and later slaves, were the foundation of Roman civilization, it was natural that they should build valetudinaria to serve the legions. These might be complicated fixed facilities where Roman rule was well established, or they might be small or movable structures to accommodate armies on the march.

As the expansion of the empire decreased, captured slaves became less common and Roman slaveholders were obliged to take better care of their property. One answer was to adopt the military approach and build valetudinaria for slaves. Better-heeled elements of Roman society had no such institutions available, since the belief structure held that illness was due to the anger of the gods and not natural causes.

The Middle Ages – Charity care

During the Middle Ages, as Christianity spread through Europe, the concept of caring for less fortunate members of society became more popular. In Islamic countries, value was even placed on the human body with the concomitant concept of caring for it, whereas Christianity looked at the body as a repository for the soul.

Great pilgrimages and the Crusades occasioned the development of centres to care for travellers. Located at monasteries such as Cluny in France, these developed from adjunct functions to purpose-built components of the monastery complex.

The technology of care in these institutions had not made great strides since the days of the Greeks, nor had there been great advances in the methods of removing waste or designing wards that aided healing. Clearly, however, there was a growing interest in health and public health, including creating the types of organisations and institutions that should be responsible for public welfare.

During the Renaissance, designers continued to struggle with the problems of waste removal and ward design. Some solutions, such as the hospital planned by Filarte in Milan (Figure 1), had a well-developed system of latrines near patient sleeping areas.

Unfortunately, the waste, once removed, was discharged into the principal public waterway, which only relocated, rather than solved, the problem. In Filarte’s ward plan, the latrines were located adjacent to patient beds. Wards were also designed so that patients could see the altar of the patron saint.

The advent of scientific medicine

During the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the balance between religiously dominated belief systems and naturalistic driven belief systems (science) underwent a pronounced change. As the bulk of scientific knowledge grew, there was greater interest in experimentation in health facility design. Human understanding of disease had changed and was forcing new concepts in care in areas such as antisepsis, surgical interventions and other drug developments. In many places, it was still common to have more than one patient per bed and care was more palliative than remedial. Mental health conditions were still misunderstood, and although there were some new models of mental healthcare, mental health conditions were felt to be due to demonic and/or satanical influences. War and military conquests also helped to spur dramatic changes in care.

|

Figure 6: Turkish barracks at Scutari,

Illustrated London News, 16 December 1854

|

Florence Nightingale

Few stories are more significant in the history of healthcare than that of Florence Nightingale and her experience during the Crimean war. At the converted Turkish barracks at Scutari which the British army used as a hospital (Figure 6), the mortality rate in the hospital is said to have been 47% with infection killing many more soldiers than bullets.

The answer developed for Scutari was a modular hospital solution that could be constructed in England, disassembled, shipped to Turkey, and reassembled (Figure 2). In addition, it was cheap and made of materials which could be easily cleaned.

The patient wards, individual huts for about 50 men, had other unique features, including a ventilation system which forced 1,000 cubic feet of air per minute through two ducts underneath the floor. The air was discharged into the ward through grilles in the floor and travelled upward and out. The hospital was a combination of ward huts and special-purpose structures for cooking, cleaning, and other aspects of care and operation all organised in a grid-like layout which facilitated the placement of water supplies and drains.

An innovative ward plan, founded on a 30-foot wide unit and housing 30 patients, was derived from the Crimean experience, and came to be known as the ‘Nightingale Ward’ (Figure 3).

Modern hospital design process

Global performance, in terms of outcome, risk management, and safety, is influenced by local interactions and synchronisation of system components (e.g. providers, patients, technologies, information and material resources, physical and temporal constraints).

As a result, adverse events and unintended consequences are impossible to understand in terms of simple rational rules. To date, reductionist approaches towards hospital construction have failed to adequately control risk or reduce the number of adverse events. The conditions in which we work, with fatigue from 24-hour duty rotations, double shifts, high workloads, confusing labels, noisy environments, look-alike names, poor handwriting, poorly designed equipment, and healthcare buildings, can lead to errors.

