The effect on mood of a 'living' work environment

Research suggests that nature can have a positive effect on mood, but which aspects have the greatest influence? This study investigates the link between the living component of nature (as opposed to artificial nature) and restorative potential

Chloe Hamman, MA Science (Hons) BCA; Dr Linda Jones

In many cultures, both past and present, behaviour reflects a positive engagement with nature; from the ancient Greeks’ custom of protecting their sacred gardens, to the native American animistic practice of giving thanks to the trees, a preference for the world of nature has long been expressed through ritual, art and myth.1

An investigation of city landscape planning for urban green spaces found that in a population of city dwellers more than 70% of residents wished they could visit ‘nature’ and green spaces more often than they did.2 Moreover, people tend to show an overwhelming preference for natural environments over man-made and often perceive natural scenes as more beautiful than artificial environments.3,4

The biophilia hypothesis

The evolutionary psychologist EO Wilson asserted that there is a genetic basis to human beings’ “ubiquitous fondness for nature,”4 a phenomenon he named the ‘biophilia hypothesis’. Kellert and Wilson declared this inherent preference for nature to be a result of our evolutionary history.5 Since we went through years of living and depending on nature for survival, we developed an innate emotional affiliation with other organisms, such that contact with nature became a basic human need.6

According to the biophilia hypothesis, the reason people favour nature over man-made objects may result from an innate belief that exposure to nature can foster wellbeing and bring about positive changes in cognition and emotion.6 Regan and Horn3 addressed preferences for nature in relation to mood states and found that people exhibited a desire for being around nature when relaxed, suggesting people may have a belief that exposure to nature is a good way to remain in a relaxed state. Is there functional benefit to our apparent preference for nature? Biophilia has become a scientific field of research that explores this very question and considers the human connection to nature and how the latter can improve our health and wellbeing.

Research on the restorative benefits of nature

A growing amount of research supports the idea that exposure to nature can be beneficial for one’s health in creating a restorative environment.7,8,9,10,11 By definition, restorative environments are those which can help reduce emotional stress and increase wellbeing.12

Grahn and Stigsdotter2 found that the more time people spend outdoors in urban green spaces, the less they are affected by stress. Ulrich10 found that patients with views of nature had shorter hospital stays overall, required less pain medication and received fewer negative evaluative comments from their nurses. A prison study found that inmates with outer-facing cells with views of vegetation and landscape recorded fewer days at the health clinic than those with inner-facing cells.13 However, green nature (ie trees and plants) is not the only form of nature that can bring about positive restoration. Exposure to animals can also foster psychological wellbeing in terms of reducing signs of stress and promoting happiness,8,14 as well as inducing feelings of calm and relaxation.15,16,17

Theoretical frameworks

Research into the effects of the restorative effects of nature tend to employ either of the following theoretical standpoints: attention restoration,18 or stress recovery.11

Attention restoration theory (ART) focuses on cognitive processes and suggests that nature creates a restorative environment for our brains to recover from the demands of daily mental activity.2 ART suggests that because nature requires very little attention to be sorted and assessed it attracts involuntary attention, or ‘soft fascination’. Therefore, when viewing nature our higher cognitive function rests while soft fascination takes over and more primitive parts of our brain are stimulated.18

Stress-recovery theory focuses on human evolutionary adaptation, in respect of our positive response to nature,19 to understand the physiological and emotional changes that occur in the presence of nature. Exposure to natural elements, such as plants and water – potentially associated with sustenance and safety – may send a positive signal to suggest that the body can relax and recover from stress. It is through this process that viewing nature is said to be able to provide a restful experience and to have a positive physiological and psychological impact.1

It has been empirically demonstrated that exposure to nature can be restorative for health, in terms of better recovery.12 This recognition is reflected in many hospitals having therapeutic gardens for patients20 and the widespread implementation of animal-assisted therapy.17 Furthermore, many nursing homes have either residential animals or animal visitation schemes as part of an overall recreation programme.16

