Retro-fitting the shopping mall to support healthier communities

How can the US turn car-centric, run-down retail spaces into health-promoting environments? This study proposes turning them into mixed-use ‘villages’ that strengthen communities and are more friendly to walking and public transport

Anthony R. Mawson, MA, DrPH, Jackson State University; Thomas M. Kersen, PhD, Jackson State University; Jassen Callender, MFA, Mississippi State University

During the post-war era of low gasoline prices and prosperity, suburbs and subdivisions have been constructed in formerly rural areas, usually far from workplaces and shopping facilities, accessible only by automobile. Public transportation has usually been insufficient, inefficient or lacking. The need for a personal motor vehicle to drive to work, shop and visit family and friends has been taken for granted. Although the use of automobiles and the larger houses and lots available in the suburbs have provided freedom of movement, they have also led to the loss of forest and farmland, the loss of small-town life and the creation of urban sprawl, lacking defined communities or neighbourhoods, where people increasingly live in comparative social isolation.1 The long-term effects of these changes on human health, wildlife, habitat and other aspects of the environment are not yet fully understood. Living mainly indoors and out of sight of neighbours because of modern appliances such as air conditioners, clothes dryers, televisions and computers, people are connecting more today by text message, email and social media than face-to-face.2

In recent years, political, social and economic trends have combined to challenge the habits of suburbanites and the places they frequent, such as shops and shopping malls, as well as the exclusive use of automobiles for transportation. Foreign wars and financial crises have led to economic decline and trillion-dollar deficits. Gasoline reserves are in question and overall buying power has declined.

There has been much discussion of the isolating nature of urban and suburban life as well as the disruptions in social relationships and their adverse health effects.3-5 At one end of the socio-economic spectrum, the razing of old neighbourhoods for “urban renewal” led to massive social displacement and the loss of supportive social networks.6 Among suburbanites, family connections and friendships are fewer and weaker; families are smaller and both family and friends are increasingly scattered across the country. Membership of civic organisations is also in decline. In his book Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam1 uses the pastime of bowling to exemplify this decline, noting that although the number of people who bowl has increased in recent years, the number of people bowling in leagues has decreased. He suggests that declining membership of such social organisations threatens democracy because, by “bowling alone”, people do not participate in the civic discussions that tend to occur in a league environment. The overall decline in personal interaction – the traditional basis of social life, enrichment and education – has reduced the active civil engagement required for a strong democracy. Disengagement from political involvement is seen in declining voter turnout, attendance at public meetings, serving on committees, and working with political parties.

Americans are said to be increasingly distrustful, not just of government7 but of one another, witnessed by the many walled and gated communities that have arisen to meet a rising tide of paranoia and fear of crime. Tenuous contacts with one’s neighbours not only contribute to distrust but mean that such people cannot be relied upon for assistance in times of crisis. According to Putnam,1 the social capital (ie, goodwill and tangible help from the community) that was once available has declined in the US since the early 1960s. Participation in national organisations and in social activities such as picnics, dinner parties and card games has also declined.

Social bonds and connections in America have weakened over the past half century and social networks have become smaller due to reduced social interaction.8 Support for this observation comes from the General Social Survey (GSS) on changes in social networks between 1985 and 2004.9 In 1985 the GSS collected the first nationally representative data on “confidants with whom Americans discuss important matters”. In the 2004 GSS, changes in core social networks were reassessed. The major findings were as follows:

• Discussion networks were smaller in 2004 than in 1985

• The number of people saying they had “no one to discuss important matters with” nearly tripled

• Average network size decreased by about a third, from 2.94 in 1985 to 2.08 in 2004 (a loss of one confidant in three)

• The typical respondent reported having no confidant, whereas in 1985 the typical respondent had three confidants

• Both kin and non-kin confidants were lost in the past two decades, with a greater loss of non-kin ties. This has led to networks centred on spouses and parents, with fewer social contacts through voluntary associations and neighbourhoods.