These are open or ill-posed problems best understood through controlled observations, cases study, and modelling, with insights drawn from other complex adaptive systems, such as emerging economies and dynamic social systems. This complex system theory can arguably be used as the basis for a new principled approach to optimising hospital design, performance and outcomes, managing risk and guiding health policy.

The traditional hospital design process requires that architects be given programme objectives (function and programme), which are then translated in room requirements (a space programme) and followed by the creation of department adjacencies (block diagrams). Once this preliminary information has been provided, room-by-room adjacencies are developed and then a detailed design of each room is completed (schematic and design development).

Architects then convert room-by-room design to construction documents that represent how individuals, equipment and technology in hospitals will function together. Equipment and technology planning generally occurs in the later stages of the design process. Typically, discussions of patient safety or designing around adverse events are rare.

This creates an opportunity to repeat latent conditions existing in current hospital designs that contribute to active failures (adverse events or sentinel events)3. Human factors, the interface and impact of equipment, technology, and facilities is also not typically discussed or explored early in the process.

Patient safety challenge

In the early 1990s, researchers such as Leape and Brennan began to question the safety of healthcare institutions4. The Institute of Medicine report in 2000 posited that between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans die in US hospitals due to preventable errors.

There are two possible responses to this challenge – a personal or a systems approach. Our primary response to this epidemic has been to focus on the personal approach in which after an error or accident we search for the ‘guilty parties’. The legal system is most willing to help in this ‘righteous cause’ as it rids the system of ‘incompetent doctors’ and punishes ‘bad hospitals’.

The concept of ‘systems’ is important in the discussion of healthcare safety and health facility design. A system is a set of components, sometimes called subsystems or microsystems, which are related or a complex whole formed from related parts, or an organisation of people, tools, resources and environment5.

This last term, ‘environment’, is the focus of this study – specifically the physical environment in which components are housed, as opposed to the cultural environment.

|

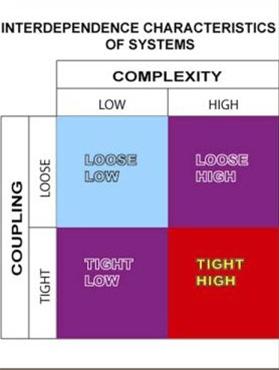

| Figure 4: Interdependance characteristics of systems (after Perrow6 |

Characteristics of systems

A healthcare system includes several sub-component microsystems. The foremost are the medical or clinical processes undertaken. Another component is medical and nonmedical technology, including information systems, diagnostic systems, imaging systems and more mundane technologies such as floor cleaning equipment, supply ordering and distribution technologies.

Next there is organisation, the administrative arrangement that includes policies, procedures, strategies and tactics, management tools and business plans. Humans are another subsystem, which includes professional, technical, administrative, management, patient, public and government. Finally, the designed, built environment is a subcomponent. It possesses a large number of characteristics.

Charles Perrow undertook a study of major accidents and discovered that systems, rather than individuals, were often at fault6. Perrow and James Reason redefined how we should proceed to understand causes of accidents and fix problems. One of Perrow’s contributions was to describe how the components of systems relate. He defined two scales – complexity and coupling – which explained how components of systems react (Figure 4).

Complexity can range from low complexity to high complexity. Making a sandwich is a low complexity undertaking. Flying a fighter jet off an aircraft carrier is highly complex. Coupling ranges from loose to tight. If an activity is not highly dependent on the exactness of preceding activities, it is loosely coupled.

The steps of making a sandwich are loosely coupled. The steps in flying off the carrier are tightly coupled. Healthcare, for example, is a system that is highly complex and tightly interrelated, with many subcomponents, and some hidden characteristics, requiring ‘operators’ to use a great deal of short-term memory or computing power.

