Designing Healthy Communities: The Health Impact of Street Vendor Environments

|

|

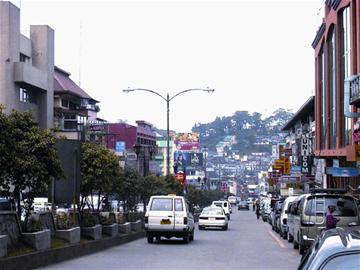

Typical female street vendors in Baguio City, out in the open, exposed to traffic pollution, weather and disease

|

This study, spanning seven years, reveals how the informal architecture of the environments, in which street vendors ply their wares in countries like the Philippines, impacts on their health.

The built environment plays a powerful role in the health of a population. Its influence has been documented in numerous studies, ranging from urban sprawl and its impact on obesity, diabetes and poor nutrition to highway development and the increase in pedestrian injury, and the impact of nature deprivation on low mental health and well-being. However, many of the existing studies have not used comprehensive research designs and methods; they lack multiple study points in time; and they have not interviewed respondents in situ.

This study contributes a perspective of design and health that goes beyond designing healthcare facilities for patients who are already diagnosed with health problems. It unveils a different world of people who work in busy, often chaotic, and noisy urban streets. Their environments are temporary, marginal, uncertain and fluid.

Such informal architecture is found in urban places all over the world1. In this context, it involves viewing the built environment within a framework that includes street people’s cultural lifestyles, socio-economic values and spatial behaviour.

Baguio City street vendors

This study comprises a longitudinal and transdisciplinary study of street vendors in Baguio City in the Philippines. It is a fast-growing regional centre for higher education, medical services, business opportunities and tourism. Situated in the rugged upland region of the Cordillera Mountains, the city was planned for 50,000 people but now holds about 250,000 residents. Lack of official jobs and the economic downturn of many global cities have driven residents to legitimately earn a living on urban streets.

Street vendors create spaces within existing buildings, sidewalks and streets to establish their ‘territories’ and sell their products. The result is a tapestry of informal architecture set on the existing built-environment infrastructure. The question is: “How does the architecture impact on street vendors’ health?”

Literature on the health of street vendors has focused largely on studies related to public safety and food-borne diseases. Other research projects have examined vendor health in terms of pollutant contamination in their bodies and reproductive conditions2,3,4.

These studies generally imply that vendors’ presence in the streets for long periods of time poses an occupational health hazard. However, to date, no study has delved into the physical environment – the architecture and land-form features – and its contribution to the health conditions of vendors. Furthermore, design guidelines to mitigate their health circumstances have not been addressed. This paper hopes to lessen this gap in the literature.

The study involved multiple research methods from 1999 to 2006. Table 1 describes the various research phases of the project. The methods ranged from personal surveys and physical place assessments to health screening procedures.

This eclectic use of research techniques has contributed to a comprehensive understanding of vendors and the impact of the street environments on their health. Throughout the seven-year duration of the research project, two surveys were conducted – one in 1999 and the other in 2003 – with samples of 219 and 187 respondents, respectively. Many of these individuals were repeat respondents. Generally, the characteristics of the vendors are the following:

• At least 80% are women in their early 40s

• They have an average of four children.

• At least 50% have a high school education

• The majority of respondents have stayed in the same vending locations between seven and 11 years. Vendors choose to engage in this type of street occupation

• They work long hours – 10 hours a day, Monday to Sunday – and earn only about US$20 a week.

The research site Baguio City’s central business district is situated in a deep valley with four arterial streets leading to it. In the early 1900s the location was selected by the American colonialists as a resting and healing place for their troops.

Documents written by military physicians have chronicled the positive impact of this upland city on soldiers’ health because of its high elevation and cool air. From a quiet convalescent place, Baguio City transformed throughout the centuries into a busy economic engine for the region.

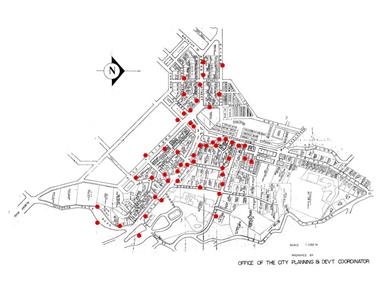

At the initial phase of this longitudinal study, the vendor spaces were measured, together with sidewalk widths and other physical attributes. The space metrics show that 44% of vendors are located in relatively flat areas and 56% are sited on steep inclines5.

Topography is an important factor in the entrapment of air pollution, which in turn affects health conditions. Another significant feature of the central business district is the high traffic volume that has exceeded its streets’ carrying capacity.

Major colleges and universities, government offices, as well as the city market, are magnets that draw people and diesel-run vehicles to its centre. Idling vehicles in the land basin and those running uphill on steep inclines contribute to the mix of polluted air and noise.

Also important to this study of place and health is Baguio’s local climate. Elevated at 5,000 feet above sea level, the city experiences temperatures ranging from 10C during the cold months of December, January and February to around 30C during the warm months of March, April and May. Cold temperatures often create an inversion effect that traps polluted air during the early mornings. Warm weather, on the other hand, often brings an onset of gastro-intestinal diseases because of food-borne bacteria found in non-refrigerated foods that vendors either sell or pack from home.

