Inpatient Unit Flexibility: Design characteristics of a successful flexible unit

This study looks at flexibility in healthcare design from the perspective of the end user and how the physical design of a facility impacts on both staff and service delivery.

Debajyoti Pati, PhD, FIIA, LEED AP, Thomas E Harvey Jr, AIA, MPH, FACHA, LEED AP

Flexibility in healthcare design is typically addressed from an architectural perspective without a systematic understanding of its meaning from the viewpoint of the end user. Moreover, the architectural perspective has generally focused on expandability and convertibility. This study explored fl exibility needs in adult medical-surgical inpatient care with the aim of understanding its meaning from an end-user perspective, as well as identifying the characteristics in the physical environment that promote or impede stakeholders’ requirements. We used a qualitative design and conducted semi-structured interviews with 48 stakeholders in nursing and nursing-support services at six hospitals across the US.

Data was collected from September to November 2006. The findings suggest that adaptability influences more aspects of unit operations than convertibility or expandability. Furthermore, physical design characteristics impact on nine critical operational issues where flexibility is required, spanning nursing, environmental services, materials management, dietary services, pharmacy and respiratory therapy.

Introduction

Discussions in healthcare literature on flexibility are few and far between. However, substantial thought is available with regard to retail and workplace settings. Notable is the historical demand for change arising from such factors as technology, finance, and fashion1, and a layer-based structured approach to building flexibility2.

Recent healthcare literature reflects similar thoughts. One thesis infuses flexibility in by fragmenting the design into three systems based on service life3. In addition, the necessity and available opportunities to infuse flexibility into design in order to address future expansion needs, changes in operational trends and advancements in technological and clinical practices, among others, have recently been presented by a few healthcare practitioners4,5.

Almost all discussions on flexibility in healthcare design, however, have occurred at the overall hospital level. Flexibility issues at the inpatient unit level have not been widely published, other than those occasionally arising from clinical process challenges, such as the universal patient room6, and distributed nurse station and supplies7.

Understanding flexibility needs at the inpatient unit level is currently assuming considerable importance. Healthcare is going through one of the most challenging phases in history, including an ageing America8, rising acuity levels9, workforce shortages and ageing nurses10,11, and staff dissatisfaction and turnover12. Rapid technological developments are changing patient care delivery processes.

In addition, patient safety issues have emerged as a major concern13,14. Hospitals continually respond to such changes in internal and external factors by implementing changes in unit operational models15.

The physical design of a setting either facilitates or impedes the implementation of such changes over the life of a hospital. Designs that impede changes can lead to expensive renovation work during the life of a facility, to the premature obsolescence of a facility or, all too often, to the development of care-giving plan that is suboptimal because it is designed around the constraints of the facility. In addition, the physical design of facilities could infl uence staff effectiveness16.

From the viewpoints of efficiency, staff well-being and lifecycle cost, it is essential that the built environment supports different unit operational models over a facility’s lifetime.

Moreover, with a substantial proportion of the current massive investments in healthcare facilities going into bed tower constructions, (US$16-$20bn over the next decade17) comprehending the flexibility issues of inpatient units has wide implications and immediate practical utility.

The questions

We approached the study with an exploratory emphasis but within the adaptability, convertibility and expandability framework. It was apparent that articulating flexibility needs was contingent on the comprehension of flexibility in inpatient care.

As a result, knowledge of the meaning of flexibility from the viewpoint of the different stakeholders in the care delivery process constituted a prerequisite to investigating the design implications. We approached the problem with three

main questions:

1. What does flexibility mean to different stakeholders of care delivery on inpatient care units?

2. What physical design variables do stakeholders identify as the critical dimensions of unit architecture that influence their flexibility?

3. What characteristics of inpatient care unit architecture promote or hinder flexibility?

Method

We focused on adult medical-surgical inpatient units since such units are the most common inpatient units across all hospital types and thus enhance the wider applicability of the findings of the study. The authors conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with management, nursing and support staff at six hospitals across the US. In total, 48 interviews were conducted. Table 1 lists the number of respondents and their departmental affiliation in each hospital.

