Through Children's Eyes: Understanding how to create supportive healthcare environments for children

This study of children and adolescents in hospital identified a range of factors key to improving their experience in the healthcare environment.

Understanding children’s and young people’s experience of hospital environments and what constitutes their ideas of a supportive environment can only strengthen the capacity of designers, healthcare professionals and policy makers to create hospitals which support their needs. However the challenges of completing healthcare design research with children and adolescents in hospital environments means that not much of it exists.

|

| Outside the main entrance of The Children's Hospital at Westmead |

Over the last 15 years, participatory research with children and adolescents has been embraced by many disciplines. This is in response to the recognition that children and adolescents have critical and unique perspectives on their experience, which have the capacity to challenge adult assumptions about their lives and to ground them in the reality of children’s lives1.

This paper discusses a participatory qualitative case study, completed with children and adolescents in a children’s hospital in Sydney, Australia. The participants involved in the study were aged between nine and 18 years and had been resident in the hospital for at least seven days.

The aims of the research were firstly to understand what constitutes a supportive paediatric setting from children and adolescents’ perspectives; secondly, to describe the roles of the physical environment in children’s feeling of wellbeing; and thirdly, to illustrate the value of participatory research to healthcare design.

The findings from this study indicate that children and adolescents seek to actively manage, negotiate and cope with their time in hospital. They value an interactive, engaging and aesthetically pleasing environment and a friendly, caring welcome from the hospital community. Children’s and adolescents’ assessment of the appropriateness of the environment is linked to the aesthetics of the environment, the volume of age-appropriate activities there are available within the hospital and the friendliness and welcome they receive from the hospital community.

|

| Wards overlooking the children's garden |

Their feeling of wellbeing in hospital is dependent on their capacity to remain engaged, maintain a positive frame of mind and to feel comfortable in the hospital setting. The concept of person-environment fit for children in a hospital setting, which emerges from this study, is a dynamic interaction between patients and their environment which is influenced by the patient’s individual circumstances and the amount of time they spend in the environment2,3.

Supporting children’s experience of fit in a hospital setting means being mindful of the need to support children’s choices, needs and purposes and their capacity for self-help4. In particular, a supportive environment should not resist children’s efforts at self-help and should recognise the dynamic cycles of mutual influence between patient and environment that underpin children’s struggle for their feeling of wellbeing in hospital.

The key physical attributes identified in this study include aesthetics (colour, artwork and brightness), spatial variety (in particular the function and variety of non-medical spaces) and, thirdly, the value participants gave to adaptability and flexibility in the environment.

Supportive hospital environment

As stated, research with children and adolescents in hospital environments is limited. It provides an incomplete patchwork of considerations relevant to children’s experience of hospitalisation. However, the evidence that exists on children’s experience of hospitalisation is formative, identifying aspects of the experience that children and adolescents consider supportive in a healthcare context.

|

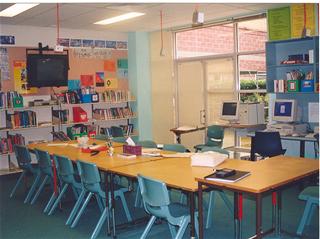

|

The book bunker combines a learning opportunity with social interaction

|

From the earliest research on children’s experience of hospitalisation, or with children and adolescents in hospital environments, there have been a number of persistent themes. Early research revealed that personal considerations include the need to provide opportunities for self-care management, confidentiality, competence, control and choice5-7.

Social considerations include the need for social support and social contact with friends and families5,6. Organisational considerations involve the need to provide adequate cognitive stimulation, and access to recreational and learning activities5-7. Physical environmental considerations include the need for personal space, privacy, independent movement and comfort within the environment5-7.

More recent research has supplemented these findings and added further considerations for all domains including physical environmental considerations, such as the need for age-appropriate spaces and interiors, especially for adolescents8-14; respecting the importance of having personal possessions for patients and being able to

personalise their bed area8,15; identifying a preference for colour and artwork in the environment8,16,17; and identifying the importance of having access to gardens in the hospital environment18-20.