It is also known for its prolonged monsoon season in which rainy weather is evident from June to early September. During this season, a rise in the incidence of flu and other respiratory problems is common.

Vendor sites & urban architecture

The local spaces that hold vendors’ microbusinesses are varied, interesting and indicative of socio-economic factors. For example, the vendors who have established their territories for many years are located in spaces that are mostly flat and have high pedestrian traffic. Relative newcomers are left with secondary spaces in minor streets with moderate foot traffic.

|

Street vendor concentration nodes scattered throughout the central business district

|

Vendors select their spaces based on the type of products sold, friendships and ethnic affiliation. Fruit vendors tend to settle in places adjacent to eateries while those selling hard goods like t-shirts, DVDs and household products are found close to banks and retail outlets.

However, most, if not all, vendors use a part of the physical environment as a basis for their location decisions. The urban architecture found in central Baguio City is characterised by diverse building types, uses and forms. Four- to five-storied modern designed buildings frame the main street. Other buildings are modest, with only three stories with ordinary architecture.

Building architecture impacts on the quality of vendor sites. For example, only 25% of vendors are located under building overhangs that span the entire sidewalk.

In fact, about 32% of vendors are in sites that are not under any overhang. They are exposed to climactic elements like the monsoon rains and cold mountain air. Integral to urban architecture is the presence of sidewalks fronting the buildings.

As the owners have responsibility for constructing and maintaining sidewalks, the infrastructure is included in the overall design of the property. This results in varying heights, widths and quality of sidewalks throughout the central business district. Sidewalk widths vary from seven to 16 feet6. Sidewalk density, as measured by pedestrian counts and sidewalk widths, has an effect on health conditions. Higher sidewalk densities create environments that encourage the spread of communicable diseases like influenza, bronchitis and pneumonia, especially during the monsoon season.

Street vendors soften and personalise the existing architecture by creating work spaces made of simple materials to display their products and work ‘comfortably’ for ten hours a day. Cartons and cardboard boxes make up fruit stands and tarps are used to display special items. Other vendors use building walls as stands for posters and magazines. The colourful array of products contributes to the finer textures of urban places.

Air quality

In 2004 the research team monitored and assessed the air quality in 30 populated vendor sites and a fi xed site on the third floor of a building. Generally, the data showed elevated levels of pollution in many areas in the central business district. The data at the fixed site also indicated that particulate matter concentrations were higher than the National Ambient Air Quality Standards used in the United States.

Environmental factors such as building height, distance to a stoplight, street widths, number of street lanes and topography, as well as vehicular and pedestrian volume, were added to a group of other variables in a regression analysis model but were not found to be statistically significant. The factors that contributed significantly to street level pollution were traffic volume and wind direction7.

The built environment and health

In his treatise On Airs, Waters, and Places, Hippocrates strongly links disease with place, particularly, a community’s location and local climate8. This observation, though developed centuries ago, has come full circle as scientists today accept the connection between the physical environment and health. We have based this study of street vendors on Hippocrates’ findings but the discussion has been extended to include the impact of the built environment and air quality on health. The variables considered in the analyses were:

Physical environment factors: slope; vehicular volume; vehicular movement (idling, moving uphill); pedestrian volume.

Architecture and built environment indicators: building height; building overhang; curb height; distance to a drainage hole; distance to a garbage disposal; and quality of the sidewalk.

Air quality: morning and afternoon monitoring of: particulate matter 2.5; particulate matter 10; and carbon monoxide.

Health variables: number of health problems experienced in 2003; type of health problems.

Results

Using bivariate correlation tests, the results showed the following patterns:

Slope and health conditions: A correlation between slope and type of health condition was found to be significant (r=0.344, p<0.01, n=187). Interestingly, vendors who experienced infl uenza and fever were located in steep slopes.

However, when the data is examined more closely, these locations were also vendor sites with shorter sidewalk widths and higher sidewalk densities. The close proximity of vendors and pedestrians may contribute to the incidence of communicable diseases.

Vehicular movement: Vendors located in streets that have fast moving vehicles tend to have higher number of health episodes (r=0.155, p<0.05, n=187). However, it seems that another factor is involved in this situation.

|

|

Before and after: An important part of the environmental design plan is to 'pedestrianise' several streets in the central business district

|

When correlation tests were conducted on measures of air quality and vehicular movement, we found that streets with fast moving vehicles in the early morning hours have the highest levels of pollutants (i.e. PM2.5, PM10, CO). The effect of nocturnal inversion is evident here. Considering that vendors arrive at their locations as early as 5.00am, they are exposed to high pollution levels at the start of their work day.

A thorough case study approach used to determine the relationship between vendor sites and health conditions was also conducted for the various sites. Of the 31 sites examined, two sites were the most problematic in terms of pollution levels and reported health problems.

The first site was Magsaysay Avenue, a highly congested artery leading traffic from the eastern portion of the city to the downtown area. It is also here where the public market and three adjacent universities are located. The vendors on that street reported incidence of colds, asthma, high blood pressure and arthritis.