The shrinkage of social networks reflects an important social change in the US, where the greatest decrease in close bonds occurred between neighbours and voluntary group members. McPherson et al9 conclude that community and neighbourhood ties have weakened dramatically. Virtual social media’s impact has been to create a larger network of weak social relationships rather than to strengthen bonds between close friends and family. Spending time on the internet has moreover been found to reduce interactions with family members; for every minute spent using the internet, a third of a minute less was spent with family.10 In a study of internet users over a one- to two-year period, time spent using the internet was inversely related to family communication and to the size of participants’ local and distant social networks.11 The shrinkage of social networks reflects an important social change in the US, where the greatest decrease in close bonds occurred between neighbours and voluntary group members. McPherson et al9 conclude that community and neighbourhood ties have weakened dramatically. Virtual social media’s impact has been to create a larger network of weak social relationships rather than to strengthen bonds between close friends and family. Spending time on the internet has moreover been found to reduce interactions with family members; for every minute spent using the internet, a third of a minute less was spent with family.10 In a study of internet users over a one- to two-year period, time spent using the internet was inversely related to family communication and to the size of participants’ local and distant social networks.11

Declining social networks and personal interaction are not only a threat to democracy, according to Putnam,1 but a threat to health and social wellbeing. Man is a social animal with needs for physical contact and nurturance that have profound implications for health and disease. Multiple studies have shown that the existence of close personal relationships and frequent social interaction are essential to good health, and those lacking strong social ties are at increased risks of illness and death from all causes.12-15

The positive effects of close community ties on health and longevity were revealed in a now-classic 30-year study of members of the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania, made up largely of Italian immigrants.16 In the early 1960s, the town was noted for having an exceptionally low death rate from ischemic heart disease (myocardial infarction), less than half that in an adjacent town, Bangor, which lacked strong community ties. Yet smoking and unhealthy dietary habits were as common in Roseto as in neighbouring communities. In the early 1960s, Roseto was a close-knit community where families often ate together, enjoyed frequent social gatherings and entertaining, and had many strong civic organisations. In later years, as Rosetans adapted to the American way of life and began to seek better paying jobs and moved to the suburbs, their death rate from MI rose to equal that of Bangor.

Rosetans who had been tested in 1962-63 and experienced a fatal MI by the year 1990, or had a well-documented heart attack and survived, were compared to unaffected controls. As expected, high cholesterol levels were associated with a two-fold increased risk of MI. Yet fewer than 20% of those with high cholesterol levels experienced an MI over the 30-year period. There were also no significant differences between the coronary patients (survivors or otherwise) and matched controls in terms of the standard risk factors of smoking, hypertension, diabetes or obesity. These findings were interpreted as suggesting that, despite having these risk factors, Rosetans tended not to succumb to MI because of the protective effect of strong social bonds and networks against heart disease.17

Even more impressive are studies indicating that coronary heart disease can be reversed by participation in programmes that include frequent and intense social interaction. In his interventional studies of high-risk patients with heart disease, Dean Ornish included dietary restriction, smoking cessation and meditation as well as frequent group meetings in which participants were encouraged to interact openly and warmly with one other. Ornish et al18, 19 reported that the extent to which participants “opened up their hearts” to other people in these groups over the one- to two-year programme was paralleled by the increase in the patency of their coronary blood vessels, as shown by percutaneous coronary angiography.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the suburban way of life and associated decline in social relations have adverse effects on health and longevity. At the same time, there has been a drastic change in the general economy: consumer spending is expected to decline to what it was about 10 years ago, and a new pattern of frugality will remain.20, 21 Retail material goods sales will likely suffer most and not rebound from recessionary spending levels. Consumers are also less oriented towards spending and more inclined towards family, community and the support of local businesses.22