All six hospitals are new constructions, completed within the past decade. The hospitals were selected through a purposive sampling to maximise variations in physical attributes, including hospital size, unit size, unit shape, circulation type and geographical location (Table 2).

At each hospital, participation was solicited from stakeholders in patient care services, including nursing, respiratory therapy, dietary services, environmental services, materials management and pharmacy. Two research team members interviewed the volunteering participants individually for one hour on site. Interviews were conducted between September and November 2006 and guided by a plan of inquiry prepared and tested before the site visits.

The plan of inquiry included questions that addressed six main areas:

• description of a typical day on the unit by the interviewee;

• challenges the interviewee faced in conducting tasks efficiently;

• things that contributed to operating efficiency and those that the interviewee would like to change to improve efficiency;

• areas on the unit that had been changed since occupation;

• reflections on how things might change in the future and aspects of the physical design that would need to be changed; and

• the interviewee’s interpretation/s of the term ‘flexibility’.

The plan of inquiry was pre-tested using a combination of field testing and cognitive pre-testing methods18. All interviews were tape-recorded for accuracy and transcribed verbatim for subsequent analyses. Interview transcripts were subjected to content analyses19 with three main objectives:

• to identify varying interpretations of the term ‘flexibility’;

• to understand the relationships between interpretations of flexibility and descriptions of functional efficiencies; and

• to identify attributes of the physical environment that facilitate or impede functional efficiencies.

|

Figure 1: Corner location of nurse station at Laredo Medical Center ensures enhanced peer lines of sight

|

What does ‘flexibility’ mean?

In general, stakeholders of inpatient units view flexibility purely in operational terms, while managers and administrators view flexibility at the global level of patient care management, resource allocation and response to population census. Direct caregivers view flexibility as an individual-level response to changing demands.

Most responses focused on being able to provide optimum service to patients, or to the direct caregivers, and fell within the domain of operational flexibility. Table 3 summarises the meaning different stakeholder groups attached to flexibility and the associated physical design variables.

Physical design and flexibility

Nine different flexibility needs were identified as being impacted by physical design decisions. Seven of the nine were associated with adaptability and one each was associated with convertibility and expandability.

There are some important and subtle differences between the healthcare definitions of adaptability and convertibility from those used in workplace literature. Flexibility to adapt (or ‘adaptability’) is defined as the ability to adapt the environment to new circumstances, without making any change in the environment itself.

Flexibility to convert (or ‘convertibility’) is defined as the ability to convert the environment to new uses, with a simple and/or inexpensive alteration to the physical environment20.

Flexibility to adapt

Data analyses suggest seven areas pertaining to adaptability that have physical design implications: peer line of sight, patient visibility, multiple division/zoning options, proximity of support, resilience to move/relocate/interchange units, ease of movement between units and departments, and multiple administrative control and service expansion options. Two concepts that did not surface in the interview transcripts were single-patient rooms and universal rooms.

Peer lines of sight

Operational issue: It is frequently envisioned that nurses work independently in providing care to their assigned patients. In contrast, the teaming of caregivers constitutes a major managerial decision. While nurses are generally assigned to a group of patients to whom they are primarily responsible, many situations in the caregiving process demand helping hands.

Teaming nurses helps optimise care during such situations – which is frequent owing to the uncertainties that characterise the healthcare environment. Teaming nurses has more than just instrumental implications. It helps develop social networks, mentoring and stress mitigation in a high-stress work environment.

A key factor influencing effective teaming is peer lines of sight. Direct visibility of peers enhances efficiency and provides a sense of safety and security for caregivers. Obstructed peer lines of sight increase stress by reducing the perceived and actual availability of help, the opportunity for mentoring and socialisation, and the potential for de-stressing. Moreover, in crisis or stressful situations, clinical staff revert to their senses rather than technology, enforcing the importance of peer visibility.