Nature in the workplace

Even though most adults spend a greater part of their day at work, very little attention has been devoted to the role of nature in the workplace.21 The majority of research has instead been carried out in therapeutic settings, hospitals or prisons. What research has been carried out in work environments supports the idea that exposure to nature can have positive implications for employee wellbeing and job satisfaction. Nature in the workplace may reduce stress,22 decrease sick days and improve mood and job satisfaction,23 increase productivity,24 and even stimulate creativity.25 One study carried out in a workplace setting showed that offices allowing employees access to views of nature resulted in fewer worker reports of headaches and illnesses.26 Another study found that feelings of stress and anger decreased the most when nature content was present in art posters decorating an office.22

Artificial versus living nature

Grinde and Patil,7 whose 2009 review explored the restorative potential of exposure to nature, concluded that nature appeared to offer qualities useful for stress relief and mental restoration, thereby improving mood. What remained inconclusive was which aspects of nature were responsible for the positive effects found in the 50-plus empirical papers reviewed. Were the restorative benefits of nature due to the aesthetic qualities of stimuli – visual features, such as colour or shape? Were the benefits dependent on nature’s organic characteristics? The core premise of biophilia is that people have a genetic predisposition to react to biological phenomena, suggesting that the ‘living’ component of nature stimuli is what is inherently valued and restorative.22 Given that, particularly in the workplace, the nature stimuli are mere artificial representations (eg artificial plants, nature screensavers), it is important to determine if these are suitable substitutes for living nature in relation to restorative potential.

Most studies exploring the ‘living’ aspect of nature have only compared living nature stimuli (eg plants and fish) with artificial non nature-related stimuli (eg art or posters). There are, however, some exceptions. A study by Katcher, Segal, and Beck28 found that viewing living fish in an aquarium reduced anxiety and discomfort during dental surgery compared with viewing a picture of a waterfall nature scene. In contrast, DeSchriver and Riddick14 found that living nature is not always better than simulations of nature in terms of restoration. Their study comprised three groups of elderly participants – one gazing at an aquarium of live fish, one gazing at a video of the same, and a control group. The group viewing the video showed the lowest physiological signs of stress. Although these results could be due to the fact that watching videos is a similar activity to watching TV, a favourite pastime of the participants, DeSchriver and Riddick concluded that a nature stimuli “need not be animate” in order to evoke a positive response.14

In another study, by Friedman, Freier, Kahn, Lin and Sodeman,29 the restorative qualities of viewing real nature versus artificial nature were explored in a workplace. Participants were assigned to one of three conditions: a glass window with a view to nature, a plasma screen with a high-definition view of the same setting, or a curtained wall. Heart-rate recovery measurements suggested the view to real nature provided significantly more restorative qualities than both the plasma screen and the curtained wall.

Another study explored differences in the psychological impact of real and artificial plants and flowers.30 Researchers decorated tables with either cut (real) flowers and plants or artificial versions and asked participants to evaluate the tables. Artificial and cut plants triggered evaluations based on similar adjectives related to aesthetic pleasantness, such as ‘colourful’ and ‘bright’; however, the cut flowers showed significantly more evaluations related to positive mood conditions, such as pleasantness and relaxation. Shibata and Suzuki also found a significant difference between self-reports of positive mood when exposed to real plant conditions compared with artificial plant conditions.31

|

|

Figure 1: Nature stimuli used for living plant condition

|

Figure 2: Nature stimuli used for artifical plant condition

|

The latest study

The objective of this latest study was twofold. Firstly, it aimed to replicate previous findings that suggest viewing nature can have a positive effect on mood. Secondly, it aimed to explore whether or not living nature stimuli are superior to artificial ones in terms of restorative potential.

Based on findings from previous research, it was hypothesised that: participants would report higher levels of positive mood during the nature stimuli conditions (both live and artificial) as compared with the control (no nature) condition; and that participants would report higher levels of positive mood during exposure to living nature (live plant and live fish) as compared with exposure to artificial nature (fake plant and fish screen).

