Sustainability and Evidence: The intersection of evidence-based design and sustainability

The application of sustainable design and evidence-based design strategies often seem to operate in isolation from each other. This study examines where they can, and should, intersect.

Bill Rostenberg FAIA, FACHA, Mara Baum AIA, LEED AP, Dr Mardelle Shepley, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP (principal investigators), with Rachel Ginsberg, MLS.

Sustainable design and evidence-based design are each unique design approaches significantly impacting healthcare architecture today1. Sustainable design promotes buildings that improve ecological health and indoor environmental quality, while evidence-based design advocates healthcare facilities which enable positive health outcomes through the application of best practice strategies informed by research and practical knowledge2.

Although each movement directly impacts current healthcare architecture, each is often implemented in isolation of the other and some even consider these philosophies to be in conflict with one another3,4. For example, how frequently do sustainable goals of reduced water consumption conflict with evidence-based design goals of increasing handwashing compliance? Does the use of HEPA or laminar air flow devices (installed to improve infection control) compromise the energy-consumption efficiency of building-wide air-handling systems?

Are many of the finishes and materials which are well suited to controlling the spread of infection actually hazardous and toxic to the environment? And, perhaps most significantly, does a building footprint that introduces natural daylight into technologically complex healthcare environments (such as surgery, radiology and procedural medicine suites) inherently increase travel distances, compromise desired clinical adjacencies and complicate opportunities for future flexibility and incremental adoption of changes in medical technology and operations

Project overview

The research project, upon which this paper is based, was jointly funded by the Boston Society of Architects, The American Institute of Architects / College of Fellows Upjohn Research Initiative and Anshen + Allen. The purpose of the research was to: identify best practice facility examples reflecting evidence-based design (EBD) and sustainable design (SD) philosophies; determine if evidence-based design and sustainable design approaches are more frequently applied in a mutually supportive and integrated manner, or separately and in isolation of one another; identify the kinds of data being collected by facilities considered to be exemplar, or best practice, representatives of EBD and SD; and solicit opinions regarding the potential for both areas of inquiry to be integrated into a comprehensive and synergistic design process.

Research activities consisted of the following phases:

Phase 1: Advisory groups

Advisory groups were formed to provide direction regarding critical questions about the relationship between evidence-based design and sustainable design that would be addressed in the EBD-SD survey and to identify built healthcare projects which they consider to represent ‘centres of excellence’ in EBD and SD. The principal investigators augmented these facility lists with additional projects identified through a literature review.

Phase 2: Best practice facility survey

Researchers surveyed national experts in evidence-based design and sustainable design to identify notable EBD and SD centres of excellence. Twenty-six experts in each area were emailed a list of projects identified in Phase 1. The national experts were asked to identify the top 10 built healthcare facilities in North America representing best practices in either EBD or SD. Sustainable development experts were only asked to consider sustainable design projects and evidence-based design experts were only asked to consider evidence-based design projects. The results of this survey were used to identify best practice facilities to be surveyed in Phase 3.

Phase 3: SD-EBD survey

Researchers surveyed healthcare administrators at the facilities identifi ed in Phase 2. The administrators had been involved with, or were aware of, the design process for these projects and were involved with the operation of the facilities.

Phase 4: Literature review

For each of the facilities whose administrators responded to the Phase 3 survey, researchers conducted a literature review. This review focused on discussion by the design team and hospital administrators regarding the relationships between issues or strategies associated with both evidence-based design and sustainable design. However, the majority of the articles were not peer-reviewed; as such, they only suggest the quantity and quality of knowledge available to design professionals engaged in healthcare architecture.

Best practice facilities

The evidence-based design and sustainable design experts identifi ed nine EBD and nine SD facilities considered to represent best practices in each subject area. These 18 hospitals are distributed around all regions of the US and represent a range of sizes and programmes. Six of the facilities either have obtained or are pursuing a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for New Construction (LEED NC) rating5; the facilities have collectively acquired all possible levels of LEED certification: Certified, Silver, Gold and Platinum.

Eight administrators from both facility types responded to the surveys. Their responses refl ect an opinion that, overall, EBD and SD are compatible, although some specific implementation strategies may be perceived to be in conflict. These findings are discussed in greater detail in an article currently in review1.