Stress levels increase and perceptions of flexibility decrease when nurses feel they are operating alone. The above factors could impede or improve one’s ability to be flexible to new or unique situations, and constitute an issue affecting direct caregivers. This issue was reflected in the responses of six (of 11) nurses in five hospitals and two (of six) respiratory therapists in two hospitals.

Environmental correlates: Contemporary practice in healthcare design is to shift the principal work zones of the caregiver closer to the patient by placing documentation areas and supplies storage closer to patient rooms. This is essential to minimising travel distances and increasing direct care time available to patients. However, the design of these work areas is critical to the nurses’ sense of flexibility. Embedding these work areas too deeply out of the line of sight down corridors, or in areas comprising blind corners off of the racetrack of circulation, creates line-of-sight obstructions.

Of particular interest to designers is the feedback from several caregivers that the gently curving corridors, often designed to give elegant exterior form and to minimise the perception of corridor length in the interior, was an impediment to desired visibility throughout the unit.

Implications for inpatient unit design: Data suggests that several design characteristics improve peer visibility: simply shaped unit configurations that permit as much distal visibility as possible; the corner locations of any caregiver workstations within the support core (Figure 1); and backstage corridors linking caregiver stations that may be designed within the core space.

On the other hand, several design characteristics create potential obstructions to peer lines of sight, including: double loaded corridors of patient rooms extending off and beyond a racetrack confi guration; curvilinear corridor configurations (particularly with the dramatic increase in size of today’s patient rooms); charting alcoves that are so deep that sight lines are lost; and opaque support cores that obstruct visibility across a unit.

Patient visibility

Operational issue: Higher acuity in medical-surgical units is necessitating direct sensory (sight and hearing) links to patient rooms – a factor that has considerable impact on one’s flexibility to multi-task. In addition, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) National Patient Safety Goal No. 6b21 requires that nurses, respiratory therapists and other staff be able to hear equipment alarms from a satellite or central workstation. However, nursing assignment frequently involves non-contiguous patient rooms where sensory links could be potentially obstructed.

It is conventionally believed that direct patient visibility is important only in intensive care environments. However, the rise in the acuity level of today’s medical-surgical inpatient population, as well as increasing efforts to reduce accidents and the risk of falls, has resulted in an imperative for the nurse to have improved visibility and auditory connection with the patient room. This includes greater visibility of the patient from the corridor. The ability to, at a minimum, see the patient room door from the main or sub-workstation provides the nurse with the proximity to hear activity in the room as well as see the patient room door. Patient visibility affects staffi ng effi ciency as well as caregiver efficiency. This issue was reflected in the responses of 10 (of 17) nurses and nurse administrators in six hospitals, and two (of six) respiratory therapists in two hospitals.

Environmental correlates: The location of patient rooms in relation to caregiver workstations, medication stations and utility room doorways is the key physical design factor influencing patient visibility.

Implications for inpatient unit design: Data suggests that several design characteristics aid in patient visibility, including: multiple caregiver work centres with proximal patient room locations, so that shifts with fewer staff who may congregate periodically can still keep an eye (and ear) on the unit territory; unobstructed lines of sight between nurse work zones and patient room doors; and outboard location of patient room toilet/shower rooms (Figure 2).

Multiple division/zoning options

Operational issue: Optimising staffing constitutes a major component of departmental operations and a balanced and effective allocation of responsibilities remains at the heart of staffing. While it is typically believed that nurses are assigned to a set of contiguous patient rooms, in reality the assignment of patients to nurses is based on a number of objective and subjective criteria.

The major considerations include the acuity level of the patient (the severity of patient’s condition), the competency of a nurse, a safe nurse/patient ratio and the ability for one to have convenient access to all patients assigned. Based on balancing these criteria, the actual assignment of patients may not result in contiguous rooms.

Any perceived barriers between patient rooms may either preclude assignments or create a stressful sense of overload, leading to a set of perceived undesirable rooms.

Such factors could impede the flexibility of the nurse manager to arrive at a balanced assignment of nurses to patients (or the flexibility in zoning and rezoning patient rooms in response to census) and address uncertainties in patient census. This issue was reflected in the responses of 10 (of 17) nurses and nurse administrators in five hospitals.