Six female employees at a New Zealand high school participated. They worked separately in adjacent offices, in administrative roles. The four conditions of living nature stimuli and the control condition formed the independent variables. In the living plant condition the environmental stimulus was a potted, living green plant (Figure 1). In the artificial plant condition it was a potted, artificial green plant (Figure 2), of similar size to the living plant. In the living fish condition (Figure 3), the environmental stimuli was a 20-litre-capacity glass aquarium holding two live goldfish, with rocks, but no aquatic plants. The artificial fish condition was an illuminated screen playing a moving image of a similar-sized aquarium with many fish (Figure 4). In the simulated conditions (artificial plant and artificial fish) the stimuli were selected to represent as close a match to the living version as possible.

|

-condition.jpg) |

Figure 3: Nature stimuli used for living fish condition

|

Figure 4: Nature stimuli used for artifical fish (screen) condition

|

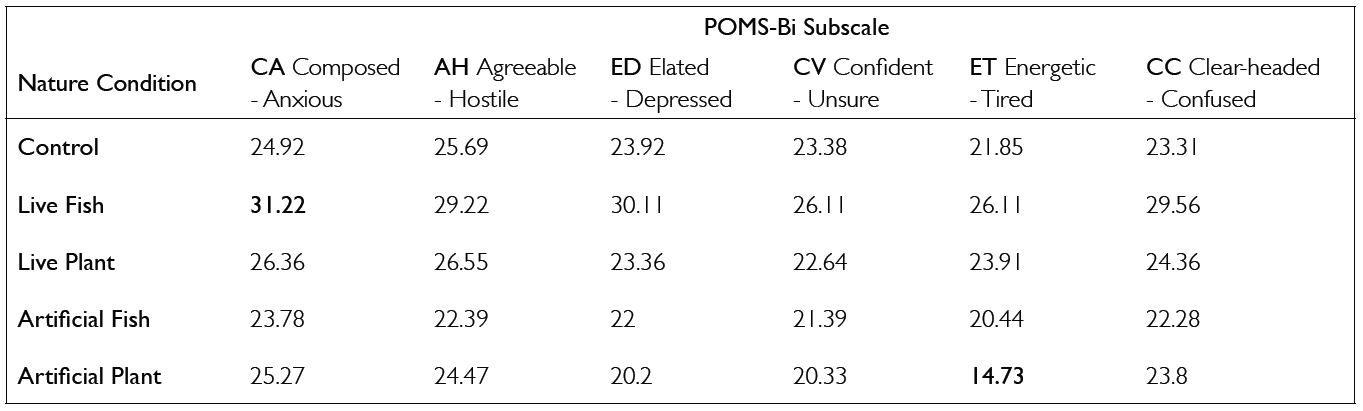

The dependent variable was participants’ mood state. Mood scores were collected daily using an adapted version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-Bi) (Bi-polar version).32 The POMS-Bi is a 72-item questionnaire with subscales covering six mood dimensions: composed-anxious (CA), agreeable-hostile (AH), elated-depressed (ED), confident-unsure (CV), energetic-tired (ET), and clear-headed-confused (CC). The questionnaire, titled ‘How did you feel today?’, uses a four-point Likert scale (zero to three) with responses to the above mood dimensions ranging from “much unlike this” to “much like this”. On all subscales a higher score reflects a more positive mood. An optional section was provided for additional comments.

A small-N study was conducted over a period of five weeks in participants’ own offices. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four nature stimuli conditions, or the control condition – ie their office, with no added item. They were told that they would have a different item introduced into their office in four of the five weeks. Participants arrived at work each Monday during the study to find one of the nature items placed in a clearly visible location – which remained constant for each item – or no item if they were in the control condition that week. Completed daily questionnaires were collected at week end and, at the end of the fifth stage (week five), the researcher carried out a brief semi-structured interview with each participant to record their perceptions and experiences of participation.