Social considerations such as understanding the importance of having access to school13,21; understanding the importance of good provision for families and their needs21-23; and the need for active support, professionalism, respect and friendliness from staff21,22 have also been established in recent research.

|

| A treatment room in the Children's Hospital at Westmead |

Organisational considerations include the need for the provision of age-appropriate activities, especially for adolescents8-14; and the need for information that supports children’s and adolescents’ understanding of their own situation and their capacity to participate in their own healthcare management21,22,25,26. Food and its quality, variation, and choice were also important considerations for adolescents8,9.

There are three notable limitations of current research into children’s and adolescents’ experience of hospitalisation. The first is that the current understanding does not provide a holistic picture of their experience; secondly, many of the findings do not supplement the identification of an important attribute within children’s and adolescents’ experience with an understanding of why it is important and what role it is playing; and thirdly, not all of these studies were completed with children and adolescents who were in, or had experienced, a hospital environment.

To be able to assemble the key attributes in a hospital environment effectively, there has to be a greater understanding from children themselves of how they use them and what for. To reach this understanding, research needs to be carried out with children and adolescents in the context of healthcare environments, or with those who have experienced hospital settings.

|

| The Starlight Express room enhances spatial variety at the hospital |

Research design and methods

Our study consisted of a single qualitative case study. Qualitative research offers children and adolescents an opportunity for them to give direct accounts of their experience and reveal their competence as critics and commentators on their own lives27-34.

The case centred on the experience of longer-term patients in a modern paediatric hospital – The Children’s Hospital at Westmead in Sydney, Australia. Participants had to have been admitted to the hospital for at least seven days at the time they were interviewed. The study was completed in four stages involving 55 children and adolescents aged 7-18 years; 41 of these were patients in the hospital and 14 participated in a pilot study completed with children and adolescents who were not patients. Twenty-four of the 55 participants were involved in pilot studies, including nine boys aged 7-16 years and 15 girls aged 7-18 years. Thirty-one participants were involved in the main study, including 13 boys aged 9-17 years and 18 girls aged 10-18 years.

Stage one consisted of a series of pilot studies designed to refine the questions for research and methods of data collection. This stage provided children and adolescents with the opportunity to shape the development of the study and the methods used.

Stage two consisted of the data collection phase for the main study. Children and adolescents were asked to complete a single interview which consisted of three tasks. Task A included an informal discussion centred on a set of photographs of the hospital environment taken by participants in the second pilot study. Task B involved answering a set of 30 questions spanning the possible domains and dimensions of children’s experience of hospitalisation and wellbeing derived from both the literature and the findings from the pilot studies. Task C involved a game task which functioned as a consistency check within each interview.

|

The Chinese gardens combine access to outdoor spaces with cultural learnings

|

Stage three involved the analysis of the data. The interviews resulted in three sets of data, including two sets of narrative data from tasks A and B which were analysed using concept mapping35 and thematic analysis techniques36-40, and the game task results which required tallying. The results from each of the three data sets were triangulated to create preliminary findings.

These were then taken back to a group of six patients who were representative of the profile of participants in the main study as part of a member-checking exercise, before stage four, when conclusions were finalised.

Research findings

A supportive paediatric environment: The findings from this study provided a preliminary defi nition of a supportive paediatric environment which includes:

• an environment that supports children’s feelings of wellbeing by addressing their need to feel comfortable in the environment, maintain a positive frame of mind and remain positively engaged;

• an environment that facilitates children’s goodness of fit by supporting individual choice, control and self-help and by minimising unwanted distractions (such as noise, light and unsolicited social contact); and

• an environment that maximises the opportunities to include features which are identified by the study as indicating child-friendliness. These include maximising the volume of age-appropriate activities in the environment, and providing a bright and colourful environment and a welcoming and friendly social environment.