Environmental correlates: Among the factors contributing to perceived barriers and potentially undesirable rooms are stairwells interspersed with patient rooms, support spaces located between patient rooms and staff toilets located between patient rooms.

Even smoke compartment door locations within the unit can contribute to the perception of an increase in walking distances and a decrease in visibility.

Implication for inpatient unit design: Data suggests several design characteristics that reduce perceived barriers, including stairwells or support spaces at the ends of arrays of patient rooms, and stairwells or support spaces within the support core. On the other hand, patient rooms that lie outside the primary circulation of a floor plan (for instance patient rooms located off of the main circulation in a racetrack confi guration) contribute to perceived barriers, in addition to creating added walking distance to and from these areas to support spaces.

|

Figure 2: Bon Secours St Francis Hospital in Charleston, South Carolina, with its unique pod design and outboard toilets offers patient visibility through satellite nursing stations located close to the patient room

|

Proximity of support

Operational issue: Perceived and actual undue walking distance constitutes one of the predominant factors affecting flexibility. Undue walking distance results in higher stress and fatigue, thereby reducing one’s ability to react to unusual circumstances and to be able to multi-task effectively. This issue affects both nursing and support staff. It was reflected in the responses of 12 (of 17) nurses and nurse administrators in six hospitals, four (of seven) environmental services respondents in four hospitals, two (of six) dietary services respondents in two hospitals, three (of six) materials management personnel in three hospitals, and three (of six) respiratory therapists in three hospitals.

Environmental correlates: Besides patient room to patient room circulation, a major contributor to staff walking is the distance between assigned rooms and nursing support spaces. The potential to reduce walking distance, through the provision of built-in cabinets or mobile carts in patient rooms or allowing storage capacity outside or inside the room, frequently encounters operating challenges pertaining to inventory management, control, rotation and charge capture, and re-stocking responsibility. As a result, trips to the service core for support provisions are typical in the industry.

Access to medications is yet another issue contributing to walking and fatigue. Departmental control of space, staffi ng and equipment costs still drive this equation. Continued centralisation of one to two rooms on a floor for medications and supplies perpetuates extensive walking distances and time in nonproductive activity. In addition, remotely located centralised storage rooms for frequently used medical equipment also contributes to increased travel distances.

Implications for inpatient unit design: Data suggests that several physical design characteristics contribute positively to flexibility by minimising walking distances. Such characteristics include: simply-shaped, possibly symmetrical units with the core location of support provisions that are as distributed as possible; association of these distributed supply areas with the caregiver work stations, whether at bedside, room-side, or team work areas in the core; and provision of decentralised room-side supply cabinets (also known as nurse servers).

Resilience to move/relocation/interchange units

Operational issue: The ability to move services across floors or units, or both, enhances the efficiency and flexibility of

operation, especially since sustained long-term census fluctuation is a rule rather than an exception. It allows the occasional shuffling of services (Figure 3) to arrive at the best fit between services and physical units. It was reflected in the responses of five (of 17) nurses and nurse administrators in three hospitals.

Environmental correlates: A standardised unit – where patient rooms as well as the support core are standardised – is a necessity before the physical design can significantly enhance the flexibility to move or relocate.

Implications for inpatient unit design: Standardisation is the reverse of customisation. As a result, standardisation to accommodate multiple types of patient populations will need additional resources during design. More importantly, standardisation should not be considered solely at the patient room level. Designs of support core change, depending on patient population type and standardisation of the support core, are essential for accommodating different patient populations over time without compromising efficiency. Standardisation should be viewed distinctly from the concept of universal rooms. A standardised unit may or may not comprise universal rooms.

Ease of movement between units and departments

Operational issue: Hospital personnel responsible for multiple units within the hospital are required to travel to several areas in a time-efficient manner. Inefficient, obstructed or long circulation routes significantly affect stress and fatigue and, thus, one’s flexibility to address changing situations.

