Project Report - Arts and Health

Emerging artistry

Close collaboration between architects and artists is paying dividends in intensifying connections between place and people. Veronica Simpson explores the latest international innovations

This is an exciting time for art in healthcare environments. Judging by recent high-profile examples, it is now becoming standard practice to bring artists on board at an early stage in a building’s development, often leading to inspirational collaborations between artists and architects. Increasingly, art consultants or strategists are being given overarching roles in placing diverse works throughout a building to create a far more compelling, unified scheme with a coherent, patient-focused sensibility.

Joanna Espiner, senior project manager at Willis Newson, one of the UK’s leading art consultants, agrees that recent years have seen rapid evolution in this field, particularly in the UK – driven partly, she says, by the fact that any scheme aiming for BREEAM excellence needs to have an art consultant on board, working closely with artists, architects and stakeholders to ensure a better fit, both with the building and the community.

So what does this growing partnership between artists and architects throw into the healthcare design equation?

|

| UCLH atrium |

Unrestricted exuberance

Jane Willis, director of Willis Newson, says: “Because an artist is coming in to work as part of a huge building but not working on the building – they are not responsible for it – they can bring a really intense focus and playfulness. They can really think about how to solve things and challenge and push the boundaries. The other thing I see coming through is a real poetic sensibility.”

This is true not just of artists but also clients. Ten years ago, for example, some of the creations that Studio Weave – artists, architects and designers – have recently come up with for healthcare settings would have been inconceivable. And this can only be because clients have become more aware of the value of a skilled, well executed and high-quality intervention (or, perhaps, because art consultancies have honed their ability to convince them of the benefits).

Studio Weave and Willis worked together at Bristol Royal Infirmary’s patient ward to try to solve an acoustic problem with the new building. Making reference to the city’s naval and shipping past, Studio Weave conceived of a giant sculpture made of rope, now weaving through the atrium, which provides both a welcoming contrast to the clinical spaces around it and a valuable acoustic baffle. Likewise, in Great Ormond Street, an uninspiring interim space between a new building and an old one (scheduled for demolition but not for a few years), has now been transformed into the ‘Lullaby Factory’ – a collection of gramophone trumpets and copper pipes that play lullabies to listening children, courtesy of Studio Weave’s high-spirited approach to problem-solving.

What art, when delivered at its best, can bring to a building is to render humane, magical and uplifting that which might otherwise be clinical, practical or banal.

But it’s not just art’s ability to delight and surprise that is being harnessed in a good scheme. Working together with enlightened clients and architects, artists are being given the opportunity to develop far more sophisticated responses specific to the environment, the client and the patient group. This can take the form of turning dead space into something delightful (as with the Lullaby Factory); or diminishing the boredom of waiting during a day’s consultations at a busy ambulatory day centre; or, perhaps, creating a quirky and personal narrative around a small speciality healthcare building. It can also play a major part in generating a connection with community and local history within a big, impersonal new hospital facility; and it can even turn a healthcare building into a tool for assessment.

University of Kentucky Chandler Medical Center, USA

AECOM’s new 1.2m sq ft replacement hospital, University of Kentucky’s Chandler Medical Center, integrates architecture with art thanks to a formal Arts in Healthcare programme. The Arts Committee worked closely with architects, interior designers, IT and landscape architects to plan for art locations from the earliest stages, while raising around $3m through private donations.

Large-scale commissioned artworks are placed at strategic wayfinding points; the local tradition of folk art is supported with a special collection, exhibited in the Patient Education Center, directly off the main entrance; an ongoing live arts programme is staged in a 305-seater auditorium. A huge interactive media wall stretches along the back of the main lobby area, with a changing montage of film footage and stills photography displayed across multiple screens to reflect the state’s diverse culture and traditions.

Elsewhere, a 6,000 sq ft patient waiting area offers a lounge/gallery atmosphere, animated by paintings, sculptures and tapestries from Kentucky artists. In patient rooms, inspiring regional landscape photography is showcased, with pieces selected by hospital staff.

It was the winning project in this year’s IADH Academy Awards International Use of Art in the Patient Environment category.

Client: University of Kentucky HealthCare

Architecture, interiors and art co-ordination: AECOM

Budget: Construction $231m core/shell; $112m fit-up; art budget $3m

Completed: May 2011

Where others fear to tread

In planning the University College London Hospital (UCH) Macmillan Cancer Centre – the UK’s first ambulatory cancer facility – Hopkins Architects worked with strategist Morag Myerscough to create a series of pieces that would function, according to Myerscough, as “things to make you think about other things”.