Facility data collection

In general, more of the facilities surveyed are collecting evidence-based design metrics data than sustainable design metrics data. While 88% of EBD and 50% of SD facilities surveyed indicated that they collect data related to EBD topics (such as patient satisfaction and medical errors), only 63% of SD and 12% of EBD administrators reported that their facilities track SD topics, such as energy and water consumption (see Figure 1).

Most of the facilities surveyed (69%) collect only one type of data – evidence-based design or sustainable design. Approximately 12.5% of the facilities collect data on both EBD and SD topics and 18.5% do not collect data related to either EBD or SD. Of the seven facilities that collect EBD data, only one also collects SD data (see Figure 2). This is markedly lower than the total number of facilities (5%) that collect SD data. Of the facilities that collect SD data, half collect EBD data as well. This is markedly lower than the total number of facilities (12) that collect EBD data.

Administrators of the facilities that collected data were asked to identify the type of data they collected. Regarding EBD data, five administrators listed patient satisfaction and two listed staff satisfaction as the data they were most interested in tracking. Patient-related metrics also represented the most frequently cited set of issues among the other EBD metrics identified. Regarding SD data collected, most (60%) were related to energy consumption. Each facility, however, appeared to be measuring it in different ways. Two administrators indicated that they collect data on total energy consumption and recycling.

Other metrics – such as central plant energy use and the use of specific types of energy (steam, electricity, natural gas, etc) – were each identified only once (see Figure 3).

Individuals surveyed were asked two final narrative response questions about the lessons they learned from designing and operating their facilities. For example, administrators were asked what EBD- and SD-related changes they would make if they were to rebuild their facilities. Four EBD and five SD representatives answered this question. Most EBD administrators suggested changing specific design features, such as flooring types or waiting room design. However, only one SD administrator listed proposed changes to specific building elements. Most of the SD administrators’ comments focused on changing the design process (see Figure 4).

In an effort to give the administrators the opportunity to provide additional comments on the larger topics of evidence-based design and sustainable design, the fi nal narrative response question was open-ended. These responses are summarised in Figure 5. Most of the EBD administrators focused their ‘lessons learned’ comments on specific building features, noting that many current models for EBD research place emphasis on discreet physical design features implemented to achieve particular clinical outcomes (such as the installation of patient lifts to reduce patient and staff injuries that may result from lifting patients manually6).

While one surveyed facility is undertaking research that addresses big-picture holistic issues, this appears to be an atypical exception. Most of the EBD and SD strategies proposed are related to well-accepted and acknowledged practices within their respective categories. Only one of the eight evidence-based design building design changes proposed – access to nature – coincides with sustainable design goals, while two of the three sustainable design strategies – linoleum flooring and daylight harvesting – overlap with evidence-based design goals. While one surveyed facility is undertaking research that addresses big-picture holistic issues, this appears to be an atypical exception. Most of the EBD and SD strategies proposed are related to well-accepted and acknowledged practices within their respective categories. Only one of the eight evidence-based design building design changes proposed – access to nature – coincides with sustainable design goals, while two of the three sustainable design strategies – linoleum flooring and daylight harvesting – overlap with evidence-based design goals.

Linoleum is a healthier and more sustainable alternative to vinyl and daylight ‘harvesting’ includes a variety of techniques in which daylight is transmitted internally to otherwise dark deep floor plates. This can be accomplished through daylight fixtures, courtyards, atria or skylights. This concept is important for hospitals, which tend as a building type to use deeper floor plates than do other building types.

A third medical practice are inherent in healthcare facilities, this type of conflict may be more pronounced in healthcare projects that are driven disproportionately by sustainability (versus a more balanced approach that equally considers sustainability and evidence-based design). For example, right-sizing of building systems and equipment is often a sustainable design goal, because running mechanical and other systems at a reduced capacity is typically significantly less energy-efficient than running the same systems at or near capacity – while designing features that provide future flexibility is typically an evidence-based design goal.

If a facility’s systems are right-sized for the immediate demand, there may not be much additional capacity for alternate uses either during initial occupancy or in the future. An optimal solution would be one that efficiently runs systems for initial demands yet also provides for integrated incremental expansion for future demand changes. While such solutions are challenging for any building type, the challenge is more significant for healthcare facilities because utility requirements for equipment are both greater and more likely to change substantially than in conventional facilities. If a facility’s systems are right-sized for the immediate demand, there may not be much additional capacity for alternate uses either during initial occupancy or in the future. An optimal solution would be one that efficiently runs systems for initial demands yet also provides for integrated incremental expansion for future demand changes. While such solutions are challenging for any building type, the challenge is more significant for healthcare facilities because utility requirements for equipment are both greater and more likely to change substantially than in conventional facilities.