This issue is more critical for ancillary caregivers, physicians, support personnel and nurse managers than the general floor nurse. The need to cross over between units is high among these stakeholders. It was reflected in the responses of four (of 11) nurses in three hospitals, two (of seven) environmental services respondents in two hospitals, two (of six) dietary services respondents in two hospitals, one (of six) materials management personnel in one hospital, two (of six) pharmacists in two hospitals and five (of six) respiratory therapists in five hospitals.

Environmental correlates: The provision of direct, easy circulation between units – vertically and horizontally – strongly facilitates flexibility.

Implications for inpatient unit design: Strong consideration should be given, in programming and design, to provide a central circulating stair linking fl oors of a bed tower, regardless of whether or not it serves a life-safety egress function. It is more important to simply facilitate an easy, quick run up or down the stairs to go to another floor rather than wait on elevators for routine or Code Blue procedures. Proximal location of vertical circulation core, back corridor links between units and communicating stairs linking vertically-stacked units are examples of design that enhance flexibility.

|

Figure 3: Standardised rooms in Clarian West Medical Center made ICU room allocation changes more economical

|

Multiple administrative control and service expansion options

Operational issues: A frequent challenge faced by management is dealing with uncertainties. The most exemplary case of uncertainty is a sudden, unexpected and sustained increase in census, thus leading to the resizing of a service. Since uncertainties affect the match between expectations and reality, it could lead to a significant impact on job satisfaction and performance. Apparently census fluctuations in large units could exert unexpected pressure on available staff, in contrast to smaller units where it is easier to absorb additional population without adverse impact on caregivers. Across all the cases studied, census estimates – total, as well as in particular population groups – during a hospital’s planning and procurement changed considerably once the facilities were occupied.

As a result, services experiencing larger demand are expanded in size, frequently spreading into adjoining units. This issue could affect the flexibility of unit management in optimising staffing and was reflected in the responses of seven (of 17) nurses and administrators in five hospitals.

Environmental correlates: Space programming and design solutions for bed units that allow the floor to be subdivided in some way will contribute to more flexibility from a patient care management and administration perspective. Mixing services on a nursing floor can contribute to confusion and patient assignment challenges. The ability to identify sub-zones of care within a floor may help meet this need which is often related to fluctuations, both short- and long- term, in census with services. This concept can be addressed either in the proposed size of the basic bed unit or in design configurations that allow sub-zoning without contributing to visibility and assignment issues.

Designing similar unit plans in an adjacent position on the same floor appears to be highly beneficial in enhancing flexibility. However, this contiguity is only beneficial where the linkage is through a non-public corridor connection. Such an arrangement, if sufficiently close, can allow an occasional swing of patient load between the units and better support a longer-term growth in census within a specific service (Figure 4).

Implications for inpatient unit design: Design characteristics that enhance service expansion options include back corridor links between horizontally adjacent units and the ability to create sub-zones of patient services within a unit perceived by staff to be their zone (visual or geographic cues). During design, it is prudent to assess the impact of patient care services spread over multiple floors on nursing management’s ability to lead and supervise as necessary.

Flexibility to convert

Within the realm of inpatient unit flexibility to convert, one issue surfaced in relation to physical design: adjustable support core elements. A frequently advocated design concept in industry literature – the acuity adaptable room22 – did not surface in the discussions.

Adjustable support core elements

Operational issue: There is a more than occasional need for adjustment in the use of support core space arising from changes in operations, equipment and management. Supply storage room design occasionally needs re-thinking due to changes in inventory management systems and, more often, supply packaging. The size, shape and quantity of consumable goods, reprocessible items and portable medical equipment to be centrally held on a bed unit change on a regular basis. As a result, support core space demands frequent modifications. It was reflected in the responses of 13 (of 17) nurses and administrators in six hospitals, seven (of seven) environmental services respondents in six hospitals, one (of six) dietary services respondents in one hospital, five (of six) materials management personnel in five hospitals, four (of six) pharmacists in four hospitals, and four (of six) respiratory therapists in four hospitals.