Healthcare systems are also tightly coupled in that there is no ‘wiggle room’ in the connections. If one component fails, the adjoining components are immediately impacted, sometimes in unforeseen ways. The illustration above shows the relationships between complexity and coupling7.

|

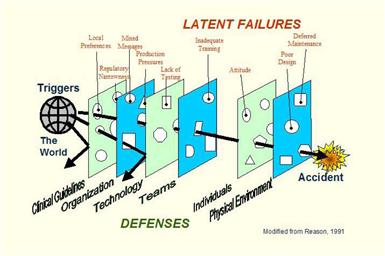

Figure 5: Layers of defence systems breached through their latent failures (after Reason8)

|

Reason’s theory of human errors

Reason, in his work Human Error8, teaches that accidents are latent in systems. This idea speaks to the imperfection of the design of systems as much as to the fallibility of the people who operate them. Reason describes a system as having a series of layers of defence (Figure 5).

These might be procedures, training, teams, organisation and technical safeguards. These safeguards, however, are imperfect. They each have holes like a piece of Swiss cheese. The holes represent various types of shortcomings peculiar to each layer of defence. The location of the holes in each layer is dynamic as subsystems change over time.

There are always ‘triggering events’ which penetrate some layers, but are generally stopped by others, until that fateful time when all of the defences are breached. This conceptual model helps us to see that the shortcomings in the defences exist without respect to whether or not there are accidents. They are a characteristic of the construction and operation of a particular subsystem or component of the system.

When referring to Reason’s diagram, note that the ‘defence’ against errors is made up of subsystems shown as layers9. In our review of medical literature to date, when the source, description, and causes of errors are given there is invariably a failure to consider the ‘layer’ representing the physical environment.

Systems and safety

It is essential that we accept the construct, which states that accidents are latent in systems and, therefore, safety is a component of systems as well as their subcomponents. Richard Cook proposed this concept in his paper, A Tale of Two Stories10. It follows that if safety is a component of the system, it might also be described as a part of the culture of the system. The IOM report, To Err is Human, describes safety as an emergent characteristic of systems11. It emerges not because one subsystem is near perfect, but because the aggregation of subsystems embodies it as a whole.

We offer this additional consideration. The challenge is to change the traditional hospital design process to incorporate the safety-driven design principles and to create or enhance the culture of safety. In planning for the new facility, we approach the hospital design process with a blank sheet of paper, an appreciation of the evidence that there is ample opportunity to improve hospital patient safety. We believe that improving hospital facility design will not only increase patient safety directly but also indirectly promote a safety-oriented organisational culture.

The new foundation for understanding human error considers that healthcare providers make mistakes because the systems, tasks and processes they work in are poorly designed. Organisational accidents have multiple causes involving many people operating at different levels. This translates into failures at the point of service (e.g. a physician ordering an allergenic drug for an allergic patient). Based on this idea, exceptional design of healthcare institutions will provide an environment of patient safety as well as a safety-oriented organisational culture. It requires a focus on safety by hospital leadership, physicians and staff that is accomplished through a continuous cycle of evaluation and improvement of the facility, equipment, technology and processes.

The traditional design concepts can be summarised as follows:

• The physical environment for healing is a shelter, but has little special interaction with the healing process or operation. The healing environment is separate, but not particularly special.

• The physical environment for healing is an ‘edifice’ or monument signifying the importance of an individual, a community or an institution.

• The physical environment for healing is an asset whose value is seen in terms of its real estate characteristics.

In contrast, we propose our concept as follows: the physical environment for healing is an integral subcomponent of the care delivery process. Like other tools and resources, its design, use and application either promote or hinder the attainment of the goals of care. These systems and subsystems or microsystems, need to be carefully designed and supported12.

The characteristics of the physical environment interact with the care process through physiological and psychological pathways. The interactions may directly or indirectly affect caregivers, patients, support personnel, equipment and operational plans.

Improving the physical environment ‘layer’ in Reason’s ‘Swiss cheese’ lies in the process by which the physical environment is created. That process has evolved over time and it now includes several variants. Our review of the characteristics of the design process, leads us to conclude they should all be considered as a single process.