Several similar themes emerged from the SD administrators. One theme commonly cited by SD administrators was that opportunities for successful execution of sustainable designs are improved by the ability to address and incorporate sustainability early, frequently and with as many relevant stakeholders as possible. Related to the comments above regarding special equipment, two respondents emphasised the importance of considering the needs of end users or tenants in the design process. This type of comment is frequently cited as being a critical element of the green building process7,8 and also for evidence-based design processes.

Overall, the survey yielded diverse opinions regarding opportunities for compatibility – and the lack thereof – between evidence-based design and sustainable design. One EBD administrator boldly stated: “There is no relationship between evidence-based and sustainable design and they should not be piggybacked,” while two other administrators disputed this notion.

Accordingly, the survey’s premise itself was challenged with comments suggesting that a belief that evidence-based design proposed SD design change – ground source heat pumps – uses the thermal stability of the earth adjacent to a building to improve energy efficiency.

Interpretation of the survey results indicated that SD administrators primarily addressed design process issues while EBD administrators more frequently addressed specific design features themselves. However, only one respondent recommended changing specific building features without also addressing the design process.

Furthermore, one survey highlighted the importance of considering special ‘end-user-requested’ equipment, such as instrument sterilisers, when designing building systems for optimal energy performance. This raises an important issue that such equipment – which is unique to healthcare facilities and thus is not typically factored into building systems designs for other building types – has a significant impact on energy performance. This comment underscores the importance of improving both the design process and the development of specific design details.

Because changes in equipment and and sustainable design are separate and that facilities must “choose one over the other” is faulty. This respondent stressed the importance of finding synergies between strategies that support both goals. Similarly, another administrator commented: “Assuming that an owner is committed to both, one need not be sacrificed for the other.”

Myriad challenges facing those wishing to more fully integrate evidence-based design and sustainable design were underscored throughout the survey. One respondent noted that some standard green building practices conflict with hospital licensure or building code requirements. Healthcare providers and designers who wanted to go green had few resources beyond those developed for generic building types before publications such as the Green Guide for Health Care were developed. Even with the publication of such healthcare-focused sustainability monographs, it remains critical for design teams to enhance their understanding of healthcare-specific building requirements in order to better integrate these with sustainability practices.

Conclusions

Sustainable design projects have a lot to gain from the EBD culture of research and knowledge dissemination, while evidence-based design projects can benefit from the sustainability community’s longevity in quantifying and qualifying performance metrics. Significant research efforts on how to best apply sustainability issues to healthcare architecture are clearly necessary and design teams that are considering collecting data on either sustainable design or evidence-based design issues can look to the Center for Health Design and the US Green Building Council’s National Green Building Research Agenda for help and guidance. While sustainability appears to be better accepted as an integral component of general architectural design today, evidence-based design concepts applied to healthcare architecture have also received much recognition in recent years. There is both the need and opportunity for the two to become better integrated with each other and thus further collaborative growth and development of each is necessary.

Translating knowledge into practice

Research studies such as this one are the first step in cultivating a greater understanding of how the buildings we design affect clinical, environmental, operational and financial outcomes for patients, caregivers and healthcare executives.

Research is but a means to an end – the end being the art and science of designing better buildings which directly contribute to improved outcomes. Each architectural project has its own unique set of opportunities and constraints. Even projects with stated sustainability and evidence-based design goals are often replete with decisions requiring one goal – either sustainability or evidence-based design – to be prioritised over the other. As a follow-up to the formal survey and data collection activities of the research study described herein, we are examining a range of possibilities for how, what appear to be, prioritisation conflicts can be resolved in a more balanced way on projects currently in design.

In response to the question posed in the second paragraph of this paper – “...does a building footprint that introduces natural daylight into technologically complex healthcare environments (such as surgery, radiology and procedural medicine suites) inherently increase travel distances, compromise desired clinical adjacencies and complicate opportunities for future flexibility and incremental adoption of changes in medical technology and operations?” – we have initiated our own inquiry which we refer to as “humanising the deep floor plate”.