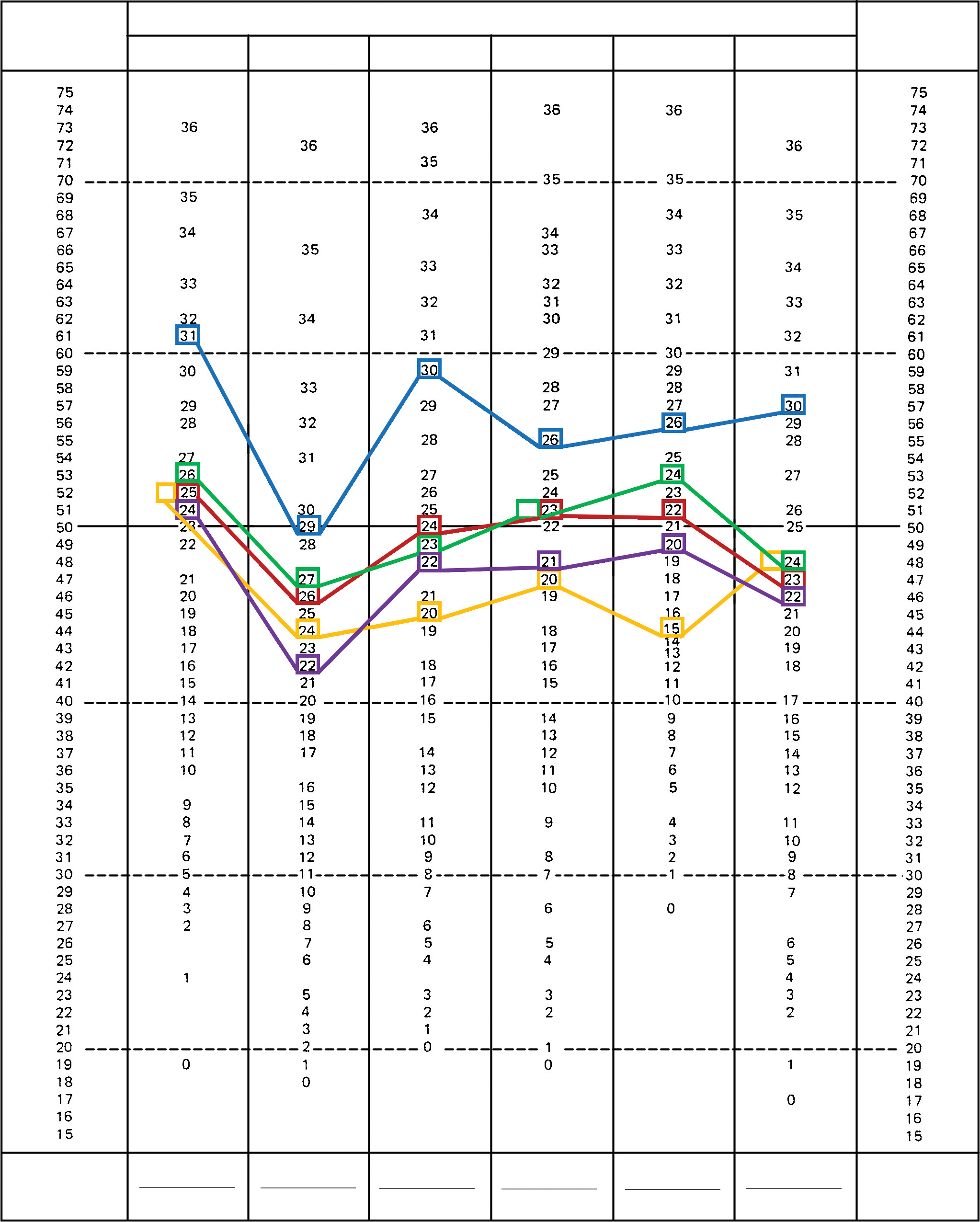

Quantitative analysis of the mood scores converted raw data for the 72 items to t-scores for each nature-condition. Participants’ daily mood was plotted and compared with published norms. The overall group-norm profile for the six subscales across the five conditions are presented in Figure 10. Group profiles were derived from the information presented in Table 1, which reports the mean data for participants’ scores on the POMS-Bi subscales across each condition. The subscale scores of 31.22 and 14.73 in bold indicate the range of mood scores obtained.