Can we change the design process?

If we accept the proposition that healthcare is a system and that the physical environment is a component of that system, we might then ask whether that part of the system could be improved. In other words, is there anything wrong with the healthcare physical environment and, if so, can this layer of cheese have some of the holes filled in?

There are many deficiencies in the design of healthcare environments that contribute to adverse events. One example relates to patient falls, which is sufficiently significant to have been placed on the national list of patient safety objectives13. The design of the environment has direct and indirect impacts on patient falls and yet has been mostly ignored by regulators.

Hospitals have latitude in choosing which finish materials to use despite clear and dangerous consequences when using slippery surfaces. Why do deficiencies in the designed physical environment occur? While there has been too little peer-reviewed study of this question, the design process does have a number of characteristics, which may be at fault.

Design professionals, in the course of study for their profession, generally do not study ergonomics, human performance science, or the science of how human beings interact with their environment. An unstated conclusion of Donald Norman’s book, The Design of Everyday Things, is that designers don’t know much about everyday users3. Designers study design, not human beings. This deficiency manifests itself in the results of their work. Aside from not having a rudimentary understanding of human performance and its limitations, such as fatigue, stress and sensory degradation, designers are insulated from users. This happens because designers make assumptions about users based on their own, and not the users’, experience.

Healthcare building design projects often begin with a set of assumptions, made by the owners, the designers or others. These assumptions are not tested before or during the design process. For example, a functional programme may be created by the owner and stipulated to the designer as a given. No opportunity exists to question or test the contents of this programme or to work with clinicians and others involved in care to find better methods.

The process of design commonly used in healthcare is linear. It starts with the architect working with the givens, proceeds to a greater definition of the floor plan and massing, then adds equipment, information technology, building systems, furnishings and other components. There is a natural and financial inclination not to loop back to look at evolving issues in a holistic light.

If the plan is done, the solution must be a different piece of equipment, a different furnishing or, even worse, a process change. Likewise, after the equipment and technology are selected, usually just before construction begins, there is resistance to changing any part of the design which has been determined before.

These characteristics of the process are exacerbated by the fact that it is generally led by a single component of the design team, most frequently the architect. In alternative scenarios, the team is led by a ‘programme manager’, a ‘construction manager’ or by an ‘owner’s representative’. The problem with this form of leadership is that it tends to focus on one aspect of the project, for example, the budget, the schedule or the ‘design’, to the detriment of others.

Our search is to find methods which avoid these pitfalls, so that the resulting physical and operational environment is as safe and effective as possible (see panel box). Rather than trying to improve a process, which has demonstrably yielded inadequate results, we suggest that a new process be created.

Design for patient safety

The design process for patient safety must include three goals:

• Reduce the risk of healthcare-associated (caused by treatment) injury to patients and healthcare providers.

• Remove or minimise hazards, which increase risk of healthcare-associated injury to patients.

• Educate the design team in the complexity of designing healthcare settings for safe outcomes.

The strategy advocated for achieving these goals incorporates the following concepts14:

• Treat the creation of safety as part of a process that addresses the safety and integration of all system components, as part of the culture.

• Involve users and stakeholders at all levels of the institution in the ‘creation of safety process’ involves.

• A complete array of disciplines and knowledge is necessary at the project start.

• Use of a wide range of tools. These include: failure modes effect analysis (FMEA), root cause analysis (RCA), mock-ups, simulation, testing, and data analysis.

• Create and require team education about the patient safety problem, about the process of building design, and about the process of collaboration with others to derive effective and efficient solutions.

• Gain appreciation that designing for safety is an iterative process.

Critical Design Factors in the Physical Environment

|

| Infection Control |

• Selection of surface materials

• Handwashing station provision

• Space for maintenance of sterile technique

• Ventilation design – filtration, air flow, temperature, humidity |

| Patient Identification |

• Lighting intensity and quality

• Sound/noise – design for aural quality

|

| Surgical technique |

• Vibration

• Noise and acoustic quality

• Layout of room for:

- Placement and movement of surgical systems, robots, imaging, etc.