Children’s feeling of wellbeing in hospital: The study also revealed that the concept of feeling of wellbeing is a subjective and fluctuating self-assessment that encompasses three principal components:

• children’s capacity to feel comfortable in the environment where comfort is understood to be comprised of physical, social and emotional considerations;

• children’s capacity to maintain a positive frame of mind that encompasses their capacity to minimise the impact of difficulty and boredom, and maximise the opportunity of having positive and entertaining experiences; and

• children’s capacity to remain positively engaged, which encompasses children’s active involvement and participation in their experience of hospitalisation, enabling them to exert control and to experience competence and empowerment.

|

| Art project: Butterfly installation |

Participatory research and healthcare design: Participatory research with children and adolescents in healthcare environments challenges the way children and young people are conceptualised and therefore the way they may be accommodated in design.

This study indicates that children and adolescents should be conceptualised as active shapers, managers and negotiators of their experience in hospital which is in keeping with the sociological conceptualisation of children as social agents in their own lives41.

This breaks from a more traditional conceptualisation of patients as passive recipients of care at the mercy of stressful, overbearing healthcare environments. The conceptualisation that emerged in this study encompasses children’s preference for inclusion and participation in all aspects of their experience and their expectation of active self-management as far as possible. In particular participatory research challenges adult assumptions about children’s lives and challenges adult’s depictions of them. This in turn will challenge the way they conceive of accommodating children and adolescents within any design. It also has the capacity to ground adult understanding in the reality of children’s experience rather than the imagined reality of children’s experience. This identifies the importance of completing research with children and adolescents in the contexts in which their experience is taking place.

A specific example of how information from children and young people themselves may challenge trends in healthcare design, if they were allowed to, concerns the configuration of ward rooms. Currently there is an increasing trend to support the design of wards which consist entirely of single rooms.

This is driven largely by a medical agenda to improve infection control, although this is not well substantiated in research at present42. In this study, half of the sample preferred single rooms and half preferred shared rooms.

Sharing was preferred by participants because it provided company and prevented them from being alone and feeling lonely. Shared rooms consisting of two people were considered the optimum. Single rooms were preferred because they gave the participant control over the social contact they would have with other patients, as well as more privacy with their families. In light of the current trend for single rooms, the experience of a modern hospital for many of the participants in this study would be without the social support and contact that they need and it may even give rise to new fears of being alone. If children’s views on this subject and children’s holistic needs were allowed to infl uence the final design preference and solution adopted, a very different design trend may be advocated.

|

| Example of a personalised bed area |

Design recommendations

This study sought to identify attributes of the physical environment that were involved in children’s and adolescents’ feeling of wellbeing in a hospital environment. The three main design recommendations that resulted from this study include environmental aesthetics, spatial variety and the need for adaptability and flexibility in the environment.

The roles of environmental aesthetics: The environmental aesthetic features that children and adolescents discussed in this study included artwork, colour and brightness. Through these three aesthetic elements, children and adolescents perceive messages of welcome, comfort, appropriateness and fun. In combination, these three elements help children and adolescents to sustain a positive frame of mind and to remain positively engaged, both of which directly contribute to their feeling of wellbeing. The key features in relation to each of the three elements include:

• Artwork: art should be age-appropriate and without the simplistic images associated with young children. It should include artwork completed by other children and adolescents, as this artwork in particular conveyed messages of support and welcome and the importance of children’s welfare to the organisation.

• Colour: the environment should include a large amount of colour – preferably bright colour – and this should vary around the environment.

• Brightness: brightness is a nebulous concept that represents a composite assessment of a range of environmental features, potentially involving many different aspects of the environment, including the need for a lot of colour, artwork, light and plants in the environment. Anything in the environment can contribute to the assessment of brightness, ranging from the social attitudes of the hospital community to the colour of carpet and furniture, and the size and placement of windows and skylights.

|

School room at The Children's Hospital in Westmead

|

The importance of spatial variety and function: Spatial variety encompasses the need for non-medical places and spaces offering a range of different activities, atmospheres and spatial qualities, including outdoor and natural areas. This spatial variation plays a key role in enabling patients to meet their needs for environmental contrast, emotional self-regulation and self-restoration and to exercise control and self-management. Specifically, these recommendations include:

• providing facilities which enable children and adolescents to carry out normal routines with their friends and family, such as cafes, shops, common room areas, play areas and age-appropriate areas for socialising (particularly for adolescents); and

• providing access to outdoor areas and natural environments for contrast and to enable patients to escape and to experience a restorative environment. ‘Natural’ green places (gardens, in this study) are preferred areas and play a key role in patients’ emotional self-regulation and self-restoration and their ability to access privacy, as well as providing greatly appreciated environmental contrast with the indoor environment of the hospital.