The scores for the living fish condition were the highest across all six subscales (see Figure 5), with the CA subscale being the highest overall (mean score (m)=31, t=61). The t-scores for the artificial fish conditions were below the norm on five of the six subscales and below the control condition on every subscale, with the lowest being on AH (m=22, t=42). The control subscale scores formed a baseline measure for the group. In the control condition, the group scored close to the norm-group mean across the six subscales.

Participants showed definite fluctuations in subscale scores across the five conditions, although there were no extreme scores to distort the group score for one particular subscale or condition. The control-condition scores were generally all in the mid-range.

Qualitative evaluations elicited from the participants revealed an overall sentiment that the presence of living fish in their office was a beneficial and enjoyable experience. Indicative of this are such comments as “The fish made my day”; “I think every school should have fish”; and “They [fish] have a calming effect on one’s mind.” Moreover, at the conclusion of the study, a number of participants expressed their disappointment when the fish were removed. Such positive comments were not made in reference to any of the other items.

|

|

Table 1: POMS-Bi subscale mean group scores across nature conditions

|

|

|

|

| Figure 5: POMS-Bi group profile for fish and plant conditions |

|

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effects on mood of viewing nature in a work environment, and if any effects found might differ depending on whether the nature stimuli are living or artificial. Predicting that all four nature stimuli would bring about positive changes in mood relative to the control, the artificial fish condition was, in fact, below the control on all subscales.

The second hypothesis – that living nature would elicit higher mood scores than artificial nature – was supported. Mood scores were more positive for both of the living nature conditions compared with the artificial conditions. The living fish condition resulted in the highest positive mood overall. Qualitative evaluations further indicated a preference for the living fish over the other nature stimuli.

These results provide preliminary evidence that living nature can offer greater restorative potential in terms of mood improvement than an artificial equivalent. In line with these findings, Adachi, Takano, and Kendle30 found that while artificial nature may be aesthetically pleasing, it may be inadequate in terms of “biophilia compatibility”. In the latest study, it is possible that the artificial nature conditions had less of a positive effect on mood, as participants could not experience the same feelings of comfort and relaxation as they did when exposed to the living nature.

In accordance with the biophilia hypothesis, it is possible that if we know something is alive then our attention is drawn to it. This theory provides one possible explanation for why participants reported more negative moods when the artificial nature stimuli were present in their office compared with the other conditions – a finding that could have resulted from participants’ awareness of the artificiality of the stimuli. In a study addressing the effects on mood of real versus artificial plants, Shibatu and Susuki31 found that participants who thought that plants were real had higher mood scores than those who thought they were artificial. These researchers suggested that the positive influence of nature may not be caused by actually looking at living nature, but instead by the belief that looking at living nature has a restorative effect.

In the present study, it was obvious that the artificial plant and the fish on the screen were not alive. As such, mood evaluations during the artificial conditions may have been influenced not by the fact that the stimuli were artificial but by participants’ knowledge of their artificiality. It would be interesting for future research to explore whether awareness alone of stimuli’s artificiality influences mood evaluations.

Participants’ moods were most positive during exposure to the living fish, with scores in this condition being the highest overall on the six subscales. Furthermore, qualitative evaluations elicited from participants during the live fish condition support the conclusion that participants also had a preference for the living fish over the other nature conditions.

These findings suggest that living fish offer greater restorative potential than representations of nature. As mentioned above, Katcher et al.28 found that viewing a real aquarium was superior to viewing a picture of nature, in relation to reducing stress and discomfort in dental patients. Proposing that the complexity of a stimulus is a key determinant of its restorative potential, Katcher et al. concluded that the reason the living fish in their study were able to provide a greater source of positive distraction was because they were visually more complex than the poster representation of nature. In the latest study, the fish aquarium was also visually more complex and detailed than its artificial equivalent. Linking the current results to Attention Restoration Theory (ART), the complexity of the fish aquarium may have been a greater source of fascination for participants than that of the fish screen, and it therefore provided more opportunity for distraction away from negative moods.26 If the relative complexity of a stimulus is what determines its restorative potential, then it may be the case that a sufficiently complex and detailed representation of nature could equal living nature in terms of providing restoration. The issue of complexity and restorative potential is worth exploring in future research.