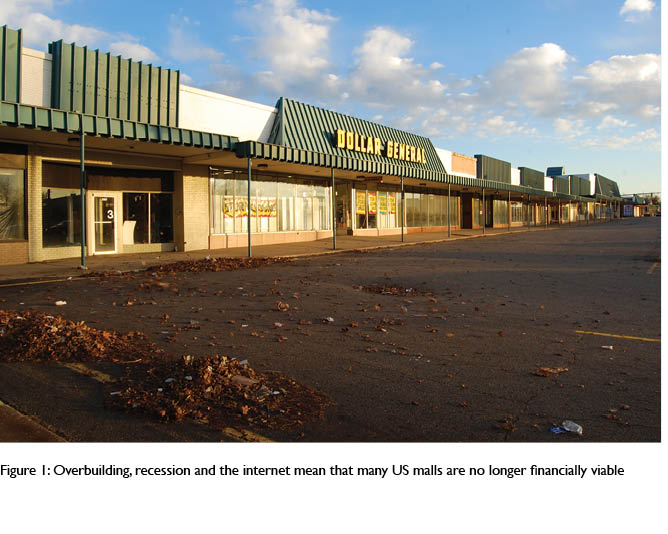

Overbuilding, global recession, increasing internet sales, the decline of department stores and changing consumer values have combined to create what has been described as the “perfect storm” for shopping centres and malls. Retail and restaurant sales have declined and store vacancies are accelerating. Many shopping centres and malls are in serious financial trouble and are searching for strategies to become viable again. According to White Hutchinson, “root causes rather than just symptoms need to be determined and then addressed in order to cure the ills. Fixes are never simple or easy. An overall strategy, often requiring repositioning and some redevelopment of the shopping centre, must be formulated. Such an analysis and strategy is often best accomplished by an outsider, lacking pre-existing biases.”23

From shopping centre to village

We co-authors – an epidemiologist, a social scientist and a professor of architecture affiliated with a Community Design Center – propose herein a practical solution that could be applied to any ailing shopping mall and could lead to increased consumer activity, profitability and sustainability. Our central idea is that malls can be kept vital by retrofitting them to serve additional essential purposes; that is, by transforming them into village-like communities. This could entail building several levels of apartments and offices above the shops below (if structurally feasible) or designing adjacent new residential structures.

To create a village it will be necessary to provide all of the amenities of a village or small town, ie, a butcher, baker, grocer, post office, auto repair shop, hair salons, cafes, restaurants, newsagents, etc, as well as an administrative structure, community centre and meeting room. The size of major stores that depended on a high volume of traffic may have to be reduced, but smaller shops could be added, allowing “mom and pop” stores to reappear. It may also mean more business for stores that have not done well commercially in traditional shopping malls, such as custom framing and art shops.

While the custom of “going out to the mall” may be declining in the US for the many reasons described above, people may be more likely to take advantage of the facilities offered by shopping malls if they lived there, as part of a village-like community where they would meet and interact regularly with others and where store owners would become neighbours. This concept could resolve the simultaneous problems that beset the current suburban lifestyle: firstly, having to drive great distances in some cases, often in different directions, to access workplaces, schools, shops, churches and friends; and secondly, the lack of availability of close friends and family and of face-to-face interaction. Retrofitting and transforming ailing shopping malls into villages would at once bring new life and business to these facilities as well as bring people into closer proximity to their everyday needs; it would create opportunities for employment, enhance social networks and relationships, and at the same time reduce the need for and use of motor vehicles. The proposed retrofitting utilises existing infrastructure, entails less need for vehicular use, and would serve to increase social interaction and the quality of social relationships.

The vision is to transform ailing shopping malls into self-sustaining residential, shopping and office spaces that would be identified as villages, where people of all types and ages can live comfortably and access all essential and desired amenities on foot or bicycle. In addition to physical retrofitting, support and guidance would also be provided to the new residents and tenants to establish a village social administrative structure.

Implementing the proposed retrofitting programme would comprise the following:

• Building two to three storeys above shopping malls or designing new structures in adjacent former parking lots to provide mixed-use residential/office space

• Arranging for parking close to residences and offices

• Organising a village administrative structure, driven by community members

• Organising weekly markets inside or adjacent to malls, eg farmers’ markets and/or flea markets and activities such as fairs, exhibitions, musical or other events

• Creating (or modifying) essential facilities and shops in addition to those already provided in the shopping mall, including but not limited to a post office, butcher/fishmonger, bakery, hair salon, fitness facilities, medical/dental clinics, a community centre, cinema and tavern.

Retrofitting shopping malls into village-like places would be expected to ensure a high level of social interaction and contentment as well as commerce. Visitors would be attracted by the excitement and intimacy of the new “villages”, with all their added advantages and amenities. Many readers will recall the American TV programme Cheers, and its portrayal of a tavern with a close-knit clientele where “everybody knows your name”. Shopping malls could similarly be altered to become villages where people would quickly grow acquainted with one another; where shopping can be done on foot; where people can also be employed in many cases; and where all of the amenities of a “true” village are provided, including a village administrative structure.

Determining feasibility

What would be needed to determine the feasibility of such a venture at a given site? We envision a two-phase process: 1) background research, and 2) specific applications.