During an Architects for Health seminar in London this June, Guy Noble, arts coordinator for UCH, and Hopkins partner Sophy Twohig described the main challenge for the building as “the management of waiting”, adding: “There is a main waiting space for 150 people and then sub-waits on every floor. We realised that what this does is create opportunities to enjoy art.” The resulting artworks – including a print from iconic pop artist Peter Blake and a tapestry from Turner Prize winner Grayson Perry – are a far cry from the tame posters of flowers or pastoral landscapes that would, if you were lucky, typify most hospital waiting areas once upon a time. Not for nothing did the building (and its art) win the Royal Institute of British Architect’s National Award in 2012, while it also won UCLH a RIBA award for client of the year. Says Noble: “There’s a tendency to water down art in healthcare settings. We really didn’t want to do that.”

Many of the works are provocative and problematic, in ways that would cause many a conservative healthcare client to run a mile. For example, artist Stuart Haygarth, after consulting with a panel of patient representatives, created a striking atrium sculpture/mobile made from pieces of colour-themed, mostly plastic flotsam collected along the south coast of England, along with some of the patients’ own contributions. Noble says: “Putting a lot of rubbish in an NHS hospital is not without its challenges.” The items were given an ultraviolet sterilising treatment, washed and then hung. Elsewhere, Grayson Perry has placed a tapestry exploring themes of life and death, titled ‘What will survive us is love’ “We do have a tendency to patronise patients and think they won’t want to talk about death,” says Noble. “But actually they do. And Grayson isn’t afraid to go into that territory.”

|

|

| Sunshine House, kids play with enamel tile |

Sunshine House voids |

Some would regard even that as tame compared with audio-visual piece ‘Anarchy in the Organism’, by Simeon Nelson: an animation and soundscape of a normal living cell passing through different states of cancer. Says Noble: “I know the patients found this a tremendously challenging but rewarding experience, and they particularly enjoyed being able to discuss their cancer with an artist.”

Many of the pieces were donated by the artists, which meant that the budget for this impressive building went a lot further.

A rather different, quirky and personal narrative was required by the Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospital (RB&H) for its new Centre for Sleep, based in a refurbished Victorian fire station. The RB&H Arts team took the unusual step of commissioning a single cartoonist and illustrator, Steven Appleby, to come up with all the diverse art interventions, from signage, in his characteristic scrawling handwriting, to murals depicting a humorous mind map of how sleep occurs, as well as illustrations on glass in the foyer. With his perceptive and light-hearted take on human frailty, Appleby’s designs combine to create a strong and appealing narrative to patients’ experience of the building, as well as a unified character (it was awarded Highly Commended in the IADH Academy Awards Use of Art in the Patient Environment category this year).

Marily Cintra, director of the Health and Arts Research Centre in Australia, and lead judge of the Art in Healthcare Environments category at the 2013 IADH Academy Awards, was particularly struck this year by the role that art is playing to intensify engagement with patient – and local – communities. She says: “Where art’s purpose used to be seen as purely decorative, now I feel that it is widely recognised that art has a real function as part of the environment, not just in enhancing health outcomes but in connecting people.”

This year’s category winner, the University of Kentucky’s Chandler Medical Center, is a case in point: an extensive and diverse arts programme has been put in place to reinforce local and regional identity (see case study, p47).

Global Fund MDF TB Hospital, Limpopo Province, South Africa Global Fund MDF TB Hospital, Limpopo Province, South Africa

One of the world’s most afflicted regions for TB as well as HIV/Aids, South Africa’s health officials have been trying to address the need for humane and efficient treatment facilities that reduce cross-infection. In collaboration with CSIR research facility, Hospital Design Group (HDG) Architects devised a new approach to long-term accommodation of patients with drug-resistant TB, in which art plays a pivotal role. The single-storey buildings are grouped around a series of courtyards where formal sculptures by local artists create focal points, in the hope of encouraging patient, staff and visitor engagement. Colour used around the building has been chosen to highlight certain seasons and indigenous vegetation, to maintain a sense of connection with the outside world.