The dynamic movement of the real fish may also be what led to the positive impact on mood and may also account for the apparent less positive impact of the live plant. Friedman et al.,29 who, as noted above, found that a view of real nature surpassed a high-definition plasma screen of the same view, in terms of physiological recovery, also highlighted the importance of dynamic nature, such as moving water and trees swaying in the wind. According to Friedman et al, movement in nature evokes all the senses, not just visual stimulation; it is this sensory interaction with life that we thrive on.

The noted positive effect on mood while exposed to the living fish condition can possibly be explained by theories of social research.32 Animals have been described as “social catalysts” in the way they encourage social interaction among people.33 According to Beck and Katcher,34 companion animals, such as fish, birds, and dogs, provide social support by acting as facilitators of social interactions between people. They can become conversation points by providing a common ground for discussion with others. Animals have also been shown to make social interactions more positive, which, in turn, can bring about more positive mood experiences, such as joy and humour.16

In a workplace environment, negative interactions with co-workers can create feelings of irritability, tension and frustration. A study found that on days in which interactions with co-workers were described as negative, participants also reported more negative moods.35

Given that participants in this study work in an environment where social contact is a frequent and necessary part of the job, such interactions will no doubt affect their daily moods. If the living fish in this study were able to make these social interactions more pleasant, then this provides a plausible explanation for how the living fish may have inadvertently had a positive effect on mood. This theory that social interactions at work could be made more pleasant by introducing living animals is an area worth exploring in future studies.

In contrast to much previous research, the current study found that the live plant made little difference to participants’ moods. While the work of Larsen et al.23 also indicates that a single plant in an office has little effect on mood, they did discover that mood was positively related to plant density. So, as the number of plants in an office increased, so did positive mood evaluations. Such findings suggest that the single plant used in this study may have been insufficient to provide a restorative environment for participants. Nature stimuli density and restoration are also worth exploring in future research.

|

|

Figure 6: Nature in the workplace can have a positive impact on wellbeing

|

Figure 7: Living nature was found to improve mood more than artificial nature

|

Limitations and implications

There are a few limitations to this study that should be noted. Stress levels in participants prior to the study may have impacted the results. Studies have shown that the effects of nature are greater for those who have relatively high levels of stress, and the restorative benefits of nature could be less potent if participants have moderate restoration needs.36

In addition to existing stress levels, there are numerous other workplace factors that may have influenced mood evaluations. A worker’s individual characteristics, too, can affect their attitude and mood.37 While this study may have been more reflective of what actually occurs in the workplace, it lacked much of the control of confounding variables often exercised in a laboratory setting. With these factors in mind, future research could attempt to replicate these preliminary findings while minimising potential confounds, by setting controls for both participant state and trait characteristics.

The small sample size of this investigation is another limitation. The small-N design was chosen because the study required a fairly lengthy exposure to the nature stimuli, plus it was deemed most feasible to meet time and resource constraints. Nonetheless, hopefully this study has sparked interest for future research to explore the biophilia hypothesis in a sample large enough to determine if statistically significant differences in mood can be identified among the various nature conditions.

In spite of these limitations, the results of this study suggest that living nature can have a positive effect on mood in the workplace. Such findings have implications for managing stress and wellbeing at work. Positive emotional states may predict factors such as job satisfaction and wellbeing, whereas negative ones may have a stronger relationship with undesirable workplace outcomes, such as stress.38

In New Zealand, organisations are required by law to play an active role in managing workplace stress. Part of this role involves taking practical steps to ensure that the workplace environment supports employees’ wellbeing and helps prevent unnecessary stress.39 Current findings indicate that something as simple as adding a piece of living nature to an office environment could have positive effects on mood, and therefore help reduce some of the negative consequences associated with stress. If the results of this study were to be applied to the workplace, the stimulus likely to provide the most positive benefit would be an aquarium with living fish.

The results of this study also suggest that substitutes for nature may be inadequate in providing a restorative environment. With the growth of technology-based artefacts in our modern society, it is important to consider the implications of this study when designing a work environment to maximise the benefit to its occupants. The reality is that in some workplaces it may not be feasible to bring living nature inside (eg in sterile laboratories). In these situations it may be beneficial for employers to encourage employees to spend time, during breaks or after work, exposed to living nature.