The value of flexibility and adaptability

Providing flexible and adaptable environments or environmental attributes means providing patients with the capacity to alter their immediate environment. This translates into providing patients with the capacity to experience control, express their identity and reveal their interests, to alter the environment aesthetically and to personalise it with familiar and valued objects.

Being able to personalise their bed area was the best representation of this in this study. The value in being able to do this for patients is in their capacity to feel more comfortable in the environment and less removed from their lives outside of hospital. It also reduces the strangeness of the environment and the experience of hospitalisation. Any opportunity to increase the capacity for patients to manipulate their environment in a hospital design would be appreciated by children and adolescents.

Conclusion

The findings reveal that children’s and adolescents’ experience of the paediatric setting involves a number of major areas of influence including their personal situation, their social experience, their interaction with the physical environment, the opportunities and characteristics of the organisation, and the effect of time.

The findings also reveal that children’s feeling of wellbeing within this experience is linked to their ability to feel comfortable in the environment, to maintain a positive state of mind and to remain positively engaged with the experience and the environment.

Children and adolescents reveal that they are active shapers, managers and negotiators of their time in hospital. Completing research in a healthcare context is difficult. However, it is only through children’s and adolescents’ participation in research and design processes that we can be sure that we have identified the specific considerations which are formative in their experience as patients. We should not be designing paediatric healthcare settings that do not reflect evidence from children’s and adolescents’ lived experience of hospital environments.

Participatory research with children and young people can provide rich insight into their experience of a paediatric hospital setting which can only enrich our understanding and our capacity to provide hospital environments that support their needs.

Author

Kate Bishop PhD is an Australian researcher and design consultant specialising in children, youth and environments. The full thesis is available online and can be downloaded from the Australian Digital Thesis database at http://hdl.

handle.net/2123/3962

References

1. Graue ME, Walsh DJ. Studying children in context: Theories, methods, and ethics. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 1998.

2. Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining health environments: Toward a social ecology of healthy promotion. American Psychologist 1992; 47(10):6-22.

3. Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion 1996; 10(4):282-298.

4. Kaplan R. A model of person-environment compatibility. Environment and Behavior 1983; 15(3):311-332.

5. Lindheim R, Glaser H, Coffi n C. Changing hospital environments for children. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 1972.

6. Olds AR. With children in mind: Novel approaches to waiting area and playroom design. Journal of Healthcare Interior Design 1991; 3:111-122.

7. Rivlin LG, Wolfe M. Institutional settings in children’s lives. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1985.

8. Blumberg R, Devlin AS. Design issues in hospitals: The adolescent client. Environment and Behavior 2006; 38(3):293-317.

9. Carney T, Murphy S, McClure J, Bishop E, Kerr C, Parker J et al. Children’s views of hospitalization: An exploratory study of data collection. Journal of Child Health Care 2003; 7(1):27-40.

10. Hutton A. The private adolescent: Privacy needs of adolescents in hospitals. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2002; 17(1):67-72.

11. Hutton A. Activities in the adolescent ward environment. Contemporary Nursing 2003; 14(3):312-319.

12. Hutton A. Consumer perspectives in adolescent ward design. Issues in Clinical Nursing 2005; 14:537-545.

13. Kari JA, Donovan C, Li J, Taylor B. Teenagers in hospital: What do they want? Nursing Standard 1999; 13(23):49-51.

14. Tivorsak TL, Britto MY, Klosterman BK, Nebrig DM, Slap GB. Are pediatric practice settings adolescent friendly? An exploration of attitudes and preferences. Clinical Pediatrics 2004; 43(1):55-61.