Phase I: Background research

• Case Studies: To prepare for work of this complexity and to ground it in terms of financial viability, up to five successful “live and work” revitalisations of existing shopping centres in mid-size American cities would be sought and described, comparable to that of the mall in question (the “target mall”).

• Sociological Analysis: To determine the social-psychological impact of the proposed architectural and social transformation at each site, and historical survey and socio-cultural analysis would be carried out as well as an opinion survey of shoppers at the site, to assess the level of community readiness and interest in participating as potential residents or tenants.

• Materials and Structural Research: Construction materials and methods utilised in many American shopping centres are structurally insufficient to support vertical expansion. Traditional methods for adding structural capacity are also costly and commercially invasive in terms of downtime to existing occupants. To overcome this, existing methods and models would be analysed and alternative solutions proposed. This research would allow for rapid structural feasibility assessment of selected existing structures.

• Code/Zoning Analysis: Existing codes and zoning regulations enforced in many municipalities limit building density and foster segregation of activities. Zoning ordinances and building codes at each site would be reviewed and compared with best practices being enacted in communities around the country.

Phase II: Specific applications

• Case Studies/Demographic Comparisons: Results of the Phase 1 review would be compared to the specific demographic and other features of the target mall and to the immediate context and surrounding neighbourhoods. This information would help determine the economic viability and percentage of space to be allocated to various uses at each site.

• Materials/Structural Research: Existing structural conditions would be reviewed in relation to the results of research from the Phase 1 materials/structural analysis, to provide a guide for proposals relating to the targeted mall. This would provide an estimate of the maximum extent of vertical expansion. These research findings would be turned over to the selected licensed design professionals for the implementation phase.

• Code/Zoning Analysis: Local demographics and proposed building usage would be compared to existing codes and ordinances enforced at the site of the target mall. Drawing on best practices revealed in the Phase 1 analysis, recommendations would be offered and assistance provided to the owner/manager in preparing documents needed to apply for zoning modifications.

• Architectural Programming: Information gleaned from the three immediately preceding steps would be combined with a survey of existing conditions (parking, total footprint, net-to-gross ratio, size and location of existing mechanical infrastructure). An overall report on proposed uses, square footages, key proximities and other relevant issues then would be prepared for implementation by licensed design professionals.

• Concept Design: Although the final design would be the responsibility of the sponsor’s architect, conceptual sketches and renderings would be developed to establish the project’s image and to assist in marketing efforts.

• Preliminary Cost Estimate: Based on the programme and conceptual design, a preliminary cost estimate would be prepared to facilitate initial discussions with the sponsor and/or investors and to establish phasing priorities should the total scope of work prove too large for implementation in a single phase.

• Report Preparation: These activities would include discussing and synthesising the data, creating appropriate graphics and tables, and offering evidence-based recommendations.

Discussion

An entire way of life is changing in America, and with it, traditional concepts and methods of shopping and the use of certain shopping facilities. Shopping for necessities will continue, of course, but the habit of driving to malls to shop is increasingly under pressure to change. With ready access to multiple suppliers and catalogues and instant access to prices, discounts and easy methods of payment, shopping is increasingly done online for more expensive items, saving petrol and saving time. As noted, several emerging trends now challenge the continued viability of shopping centres and malls. At the same time, there is increasing awareness of attenuated connections to family, friends and community, and many feel the need for a more permanent “home”.24 With the seemingly endless recession, rising fuel prices and declining buying power, excitement at the prospect of shopping at the mall has dimmed. A new perspective on life is emerging: people are “making do” and focusing more on others for activities and entertainment, while confronting the reality of having fewer close friends and family to visit than they would wish. This may act as a stimulus for seeking a small town or village way of life, possibly one that, for older people, was experienced in childhood.

The strategy proposed here for addressing these diverse trends, while salvaging the existing infrastructure, is to retrofit ailing and abandoned malls into village-like places such as Roseto, Pennsylvania, where, a generation ago, a thriving community, with strong social networks and low cardiovascular disease mortality rates, was lost. This occurred when the residents, mainly Italian immigrants, followed the American dream of suburban living, prosperity and self-determination that led to their gradual dispersal and resultant social isolation.

The conversion of shopping malls into villages would combine residential living with business and shopping facilities and provide all of the amenities and services that are typically available in a village; it would also offer residents multiple opportunities to establish social networks and to recreate a more communal lifestyle. Communities would develop in which people comfortably live, shop for basic necessities, enjoy other amenities and, in many cases, work on site, while continuing to enjoy the mall’s features.