Further analysis

In addition to the previously mentioned suggestions, future research could explore whether the effects of nature on mood are dependent on the particular work environment. Larsen et al23 concluded that while plants may have a positive effect in creative environments, they may be detrimental to productivity in workplaces demanding repetitive action. Furthermore, there may be workplaces, such as industrial sites, where some of the psychology effects of living nature could come into conflict with the tasks of the employees. Industries requiring quick reflexes or the operation of heavy machinery, for example, may find a relaxed mood state to be counterproductive to the requirements of the role. In these types of workplace, the introduction of living nature may actually have negative repercussions.

Conclusion

This study examined differences in participants’ moods when their office settings included a live plant, an artificial plant, an aquarium with living fish, a fish screen, or no nature stimuli. A review of the literature suggests that it was one of the first of its kind to investigate whether the living component of nature influences the effect it may have on mood.

The results indicated that living nature is superior to artificial nature in providing restoration and that an aquarium may have a significant impact on improving the mood of employees in their office environment. In essence, the introduction of living nature into the workplace may be a simple and effective way to improve wellbeing for employees. As one passionate advocate of the natural world once said: “Nature can trap us involuntarily, occupy our minds, temporarily remove us from stresses of everyday life, and leave us feeling refreshed and in a better mood.”1

This investigation provides support for the biophilia hypothesis applied to the work environment. As people move into a high-tech world with artificial substitutions for nature,29 designers should consider opportunities to bring real nature inside for the benefit of both workers and – through their enhanced psychological health – the businesses for whom they work. As EO Wilson said: “Life around us exceeds in complexity and beauty anything else humanity is ever likely to encounter.”40

Authors

Chloe Hamman MA Science Hons (BCA) works in organisational development and design. Dr Linda Jones PhD DipTchg MNZPsS MRSNZ is a senior lecturer at Massey University, New Zealand.

References

1. Lewis, CA. Green Nature/Human Nature: The Meaning of Plants in Our Lives. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 1996.

2. Grahn, P, and Stigsdotter, UA. Landscape planning and stress. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening; 2003, 2:1-18.

3. Regan, C L, and Horn, SA. To nature or not to nature: Associations between environmental preferences, mood states and demographic factors. Journal of Environmental Psychology; 2005, 25:57-66.

4. Van der Berg, AE, Koole, SL, and van der Wulp, NY. Environmental preference and restoration: (How) are they related? Journal of Environmental Psychology; 2003, 23:135-146.

5. Kellert, SR, and Wilson, EO. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington DC: Island Press; 1993.

6. Heerwagen, J. Biophilia, Health, and Wellbeing. Restorative Commons: Creating Health and Wellbeing through Urban Landscapes; 2009, 38-57.

7. Grinde, B, and Patil, G. Biophilia: Does visual contact with nature impact on health and wellbeing? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; 2009, 6:2332-2343.

8. O’Haire, M. The benefits of companion animals for mental and physical health. Paper presented at the RSPCA Australia Scientific Seminar, 2009

9. Petty, J. How nature contributes to mental and physical health. Spiritual and Health International; 2004, 5(2).

10. Ulrich, RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science; 1984, 224:420-421.

11. Ulrich, RS. Effects of interior design on wellness: Theory and recent scientific research. Health Care Interior Design; 1991, 3:97-109.

12. de Kort, YA, Meijnders, AL, Sponselee, AA, and IJsselsteijn, WA. What’s wrong with virtual trees? Restoring from stress in a mediated environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology; 2006, 26:309-320.

13. Moore, E. A prison environment’s effect on healthcare-service demands. Journal of Environmental Systems; 1981 11(1):17-33.

14. DeSchriver, M, and Riddick, C. Effects of watching aquariums on elders’ stress. Anthrozoos; 1990, 4(1):44-48.

15. Jones, L. Anxiety in dentists’ waiting rooms: Extracting the facts through complementary quantitative and qualitative methods. Sociologia e ricerea sociale n; 2005, 76-77.