Environmental correlates: Built-in cabinetry offers limited flexibility and adaptability. In fact, units intending to create more lean processes have removed doors from built-in cabinetry to eliminate door swinging. Further, with changes in equipment design over time, there is a constant need for adjusting room shapes and sizes in the support core.

Implications for inpatient unit design: In basic supply holding areas – such as clean and soiled utility rooms and equipment holding rooms – modular, moveable compartments or cart systems offer adaptability and the benefit of easy removal for thorough periodic cleaning. Similarly, for the material holding areas of medication and nourishment rooms, the same modular, moveable systems would effectively address the need. The cost of these systems compared to built-in and enclosed solutions is often considered a barrier.

However, given the modular systems’ ease of responsiveness to long-term changes, this cost could be justifiable. Further, design efforts that minimise walls containing mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) elements to more easily permit partition relocation should be explored.

Flexibility to expand

One issue surfaced in relation to expandability which is, nevertheless, a vital issue in enhancing long-term inpatient unit flexibility.

Expandable support core

Operational issue: Over time, operational changes demand more space in the support core – for example, when services like respiratory therapy and pharmacy are decentralised and moved to the inpatient units. The ability to expand the support core over time could considerably enhance operational effi ciency over the long run. This issue was reflected in the responses of 10 (of 17) nurses and administrators in six hospitals, seven (of seven) environmental services respondents in six hospitals, one (of six) dietary services respondents in one hospital, four (of six) materials management personnel in four hospitals, three (of six) pharmacists in three hospitals, and three (of six) respiratory therapists in three hospitals.

Environmental correlates: The availability of space to expand support core functions adjacent or close to the unit is warranted for long-term flexibility. In the short run, it could take the form of a hotel-type unassigned space on each floor of the unit. This space offers two distinct points of fl exibility. First, it can accommodate a specialty support function associated with the clinical service assigned to that floor – for example, a physical therapy satellite for an orthopaedic unit or a satellite pharmacy area on an oncology unit. Second, it can serve as an equipment or technology garage to centrally hold many of the necessary support tools used infrequently on today’s inpatient care units, such as bariatric chairs or beds or patient lifts. In the long-term, areas in the support core needing additional space could replace the hotel-type function.

Implications for inpatient unit design: In response to the need for expansion, the following considerations could help enhance unit flexibility:

• designing adjoining spaces that can serve as an extension of support core space, which is highly useful for shared support elements between units (Figure 4); and

• provision of a ‘loose’ programme approach of unassigned space which will typically find an appropriate use before schematic design is complete.

Care should be taken to ensure adherence to the real storage needs on inpatient floors when budgets get tight and space is cut. A balance between bed numbers and storage space must be maintained to make certain that the resultant design offers the required storage space for equipment.

Better anticipation and programming for the inevitability of service and operational changes could help in promoting a flexible unit design.

|

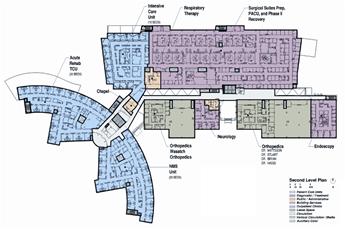

Figure 4: The layout of MacKay-Dee Hospital facilitates ease of movement between units and service expansion

|

Discussion

The most noteworthy aspect of the findings pertains to the differences in the number of operational issues related to the three facets of flexibility at the inpatient unit level. Specifically, seven of the nine flexibility issues relate to adaptability, far outnumbering the operational issues affected by the flexibility to convert and expand.

In contrast, previous healthcare and workplace literature has predominantly focused on expandability and convertibility – and a vast majority of flexibility considerations during hospital design also occurs in the realm of expandability and convertibility.

Our findings suggest that the nature of flexibility required could change depending on the specific setting. In addition, adaptability considerations for inpatient care units should be accorded higher, or at least equal, priority to expandability and convertibility.