The growth of shopping malls paralleled the rise of suburbia in the 1950s through to the 1970s. Planners then had little regard for fuel economy, the environment or for fostering walkable spaces. This exuberant period of growth in America did not last, however, and many shopping malls around the country are failing or abandoned.3 Of the 2,000 regional shopping malls nationwide in 2001, 19% were considered in danger by the Congress for the New Urbanism and PricewaterhouseCoopers. In many cases, poor economic performance was compounded by site or location characteristics that made a turnaround unlikely as long as a conventional retail mall format was retained. This has created areas known as “greyfields”, largely abandoned or underused spaces that nevertheless offer opportunities for mixed-use areas that combine work, home and other facets.

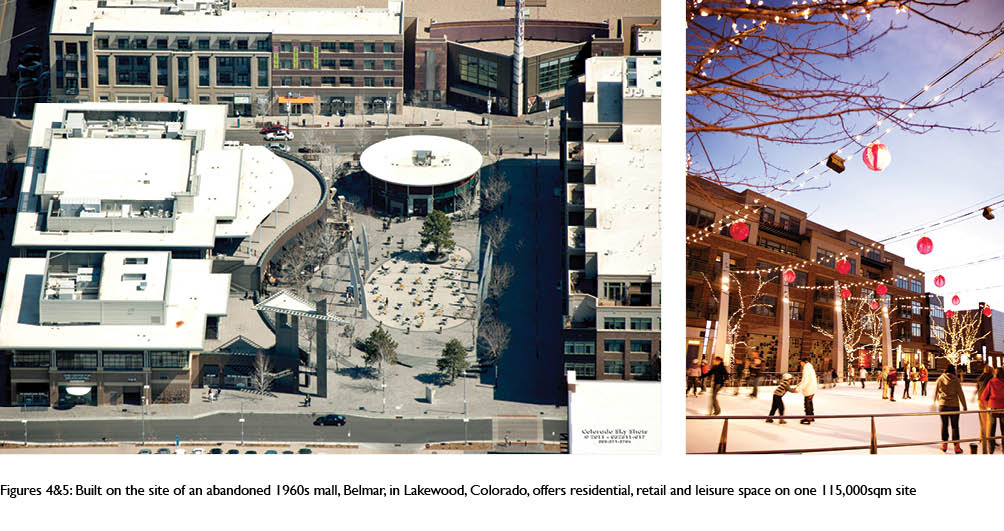

Such models clearly require major changes in thought and practice with regard to zoning, developer/community leader commitment, and other factors. The vision and support of lenders, developers, and community leaders will be critical in facilitating the conversion of ailing or abandoned shopping malls into mixed-use locales. However, when all of the necessary elements come together, the vision can be realised. For instance, Belmar community in Lakewood, Colorado, on the site of a 115,000sqm (1.4m sq ft) abandoned shopping mall built in the 1960s, has become a mixed-use development with shops, homes, and offices in close proximity to one another.25

In her book Retrofitting Suburbia, Ellen Dunham-Jones26 discusses the retrofitting of ailing shopping malls as part of a broader agenda to retrofit suburban areas as a whole (see also Dennis-Jacob27), making them more desirable places in terms of aesthetics and convenience but also in terms of the overall health of the population. She addresses shopping malls as a modern, indoor version of the traditional marketplace and notes their growing struggle to survive in an increasingly competitive retail environment. She suggests that shopping malls, as “core” areas of many suburbs, present opportunities for retrofitting as mixed-use environments that can also contribute to making suburbs more sustainable while maintaining the malls’ commercial functions. Noting that the retrofitting of malls is an increasing practice in North America, Dunham-Jones proposes that parking areas surrounding malls could be converted into high-density buildings, including residential units, and that improved conditions for walking and biking should be provided as well as increased public transportation, thereby creating a livable and sustainable part of the suburban environment.

Here we have sought to contribute to this perspective by suggesting that ailing shopping malls could be usefully retrofitted not just as mixed-use places but specifically as “villages” within the larger suburban environment, acquiring their own identity in relation to surrounding areas. We have also outlined a method for assessing the architectural, regulatory, economic and social feasibility of implementing such plans. Subject to establishing the feasibility and acceptability of such concepts at a given site, a masterplan would be developed for implementation and evaluation. Retrofitting shopping malls into villages could save these commercial structures and in some cases the retail facilities themselves, as well as reduce encroachment on greenfield areas, and help to strengthen the community and spiritual life of the country.