16. Beck, AM, and Meyers, NM. Health enhancement and companion animal ownership. Annual Review of Public Health; 1996, 17:247-257.

17. Edwards, NE, and Beck, AM. Animal-assisted therapy and nutrition in Alzheimer’s disease. Western Journal of Nursing Research; 2002, 24(6):697-712.

18. Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology; 1996, 15:169-182.

19. Ulrich, RS, Simons, RF, Losito, BD, Fiorito, E, Miles, MA, and Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology; 1991, 11:201-230.

20. Asano, F. Healing at a hospital garden: Integration of physical and non-physical aspects. Horticultural Practices and Therapy for Human Wellbeing; 2006, 775:13-22.

21. Shibata, S, and Suzuki, N. Effects of indoor plants on creative task performance and mood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology; 2004, 45:373-381.

22. Kweon, B, Ulrich, R.S, Walker, VD, and Tassinary, LG. Anger and stress: The role of landscape posters in an office setting. Environment and Behavior; 2008, 40(3):355-381.

23. Larsen, L. Adams, J, Deal, B, Kweon, B, and Tyler, E. Plants in the workplace: The effects of density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions. Environment and Behavior; 1998, 30(3):261-281.

24. Lohr, VI, Pearson-Mims, CH, and Goodwin, GK. Interior plants may improve worker productivity and reduce stress in a window-less environment. Journal of Environmental Horticulture; 1996, 14(2): 97-100.

25. Ceylan, C, Dul, J, and Aytac, S. Can the office environment stimulate a manager’s creativity? Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries; 2008, 18(6):589-602.

26. Kaplan, R, and Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

27. Chapman, RJ. Exploiting the human need for nature for successful protected area management. The George Wright FORUM; 2002, 19(3):52-56.

28. Katcher, A, Segal, H, and Beck, A. Comparison of contemplation and hypnosis for the reduction of anxiety and discomfort during dental surgery. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis; 1984, 27(1).

29. Friedman, B, Freier, NG, Kahn, PH, Lin, Jr, and Sodeman, R. Office window of the future? Field-based analyses of a new use of a large display. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies; 2008, 66:452-465.

30. Adachi, M, Takano, Y, and Kendle, A. Psychological ratings of cut flowers, cut greens and artificial plants as table decoration in a university restaurant. JJSPPR; 2001, 1(1):15-20.

31. Shibata, S, and Suzuki, N. Effects of indoor plants on task performance and mood: A comparison between natural and imitated plants. Paper presented at the International Association for People-Environment Studies Conference; 2004.

32. McNair, D, and Lorr, M. Profile of Mood States Bipolar Form (POMS-BI). San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1982.

33. Beck, A. Animal contact and the older person: companionship, health, and the quality of life. Paper presented at the biennial convention of the American Association of Retired Persons, Denver, CO; 1996.

34. Beck, A, and Katcher, A. Future directions in human-animal bond research. American Behavioral Scientist; 2003, 47(1):79-93.

35. Repetti, RL. Short-term effects of occupational stressors on daily mood and health complaints. Health Psychology; 1993, 12(2):125-131.

36. Bringslimark, T, Patil, GG, and Hartig, T. The association between indoor plants, stress, productivity and sick-leave in office workers. Horticultural Practices and Therapy for Human Wellbeing; 2006, 775:117-121.

37. Bringslimark, T, Hartig, T, and Patil, G. Psychological benefits of indoor plants in workplaces: Putting experimental results into context. Horticultural Science; 2007, 42(3):581-597.

38. Kaplan, S, Bradley, J, Luchman, J, and Haynes, D. On the role of positive and negative affectivity in job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology; 2009, 94(1):162-176.

39. Occupational Safety and Health Services. Healthy work: Managing stress in the workplace; 2003. Retrieved from: www.osh.dol.govt.nz/order/catalogue/

stress/managestress.pdf

40. Wilson, EO. Biophilia: The Human Bond with Other Species. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1984.

|

1.1.jpg)

|