15. Shepley MM, Fournier MA, McDougal KW. Healthcare environments for children and their families. Dubuque IA: Association for the Care of Children’s Health; 1998.

16. Coad J, Coad N. Children and young people’s preference of thematic design and colour for their hospital environment. Journal of Child Health Care 2008; 12(1):33-48.

17. Sharma S, Finlay F. Adolescent facilities: The potential...adolescents’ views were invited in the planning of a new unit, but to what extent were their suggestions incorporated? Paediatric Nursing 2003; 15(7):25-28.

18. Sherman SA, Shepley MM, Varni JW. Children’s environments and health related quality of life: Evidence informing pediatric healthcare environment design. Children, Youth and Environments 2005; 15(1):186-223.

19. Sherman SA, Varni JW, Ulrich RS, Malcarne VL. Post occupancy evaluation of healing gardens in a pediatric cancer center. Landscape and Urban Planning 2005; 73:167-183.

20. Whitehouse S, Varni JW, Seid M, Cooper Marcus C, Ensberg MJ, Jacobs JR et al. Evaluating a children’s hospital garden environment: Utilization and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2001 21:301-314.

21. Liabo K, Curtis K, Jenkins N, Roberts H, Jaguz S, McNeish D. Healthy futures: A consultation with children and young people in Camden and Islington about their health services. London: Camden & Islington NHS Health Authority; 2002.

22. Hall JH. Child health care facilities. Journal of Healthcare Interior Design 1990; 11:65-70.

23. Hopia H, Tomlinson PS, Paavilainen E, Aestedt-Kurki P. Child in hospital: Family experiences and expectation of how nurses can promote family heath. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2005; 14:212-222.

24. Moules T (Ed). Whose quality is it? Young people report on a participatory research project to explore the involvement of children in monitoring quality of care in hospital. Paediatric Nursing 2004; 6(6):30-31.

25. Hallstrom I, Elander G. Decision-making during hospitalization: Parents’ and children’s involvement. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2004; 13:367-375.

26. Smith L, Callery P. Children’s accounts of their preoperative information needs. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2005; 14:230-238.

27. Christensen P, James A. Research with children: Perspectives and practices. London: Falmer Press; 2000.

28. Fraser S, Lewis V, Ding S, Kellett M, Robinson C. Doing research with children and young people. London: Sage; 2004.

29. Kellett M. Just teach us the skills please, we’ll do the rest: Empowering ten year olds as active researchers. Children & Society 2004; 18:329-343.

30. Kellett M. Children as active researchers: A new research paradigm for the 21st century? London: ESRC National Centre for Research Methods; 2005.

31. Lewis A, Lindsay G. Researching children’s perspectives. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 2000.

32. Mayall B. Children’s childhoods observed and experienced. London: Falmer Press; 1994.

33. James A, Prout A. Constructing and reconstructing childhood. London: Falmer Press; 1997.

34. Qvortrup J. Macroanalysis of childhood. In P. Christensen & A. James (Eds), Research with children: Perspectives and practices (pp77-97). London: Falmer Press; 2000.

35. Jackson KM, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping as an alternative approach for the analysis of open-ended survey responses. Organizational Research Methods 2002; 5(4):307-336.

36. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic enquiry. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 1985.

37. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: A source book of new methods (2nd ed). Beverley Hills CA: Sage; 1994.

38. Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field methods 2003; 15(1):85-109.

39. Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park CA: Sage; 1990.

40. Weller SC, Romney AK. Systematic data collection. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988.

41. Prout A, James A. A new paradigm for the sociology of childhood? Provenance, promise and problems. In A James & A Prout (Eds), Constructing and reconstructing childhood. London: Falmer Press; 1997.

42. Dowdeswell B, Erskine J, Heasman M. Hospital ward configuration: Determinants influencing single room provision. UK: European Health Property Network for NHS Estates; 2004.

|

1.1.jpg)

|