Authors

Anthony Mawson is an epidemiologist and social scientist and a visiting professor in the School of Health Sciences, College of Public Service, Jackson State University, Jackson, Mississippi. The inspiration for this paper was his early life in the English village of Kings Langley, Hertfordshire. Thomas M. Kersen, PhD is assistant professor, Department of Criminal Justice and Sociology at Jackson State University. Jassen Callender is associate professor at Mississippi State University and director of the School of Architecture’s Jackson Center; his areas of research include the analysis of urban systems, visual perception, and philosophical constructions of desire. He has presented internationally on issues of sustainable urbanism.

References

1. Putnam, RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000.

2. Zhao, S. Do Internet users have more social ties? A call for differentiated analyses of Internet use. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2006. 11(3), article 8. Accessed at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue3/zhao.html

3. Baumgartner, MP. The Moral Order of a Suburb. Oxford University Press: New York; 1998.

4. Greer, S. Urban Renewal and American Cities. Bobbs-Merrill: Indianapolis; 1965.

5. Stein, M. The Eclipse of Community: An Interpretation of American Studies. Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey; 1960.

6. Fullilove, MT. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. Random House, New York; 2005

7. www.nytimes.com/2011/10/26/us/politics/how-the-poll-was-conducted.html?_r=1

8. Myers, DG. Close relationships and quality of life. In Kahneman, D, Diener, E. and Schwarz, N. (eds.). Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Russell Sage Foundation: New York; 1999.

9. McPherson, M, Smith-Lovin, L, Brashears, ME. SociaIsolationAmerica: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review 2006, 71:353-375.

10. Nie, NH, and Hillygus, S. The impact of internet use on sociability: Time-diary findings. IT and Society 2002, 1(1):1-20. www.ITandSociety.org

11. Kraut, R, Patterson M, Lundmark, V, Kiesler, S, Mukopadhyay, T, and Scherlis, W. Social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist 1993, 53(9):1017-1031.

12. Montagu, A. Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin. Columbia University Press: New York; 1971.

13. Ornish, D. Love & Survival: 8 Pathways to Intimacy and Health. Harper Collins: New York; 1998

14. Thoits, PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health & Social Behavior 2011, 52(2):145-61.

15. House, JS. Social isolation kills, but how and why? Psychosomatic Medicine 2001, 63(2): 273–274.

16. Bruhn JG, Wolf, S. The Roseto Story: An Anatomy of Health. University of Oklahoma Press: Oklahoma City; 1979.

17. Wolf, S. and Bruhn, JG, with Egolf, BP, Lasker, J and Philips, BU. The Power of Clan: The Effect of Human Relationship on Coronary Heart Disease. Transaction Publishers, Rutgers University: New Brunswick, New Jersey; 1992.

18. Ornish, DM, Brown, SE, Scherwitz, LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary atherosclerosis? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet 1983, 336(8708):129-33.

19. Ornish, D. Dr. Dean Ornish’s Program for Reversing Heart Disease. Random House: New York; 1990/Ballantine Books; 1992.

20. Standard & Poor’s Equity Research,

www.standardandpoors.com

21. Moodys Analytics, www.economy.com

22. Demise of the stuffed; birth of the grounded consumer. www.whitehutchinson.com/leisure/articles/demise-of-the-stuffed.shtml

23. The Grounded Consumer: Changing the Paradigm of Shopping Center Entertainment. www.whitehutchinson.com/leisure/articles/Grounded_Consumer. shtml

24. Smith, K, and Zepp, I. Search for the Beloved Community. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press; 1974.

25. Congress for the New Urbanism; 2005. Malls into Mainstreets. An In-Depth Guide to Transforming Dead Malls into Communities. Accessed at www.mrsc.org/artdocmisc/cnumallsmainstreets.pdf

26. Dunham-Jones, E, and Williamson, J. Retrofitting Suburbia, Updated Edition: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

27. Denis-Jacob, J. Retrofitting Suburban Shopping Malls: A Step Towards Metropolitan Sustainability. N.p., 6 May 2011. Web. 20 Jan. 2013.

www.geographyjobs.com/article_view.php?article_id=243.

|

1.1.jpg)

|