As a result, for designers of inpatient units, adaptability is a vital area to ensure short- and long-term operational efficiency (without de-emphasising the importance of support core convertibility and expandability). Data analyses suggest that physical design plays a crucial role in facilitating or impeding the ability of organisations and their personnel to adapt to changing workload demands, staffing patterns and operational challenges. Adaptability is also crucial to long-term flexibility in inpatient care. Irrespective of changes in technology, operational design, philosophy of service and models of care, several things will remain constant over time in care-giving.

Patient care will be primarily given by one or more nursing staff to a patient; some form of a care-giving team will be assigned a group of patients; and maximising time spent at the bedside in direct patient care activities will be a high priority for design. It is also likely, regardless of advances in technologies and care delivery models (such as video monitoring and eICUs), that geographic zoning of the inpatient care unit will continue to be an operational consideration, in order to find a best-practice balance between cost of space, equipment, support human resources for care and the maximisation of direct care by the nurse.

What may change is the way support services, such as medication, supply and food, are delivered to care-giving teams; how sanitation and infection control standards are met; how all forms of communication are facilitated between all parties to the care experience; and how non-patient parties are assimilated into the care plan and care environment.

Considering the projected shortage of trained nurses, as well as other allied caregiver personnel, it is possible that the need for care-giving staff to be multi-skilled and able to be flexible and adapt to changing situations and demands may increase over the next decades. From such a perspective, adaptability assumes considerable importance in the short as well as the long term.

The primary emphasis of this study was to articulate the flexibility needs of care-giving staff to designers, as well as to address ways to enhance the ability of the physical environment to support the functional needs of caregivers over the long run. This study constitutes a preliminary but important step in that direction.

This study is essentially exploratory in nature and, hence, should be considered with an appropriate understanding of these limitations. Consistent with most qualitative study designs, the sample size was intentionally kept small. Future studies should consider expanding the sample for greater generalisability, as well as more explanatory assessments of design characteristics and flexibility in inpatient care units, based on the findings from this study. In addition, bed unit operations are not entirely insulated from the flexibility needs of the rest of the hospital.

Future studies could and should begin to link micro and macro fl exibility needs and the design issues arising out of such needs. Nevertheless, this paper constitutes a unique and important contribution to our understanding of flexibility in architectural design for inpatient care units.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the American Institute of Architects research grant and the financial support provided by Herman Miller that made this study possible. (Pati D, Harvey T, Cason C. Environment and Behavior 2008; 40(2):205-232. Reprinted by permission of Sage Publications.)

Authors

Debajyoti Pati, PhD, FIIA, LEED AP is director of research at HKS Architects.

Thomas E Harvey Jr, AIA, MPH, FACHA, LEED AP is senior vice president of HKS Architects.

References

1. Duffy F, Hutton L. Responding to change. Architectural knowledge: The idea of a profession. London and New York: E & FN Spon; 1998. Brand S. How buildings learn: What happens after they are built. New York: Penguin; 1995. These two publications are particularly noteworthy. To enhance flexibility to adapt to changing business practices or to convert a building to a different occupancy type, a classification structure of building systems was proposed based on control, system life, and resilience to change. Four shearing layers were defi ned: shell (structure), service (cabling, lifts), scenery (partitions), and set (furniture).

2. Brand (1995) expanded this structure to include: site, structure, skin, services, space plan (interior layout) and stuff (furniture). It was asserted that designing resilience between the layers from the very beginning would enhance the flexibility to adapt or convert at a later stage in a building’s life.

3. Kendall SH. Open building: A new paradigm in hospital architecture. AIA Academy Journal (7th ed) 2004; 22-27. The open building paradigm layers building systems into: primary system (nearly 100 years; building envelope, structure), secondary system (nearly 20 years; interior walls, floor covering, ceiling) and tertiary system (nearly 5-10 years; furniture, mechanical equipment, hospital supply). Implemented in the Insel teaching-hospital campus in Bern, Switzerland, it is argued that the separation of the systems will ensure independence of the lower-level system/s from the higher level system/s, affording flexibility to changes while minimising construction.