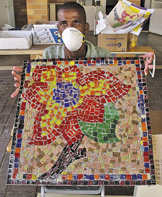

Last but not least, local mosaic artists have been brought in to mastermind elaborate mosaic workshops for the patient groups, which have proved so popular that they have been taken on as an enduring part of patient therapy, resulting in vibrant patient artworks that are displayed on easily mountable and replacable 60cm x 60cm panels attached to the ward wall. Landscaping of the courtyard gardens has also been carefully considered, with a rich variety of plants, colours and forms offering vistas and shading. Patients are also encouraged to get involved in gardening and garden maintenance, providing a useful and positive role within the patient community, as well as skills they can take with them when they leave. Last but not least, local mosaic artists have been brought in to mastermind elaborate mosaic workshops for the patient groups, which have proved so popular that they have been taken on as an enduring part of patient therapy, resulting in vibrant patient artworks that are displayed on easily mountable and replacable 60cm x 60cm panels attached to the ward wall. Landscaping of the courtyard gardens has also been carefully considered, with a rich variety of plants, colours and forms offering vistas and shading. Patients are also encouraged to get involved in gardening and garden maintenance, providing a useful and positive role within the patient community, as well as skills they can take with them when they leave.

It was Highly Commended in the IADH Academy Awards, International Art in the Patient Environment category, 2013.

Client: Limpopo Department of Health, South Africa and Global Fund, Pretoria

Architects: Hospital Design Group with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)

Cost of construction: R44m

Consultants: Sakhino Health Solutions

Give me sunshine

When it comes to art being used as a strategic tool in patient treatment and engagement, there can be few more convincing examples than Sunshine House children’s development centre in south London.

Five years after it opened, there’s no doubt in the minds of staff that the combined art and architecture programme has made a difference not just to the quality of the environment but in their ability to assess and entertain patients. Sunshine House is a multiple award-winning £7.7m project, undertaken by AHMM in 2007 on behalf of Building Better Health, combining a variety of services for children with complex needs. Client Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, through its charity, has a commitment to spend 1% of capital costs on art in all its sites. Modus Operandi art consultants worked with the architects from early on in the design process to identify two principal artists – Dutch artist Milou van Ham and London-based artist Jacqueline Poncelet – who could generate layers of interest, colour and movement into the building.

The artworks are concentrated on the ground floor and basement, where the reception area, breakout areas, consultation rooms and gym/physio rooms are located. Three voids have been punched into the elongated rectangle of the building to bring light into the basement and help it penetrate deep into corridors on every level. Milou has animated each void with a large, hanging geometric sculpture, which plays on specific words she developed in workshop consultations with local children. The same words appear reversed, upended, inverted and scrambled on glass panels around the voids and are raised to encourage touch and exploration by the many visually impaired visitors.

Southmead Learning & Research and Pathology Buildings, Bristol, UK Southmead Learning & Research and Pathology Buildings, Bristol, UK

In partnership with North Bristol NHS Trust, Willis Newson art consultancy delivered a public art strategy from very early on in the design and construction of new learning and research facilities, and pathology buildings on the Southmead Hospital site in Bristol. The project was part of the ‘enabling’ phase of the PFI redevelopment of the hospital, due for completion in 2014. Artists worked alongside architects Avanti and building contractors Laing O’Rourke to weave bold, enriching materials and colours into the fabric of the two buildings.

Lead artist Kate Blee designed the colour and composition of the exterior glazing, which clads both buildings. A rich pattern of greens, greys, blues and russets alternate with clear glazing, and this same palette is deployed inside the building. In addition, Blee designed two large ceramic wall pieces for each building’s atrium entrance. They reflect light and incorporate tactile, dynamic surfaces to animate and arouse curiosity in the viewer. Two large laminate panels designed by Perry Roberts add further colour and pattern in the entrances.

Working with the architects, Roberts also devised supergraphics, which link with all the other art elements in the building and support wayfinding. As artists in residence, ArtNucleus photographers Simon Ryder and Reinhild Beuther were each assigned to a building, and they worked with staff to create a series of images that capture moments of change and transition; these are now installed in the building as an enduring record of the buildings and their occupants’ narratives.