As part of this investigation, we are studying a range of design approaches for creating an exemplar surgical and interventional platform that addresses a range of sustainable, or qualitative, criteria – such as natural daylighting, clear wayfinding and creating a humane interior scale – while at the same time meeting evidence-based, or quantitative, criteria – such as providing for future flexibility, maintaining short travel distances between the operating rooms and recovery space, and accommodating complex medical technology that can be shared among various specialists.

In most instances, it is easy to address either the sustainable or the evidence-based design criteria in isolation, but the challenge becomes incrementally more diffi cult when addressing one set of needs without simultaneously compromising the other set.

|

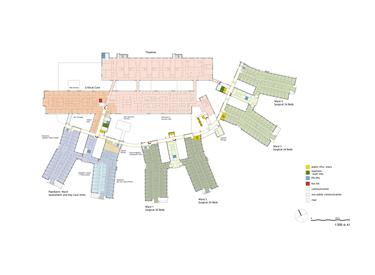

| Figure 6: Surgical platform designed with evidence-based design as a primary driver |

Project priorities

The following paragraphs describe three discrete projects currently in design. Each project has both clearly stated sustainable and evidence-based goals which are successfully addressed by various innovative design concepts. However, the ways in which the surgical/interventional platforms are designed vary significantly from project to project. These variations reflect different site conditions as well as different values and priorities regarding primary versus secondary design drivers.

In other words, while each project satisfies the stated sustainable and evidence-based design goals, one project prioritises the qualitative goals of sustainability, one project prioritises the quantitative goals of evidence based design, and one project prioritises a balanced integration of both sustainability and evidence-based concepts.

Figure 6 illustrates a dense urban hospital where building the maximum allowable site coverage was necessary in order to accommodate the full programme. While there were few opportunities to ‘penetrate’ the deep floor plate with courtyards, skylights or building separations, some opportunities for peripheral corridors to bring ‘borrowed’ natural light into procedural spaces were leveraged. The floor evolved as a deep block of space with indentations minimally carved along a few edges. As a result, critical functional adjacencies remained intact, frequent travel distances for vulnerable patients were kept extremely short and multiple strategies for future flexibility prevailed – but harvesting of natural daylight internally was limited.

|

| Figure 7: Surgical platform designed with sustainable design as a primary driver |

Figure 7 illustrates a similar programme arrayed on a less restrictive site where an abundance of natural daylight triumphed as a driving goal. In contrast to Figure 6, this solution evolved as separate narrow blocks of space connected with bridges or corridors surrounding courtyards and building setbacks to form a composition of sub-components that make up the floor plate. As a result, each room has access to daylight, wayfinding is simplified through one’s ability to see ‘building landmarks’ through exterior windows and the scale of this technologically-complex suite appears humane and intimate. Travel distances, however, are lengthened in some locations and flexibility is somewhat compromised due to the floor’s narrow footprint.

Figure 8 illustrates a hybrid approach where qualitative and quantitative design drivers were balanced to the extent possible. The site is less restrictive than that in Figure 6 but more restrictive than that in Figure 7.

|

| Figure 8: Surgical platform designed with both sustainable design and evidence-based design as a primary driver |

The configuration evolved beginning with a dense deep footprint which was then carefully penetrated by two strategically placed courtyards arrayed in such a way that they separate the procedural zone from the pre-op and recovery zone of the platform, yet retain a relatively deep dimension for each zone. Daylight is harvested both by maximising perimeter and courtyard light and carrying it into procedure rooms with integral windows. The resulting configuration and articulation of the floor minimises critical travel distances, provides multiple opportunities for future flexibility, and yet provides internal spaces that are naturally illuminated and are characterised by clear wayfinding and a humane scale.

Because each project is driven by the unique prioritised values of its respective team, it would be inappropriate to suggest that one project is more successful than another. Similarly, it would be inappropriate to suggest that sustainability is more important than is evidence-based design, or vice versa. Rather, one could deduce that no two projects are identical, especially when designing environments that accommodate extremely complex medical procedures, diverse patient populations and unique caregivers. The success of each project should be determined not by how well it meets any one specifi c design objective, but rather by understanding how each goal has been prioritised for that specific project and by how well each goal has been met relative to the degree that other goals have not been compromised.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the AIA Upjohn Initiative, the Boston Society of Architects and Anshen + Allen Architects for financial support.