4. Chefurka T, Nesdoly F, Christie J. Concepts in flexibility in healthcare facility planning, design, and construction. Academy Journal 2005. Retrieved 19 February 2006 from http://www.aia.org/aah_a_jrnl_0401_article6

5. Varawalla H. Designing for fl exibility building in order and direction for growth and change. Express Healthcare Management 2004. Retrieved 20 November 2006, from http://www.expresshealthcaremgmt.com/20040831/ architecture01.shtml

6. Altemeyer, DB, Buerger TM, Hendrich, AL, Fay JL. Designing for a new model of healthcare delivery [Electronic version]. Academy Journal 1999; 2(2). Hendrich A, Fay J, Sorrels AK. Effects of acuity-adaptable rooms on fl ow of patients and delivery of care. American Journal of Critical Care 2004; 13(1):35-45. Matukaitis J, Stillman P, Wykpisz E, Ewen E. Appropriate admissions to the appropriate unit: A decision tree approach. American Journal of Medical Quality 2005; 20(2):90-97. Brown K, Gallant D. Impacting patient outcomes through design: Acuity adaptable care/universal room design. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 2006; 29(4):326-341. Universal room (an inpatient room intended to accommodate patients at all levels of acuity) and the variable acuity nursing model (a nursing model of care designed to serve a patient population at all levels of acuity, from acute care to step-down to intensive care) have been propounded as innovative solutions to enhance flexibility. Originating with the desire to reduce patient transfers between units corresponding to changes in acuity level, universal rooms and the variable acuity nursing model have gained popularity owing to the assertion that those concepts offer latitude in patient allocation, staffing (assignment of nursing staff to patients in a particular care delivery model), and long-term adaptability to changes in patient population, acuity, and census.

7. Rashid M. A decade of adult intensive care unit design: a study of the physical design features of the best-practice examples. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 2006; 29(4):282-311. Another aspect of inpatient unit design covered in recent literature pertains to the flexibility afforded by distributed nurse stations and supply (Rashid includes a comprehensive description of nurse station options in the context of intensive care units).

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Projected supply, demand, and shortages of registered nurses: 2000-2020. July 2002. Retrieved 19 February 2006 from http://www.ahca.org/research/rnsupply_demand.pdf

9. Stanton MW. Hospital nurse staffi ng and quality of care: Research in action (14). Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004.

10. Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI. Implications of an aging registered nurse workforce. Journal of the American Medical Association 2000; 283:2948-54.

11. Janiszewski GH. The nursing shortage in the United States of America: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2003; 43(4):335-343.

12. Andrews D S. The nurse manager: job satisfaction, the nursing shortage and retention. Journal of Nursing Management 2005; 13(4):286-295.

13. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Institute of Medicine Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1999.

14. Page A. Keeping patients safe: transforming the work environment of nurses. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

15. A holistic patient care delivery design, which situates nursing care within a larger framework that includes personnel from support service departments.

16. Berry LL, Parker D, Coile RC Jr, Hamilton DK, O’Neill DD, Sadler BL. Can better buildings improve care and increase your financial returns? Frontiers of Health Services Management 2004; 21:3-24.

17. Ulrich R, Zimring C, Quan X, Joseph A. The role of the physical environment in the hospital of the 21st century: A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The Center for Health Design; 2004. Retrieved 20 April 2006 from http://www.healthdesign.org/research/reports/physical_environ.php

18. Krosnick JA. Survey research. Annual Review of Psychology 1999; 50:537-567.

19. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications; 1994. Data analyses followed the steps suggested by Miles and Huberman.

20. Hamilton K. Design for flexibility in critical care. In K Hamilton (ed), ICU 2010: ICU design for the future. Houston: Center for Innovation in Health Facilities; 2000.

21. Joint Commission Resources. JCAHO national patient safety goals: Practical strategies and helpful solutions for meeting these goals. 2004. Retrieved 3 September 2007 from http://www.jcrinc.com/5308

22. Patient rooms designed to be upgraded to a higher acuity level with minor renovation, in a relatively short period of time.

|

1.1.jpg)

|