Children's Hospitals: The Natural Prescription

Surrounded by nature yet minutes from the city, the new Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne incorporates the latest evidence and research-based design principles to enhance and support healing, reports Helen Wayland.

Reaching seamlessly into its natural setting and bringing the light, textures and forms of the park inside, the concept for the new Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) in Melbourne was inspired by its site. A ‘bushland’ character has been thoughtfully integrated into the delivery of a family-focused healing environment.

The design incorporates extensive positive connection with nature, an imaginative approach to cognitive wayfinding, and a scale that can be easily ‘read’ by people of all ages. Central to the concept is the idea that the children who are the patients, as well as their parents, visitors and staff on site can feel connected to the natural cycle of each day, due to the changing natural light and direct engagement with the parkland setting. A natural palette of textures and colours brings the landscape inside, while the healing potential of a home-like environment, rich with distraction, play and imagination has been explored for every age group.

The new RCH is being delivered as a Public Private Partnership (PPP) under the Victorian Government’s Partnerships Victoria policy, which will see the public sector continue to own and operate the hospital and provide all core clinical services, staffing, teaching, training and research, while the private sector will fi nance, design, construct and maintain the new building.

|

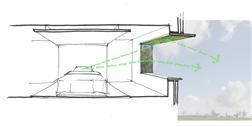

Reflective surface in the windows ensure that even bed bound children can see into the park

|

Easy orientation

The new hospital is located in Royal Park, Melbourne’s largest park, close to Melbourne Zoo and the main roads into the city. “You couldn’t imagine a better site,” says Kristen Whittle, director of Bates Smart, one of a number of collaborators in the Children’s Health Partnership (CHP) consortium, answering the hospital’s ‘world-benchmark’ brief.

“Royal Park is close to the city centre yet feels like you are in the country. It is filled with eucalypt trees, rolling grasslands and big open skies. It has a real feeling of space, openness and air.” Thanks to an allocation of 4.1 hectares, the buildings have been given a low profile, separated into their functional areas in a ‘campus’ arrangement. Threading all together and creating a social heart for the hospital is a central ‘street’.

“In Australia, the amenities in any town are grouped around a key main street,” Whittle explains. “So even if you are a family from a small town, this is a really easy way to orientate yourself.”

As well as a planned shopping precinct, the hospital has a number of other orientation devices linking amenities to the central street. Parts of the Melbourne skyline and the parkland setting will always be in sight along the main street, allowing an instant recognition of the time of day and direction one is facing. There are also several large internal place markers. These include a giant aquarium near the reception desk and room for playful yet massive installations – a timber dinosaur, for example.

The play of light

All sides of the hospital enjoy direct sunlight. To take advantage of all-day natural light, the street was oriented to run north/south, allowing the central street and north-facing garden court at the end of the street to get great midday sun and making the building light, airy and attractive for staff, patients and visitors.

The north-facing wall of the street is glass and opens onto the Great Garden Court, the largest of the gardens surrounding the hospital. With a glazed roof, the central street is naturally lit. Louvres in the roof allow natural ventilation to enter the street and in fi ne weather the doors can be opened to admit natural air currents. Colourful mobiles moving in these air currents create a gentle play of soothing dappled shadows across the space. Walkways and bridges across the higher levels of the street appear much as branches would from a tree.

Externally, a range of innovative sunshades and window treatments merge the buildings into their surroundings. The main west-facing entrance feels like the entry to a treetop canopy due to the curved units of glass that fit like ethereal ‘leaves’ around the facade.

|

The site has a natural fall

|

Fingers into the park

The north building, which houses all the inpatient accommodation, is positioned deepest into the park setting. The accommodation unit is planned as a multi-fi nger-shaped building. Each fi nger is wedge-shaped to allow open social spaces to be centrally located within each section. This also brings views and natural light into the social spaces as well as the bedrooms. “In this way, as the building extends into the park, the park is brought into the building,” notes Ron Billard, principal of Billard Leece Partnership, joint venture architects with Bates Smart.

More than 80% of inpatient rooms have park views, with the rest looking into courtyards. Clever placement of reflective surfaces brings the views inside the bedrooms, so that even children confined to bed can see what’s happening in the garden.

Externally, pre-cast elements fit together almost like a jigsaw, with natural aggregate tones imparting a camouflage

quality to the building. “To enhance this effect we also used some overclad translucent glazed areas, interspersed both to reflect the park inside and to create coloured ‘halos’ around the building in certain areas,” says Whittle. “They almost look like blossom bursting out as you walk around the building. We use the same glass as on the sunshades in the west,

but more intensely saturated with colour.”

The healing power of imagination

Research into the emotional requirements of children of all ages underpins the aesthetic criteria of the project and informs all the design factors and the fi nishes. The intention was not to create a manufactured or cartoonish children’s world but a rich and layered experience, sourced from the natural surroundings, bringing the imagination into play while providing the cosiness and warmth of home.

CHP has developed partnerships with Melbourne Aquarium, Melbourne Zoo and Scienceworks Museum, all of which will provide installations, performance and other content within the hospital to distract and engage imaginations of every age. There are multiple spaces for play, for family contact, and for group activities.

Green in all ways

The building itself is designed to be sustainable, aiming to be Australia’s first 5-Star Green Star Hospital using the Green Building Council of Australia’s healthcare pilot tool. Scheduled to open in 2011, the design is planned to be ‘future proof’, with room to grow as needs arise.

Once the project is completed, including a hotel and refurbishment of older buildings in phase two, much of the old site will be demolished and restored as parkland – with an overall gain in vegetation.

Author: Helen Wayland is a writer and journalist Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne

| Project Facts Box |

|

| Project completion date: |

December 2011 (Stage 1); December 2014 (Stage 2) |

| Contract form |

PPP (Public Private Partnership) |

| Construction Cost |

AUS$960m |

| Project Cost |

AUS$1billion approx |

| Client |

The Department of Human Services |

| Architects |

Billard Leece & Bates Smart with HKS |

| Structural engineer |

Irwin Consult |

| Services and environmental engineer |

Norman Disney & Young |

| Quantity surveyor and planning supervisor |

Bovis Lend Lease |

| Main contractor |

Bovis Lend Lease |

|

1.1.jpg)

|