Client: North Bristol NHS Trust

Architects: Avanti Architects,

Art Consultants: Willis Newson

Completion: 2010

Contract: ProCure 21

Artists: Kate Blee, Perry Roberts, ArtNucleus

Construction: Laing O’Rourke

Engineering: Design Buro

Poncelet’s interventions are more strategic in creating atmosphere and assisting wayfinding. She played a major role in the choice of colours, which give the building its lively and appealing character. From the outside, sky-blue brise soleil contrast with the dove-grey brick, as do the vivid green, yellow and red painted elements delineating each void both outside and in. The same calming sky blue is used on blinds in consultation rooms. Poncelet devised a large and colourful tapestry of enameled, magnetic panels for the reception area. Posters and information for parents are displayed on these panels at eye level for adults, while there are more playful items in varied colours and shapes at knee level for children. Poncelet also came up with a decorative motif inspired by the brickwork, which emerges as a coloured stitching whether it’s inlaid into the entrance path as a tile carpet, or replicated on a metal kickplate at the bottom of the doors; the doors themselves are painted in the similar or softer shades of the key palette and some are surrounded by tiny enamel tiles at varying heights, scattered among the consulting rooms, to help with exploration and identification. Says AHMM associate Thomas Gardiner: “Jacqui’s idea was that every time a child comes in here, they will find something different.”

Matthew Turner, a child-support worker who has been at Sunshine House since it opened, says: “The art work is really brilliant; we noticed it at first with the visually impaired, with the raised lettering on the glass panels. We have children who come here from birth to 19 and they always return to a particular piece of glass. We see parents engaging with the kids over the lettering – they start going through the alphabet or playing word games with them.

“With a breeze, the entrance sculpture goes spinning around and we can see, if a child reacts to it, that they obviously have perceptual skills. We also get a lot of feedback from pediatricians. The way the child reacts to the environment tells them a lot about the degree of perception they have – even before they’ve got to the assessment rooms. The coloured doors and tiles make a huge difference, too. We can test their recognition and independence by sending them to different coloured areas.”

Despite being five years old, and with a complex variety of elements and surfaces, the building looks in great condition. Turner agrees its popularity helps with maintenance. He says: “We had the infection-prevention control team inspect us recently and they said the building could be brand new – it’s so clean. People like it so much they really look after it.”

Though there may be less glory in weaving humanising elements throughout a building than in creating big, spectacular artworks, ideally, there should be scope for both, argues Poncelet: “As an artist, It is your job to bring your experience, insight and wisdom as a human being and use that to inform your art.”

North Middlesex University Hospital, UK North Middlesex University Hospital, UK

Consultation is an art in its own right, according to artist Sue Ridge, who worked with poet John Davies (aka Shedman) to help generate community engagement and interest around the new North Middlesex University Hospital (NMUH), a £123m PFI-funded hospital. The aim was to use the lift lobbies around its four-storey main atrium, plus the hospital waiting areas, as a canvas for whatever poetic and visual work resulted. Architects Nightingale Associates had already conducted research into the area’s history, unearthing links with the poet John Keats (who lived and went to school nearby) as well as other literary figures. This inspired the idea of creating a collaborative community ‘poetry wall’ using digitally printed ‘social wallpaper’, plus a series of five photo-text images for hospital waiting areas.

Consultation began via Davies’s portable shed, placed by the main restaurant, where opinions and feedback were sought from staff, visitors and patients, through interviews and creative-writing workshops. Davies and Ridge transformed the resulting conversations and compositions into the aforementioned ‘digital social wallpaper’.

In the meantime, Ridge was inspired by a Michael Rosen poem, called ‘These are the Hands’, which celebrated the 60th anniversary of the founding of the NHS; she decided to photograph members of staff with open hands, collecting their names and informal descriptions of their jobs to frame and use in conjunction with the social wallpaper. The poetic and visual collage, weaves together the narratives of an extremely diverse community (with 147 different languages spoken in local schools) against the weft of local historical anecdotes, both ancient and modern. Says Ridge: “We wanted to convert the community’s stories into ‘our stories’, helping people make the new hospital their own.”

Client: North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust

Architects: Nightingale Associates

Art consultants: First Aid Art

Artists: Sue Ridge and John Davies

Construction cost: £123m

Conclusion

Reviewing recent art in healthcare projects, Susan Francis, founder member and programme director for Architects for Health, senses that real progress has been achieved. But she is worried that this is the result of schemes commissioned and budgeted for under very different financial and political circumstances. With many fine healthcare architects currently struggling to stay afloat and hospital closures threatened, she foresees tough times ahead. Stressing that “art and landscaping are always the most vulnerable areas”, she concludes: “It would be tragic if we lost the quality and expertise that we’ve developed so far.”

Veronica Simpson is an architectural writer

|

1.1.jpg)

|