Authors

Bill Rostenberg FAIA, FACHA is principal and director of research at Anshen + Allen Architects in San Francisco

Mara Baum AIA, LEED AP is designer and researcher at Anshen + Allen Architects

Dr Mardelle Shepley, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP is director of the Center for Health Systems & Design at Texas A&M University

Rachel Ginsberg, MLS is research coordinator at Anshen + Allen Architects

References

1. Shepley M, Baum M, Ginsberg R, Rostenberg W. Sustainable design and evidence-based design: Perceived synergy and confl ict. Healthcare Environments Research and Design (in review).

2. Hamilton D. The four levels of evidence-based design practice. Healthcare Design 2003; 3:18-26.

3. Harvie J. Redefining healthy food: An ecological health approach to food production, distribution, and procurement. In Designing for the 21st Century Hospital. Papers presented by the Center for Health Design and Health Care Without Harm at a conference sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 2006, Hackensack NJ.

4. Teske K, Mann G. Sustainability and health by design. Medical Construction & Design 2007; 32-47.

5. US Green Building Council. LEED for New Construction and Major Renovations version 2.2. 2005. Downloaded October 2008 from www.usgbc.org/ ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=1095

6. Joseph A, Fritz L. Ceiling lifts reduce patient-handling injuries. Healthcare Design March 2006. Downloaded 17 October 2008 from www.healthcaredesignmagazine.com/ ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&nm=&type=Publishing&mod=Publications%3A%3AArticle&mid=8F3A7027421841978F18BE895F87F791&tier=4&id=36DEC4B1FAE64E77A2CE0 7A13E5270C2

7. Syphers G, Baum M, Bouton D, Sullens W. Managing the cost of green buildings. California State and Consumer Services Agency; October 2003.

8. Mendler SF, Odell W, Lazarus MA. The HOK Guidebook to Sustainable Design, 2nd Edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2005.

Additional sources

1. Baum M. Green building research funding: An assessment of current activity in the United States. US Green Building Council 2007. Downloaded 30 November 2008 from www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=2465

2. Boehland J. Hospital, heal thyself: Greening the design and construction of healthcare facilities. Environmental Building News 2005; 14(6):1-18. Bohn M (Ed). A National Green Building Research Agenda. US Green Building Council Research Committee, November 2007. Downloaded 30 November 2008 from www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=3402

3. Center for Health Design. The Pebble Project Guidebook. Spring 2008. Downloaded 29 November 2008 from www.healthdesign.org/research/pebble/partners/news/documents/PebbleGuidebook_Spring08.pdf

4. Center for Health Design. Pebble Project Research Matrix. Spring 2008. Downloaded 29 November 2008

from www.healthdesign.org/research/pebble/partners/resources/documents/Pebble_Matrix_04.pdf

5. Cohen U, Cohen R. Laguna Honda Replacement Hospital: Topics, research questions, and a research plan. Draft for review by hospital research teams. 2008

6. Green Guide for Health Care. Green Guide for Health Care version 2.2. 2007. Downloaded 1 February 2007 from www.gghc.org

7. Guenther R, Vittori G. Sustainable Healthcare Architecture. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

Guenther, R. Vittori, G. & Atwood, C. (2006). Values-driven design and construction: Enriching community benefits through green hospitals. In Designing for the 21st century hospital. Papers presented by the Center for Health Design and Health Care without Harm at a conference sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 2006.

8. Hackensack, NJ. Mah J, Guenther R, Pierce D. The regenerative hospital: A revolutionary concept. Presented at Greenbuild International Conference and Expo, Boston MA, 20 November 2008.

9. McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry (MBDC). Glossary of key concepts. Downloaded 7 November 2008 from www.mbdc.com/c2c_gkc.htm.

10. Turner C, M. Frankel. Energy Performance of LEED for New Construction Buildings. New Buildings Institute. 2 March

2008. Downloaded 29 November 2008 from www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=3930.

11. United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our common future. 1987. Retrieved 7 November 2008 from www.un-documents. net/wced-ocf.htm.

12. Vittori G. Research agenda for sustainable healthcare: A work in progress. Health Environments Research and Design Journal 2008; 1(2):49-53.

13. Zimmerman G. Healthy and green. Building Operating Management 2007; 54:34.

|

1.1.jpg)

|