- Staff workflow

- Access to supplies and emergency services

• Room environment control design |

| Staff Accommodation |

• Minimise stress |

| Transfer |

• Physical – provision for patient transfer system

• Information – environment for accurate, undistracted communication

|

| Utility Systems |

• Design for ease of maintenance and indication of failure

• Clarity of controls, displays and indicators

• Standardisation of systems (important in other areas as well) |

| Systems coordination |

• Design of systems to eliminate confusing alarms and indicators

• Testing of systems in simulated surgeries to discover shortcomings |

These strategies apply to all areas of healthcare facilities. The first part of this task is to define the characteristics of the environment from the perspective of design. On top of the accommodation of new systems and procedures, patient safety teams must deal with the environments and processes surrounding those which are already in use. The building codes and regulations need to be modified to allow for these changes. Building design-related contributors to hospital-acquired infections can include: inadequate maintenance of filters; use of floor, wall or ceiling materials which are hard to clean; poor placement of hand-washing stations; insufficient space to maintain sterile separation.

Reiling wrote: “Creating a process to evaluate the interplay between equipment, technology, and facility to create safety at the beginning of the design process was challenging.”15 The process he used emphasised “focus and commitment to safety-driven design principles”.

Cultural challenges

The healthcare design process needs to be radically changed to address patient safety issues. Creating an environment in which a culture of patient safety can flourish is, however, daunting and requires a willingness to think outside the constraints of convention, and to challenge the intellectual and cultural stagnation which characterises many of our professional and commercial institutions.

Principal Authors

Paul Barach, MD, MPH is a professor at Utrecht University, Netherlands and associate professor at the University of South Florida

Kenneth N. Dickerman, ACHA, AIA, FHFI is national resource architect at Leo A Daly

Contributor

Ray Pentecost III, DrPH, AIA, ACHA is a vice president and director of healthcare architecture at Clark Nexsen Architecture & Engineering

References and Bibliography

1. Ulrich R, Quan X, Zimring C, Joseph A, Choudhary R. The role of the physical environment in the hospital of the 21st century: A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Concord CA: The Center for Health Design; 2004 Sept.

2. Sullivan LH. The tall office building artistically considered. Lippincott’s Magazine; 1896 Mar.

3. Norman DA. The design of everyday things. New York: Basic Books; 2002.

4. Leape LL.. Error in medicine. JAMA 1994. 272(23):1851-7.

5. Barach P, Johnson J. Safety by design: Understanding the dynamic complexity of redesigning care around the clinical microsystem. Qual Saf Health Care 2006; 15 (Suppl 1): i10-i16.

6. Perrow C. Normal Accidents: Living with high-risk technologies. New York: Basic Books; 1984.

7. Dickerman KN. Interdependence characteristics of systems – Chart based on Charles Perrow’s theory of complexity and coupling; 2005.

8. Reason J. Human error. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

9. Reason J, Dickerman K. Theory of mistakes, swisscheeserevenv.jpg, Editor. 2005.

10. Cook RI, Woods DD, Miller C. A tale of two stories: Contrasting views of patient safety. Chicago: National Patient Safety Foundation; 1998.

11. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To err is human: building a safer health system. Institute of Medicine report. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

12. Mohr J, Barach P. Understanding the design of health care organizations: The role of qualitative research methods. Environment & Behavior 2008; 40:191-205.

13. JCAHO. 2006 Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals. 2006.

14. Dickerman K, Nevo I, Barach P. Incorporating patient-safe design into the design guidelines. Am Inst Arch J. 2005; October:7.

15. Reiling JG, Knutzen BL, Wallen TK, McCullough S, Miller R, Chernos S. Enhancing the traditional hospital design process: a focus on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004. 30(3):115-24.

|

1.1.jpg)

|