Magsaysay Avenue has narrow sidewalks, compared to the other streets. The influx of students and people heading to the city market contribute to Magsaysay Avenue’s pedestrian counts, which is the highest among all other streets in the central business district (40 persons per minute).

As indicated earlier, communicable diseases such as influenza and colds are easily spread in dense environments.

Although the buildings’ overhangs along Magsaysay Avenue cover about 100% of the sidewalks, protecting vendors from the monsoon rains, they also create a tunnel effect. With concrete walls and sidewalks this workplace can be very cold in the morning.

This threatens vendors’ immune systems, making them vulnerable to colds, coughs and even arthritis. The results of the air quality monitoring phase of the research study also shows that Magsaysay Avenue site is one of the most polluted places in the CBD, especially during the afternoon rush hour. High traffic volume, idling vehicles that run on diesel fuel and disrupted circulation flow, as public vehicles drop off their passengers in undesignated spots, are responsible for the poor air quality in this street. Vendors suffer from asthma, intense headaches and high blood pressure.

Another site that gives evidence to the relationship between the built environment and health is Assumption Road, a secondary street that intersects the main street. The results of the 2003 health survey show that vendors here were sick three times more than the other vendors throughout the central business district. Among the health problems they experienced were colds, tightness in the chest, trouble breathing and intense headaches. The air quality is extremely poor during the morning rush hour.

Vendors are located along a steep one-way street leading to several elementary schools and the heavy morning traffic consists of diesel fuel vehicles idling on an incline. Such a substandard environment may be causing some of vendors’ health problems.

Compared to Magsaysay Avenue and Assumption Road, Harrison Road is considered the ‘healthiest’ site of all. Unlike other sites with similar traffic volumes, this street has the best air quality conditions. A major explanation for such good air quality is that the two sites on Harrison Street are adjacent to the main public park in Baguio City. Burnham Park is about an acre of green that stretches along Harrison Street. Its trees and good wind circulation mitigate the impact of vehicle exhaust on vendors’ health conditions. Those located on this street did not report as many ailments as the others.

Design and planning implications

These results clearly demonstrate the relationship between health and the built environment. In the case of Baguio City, a drastic transportation plan to decrease the volume of traffi c in the central business district will improve the health of not only street vendors but also the general population that live, work, recreate and go to school in the area.

Table 1: Research protocol for the street vendor study

|

| Year |

Research focus |

Research methodology |

| 1999 |

Social networks; microeconomic nature of street enterprises; built environment assessment |

Survey of 219 vendors; physical inventory of vendor sites |

| 2000 |

Relationships between street vendors and adjacent formal businesses |

Visual documentation and informal interviews |

| 2003 |

Health and environmental assessment |

Survey of 187 vendors; physical inventory of vendor sites |

| 2004 |

Air quality |

Air quality monitoring on 30 vendor sites and one central fixed site |

| 2006 |

Health screening and visual documentation |

Medical screening for 15 vendors (eg, physicals, blood tests, oximeter readings at vendor sites); in depth health survey for 10 vendors; visual documentation of 30 vendor sites |

A conventional solution would be to construct a bypass around the urban core – but that approach is far from being sustainable. To preserve the character of the city’s centre, highways should not be built because these structures will only increase the dark and cold tunnel effect of urban spaces beneath them.

Rather, a framework that encourages satellite service centres around the city will decrease the number of vehicles entering the urban core. Banks, professional offices, medical offices and other businesses can relocate to disperse services around the city.

An important part of the environmental design plan is to ‘pedestrianise’ several streets in the CBD. This move will decongest the sidewalks and encourage the use of urban spaces for more community-oriented (social, leisure, cultural, and arts) activities and active living, while increasing their economic vitality.

Several cities in India and Indonesia have closed major streets to accommodate pedestrians9. Evaluations of these planning strategies have yielded positive results. Businesses have increased their sales, air quality improves, users are more encouraged to stay in these places, crime decreases and urban spaces are enlivened.

Lastly, to improve the health of street vendors and urban residents living, working or visiting in the CBD, a greening movement should be embarked upon. Restoring existing parks to better health and planting vegetation around the CBD will improve air quality and decrease the effects of the urban heat during the hot, summer months.

Next steps

This longitudinal study of street vendors is an example of a transdisciplinary work. The extensive quantitative and qualitative data that was collected provided a description of places and people which helped us understand the relationship between the built environment, architecture and the health of, in this case, street vendors in the Philippines.

However, to validate the implications of the study results, a tangible intervention, such as implementing a transportation scheme to decrease traffic in the central business district, is necessary. Medical screening tests, pre- and post-intervention, can be extended to include the entire sample of vendors. These next steps would indeed put closure to the entire project.

Authors

Mary Anne Alabanza Akers, PhD, Dean, School of Architecture and Planning, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland, US

Timothy A Akers, PhD, assistant dean for research, School of Community Health and Public Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland, US

References

1. United Nations. Human settlement country profile. Washington DC: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Sustainable Development; 2004. Retrieved August 31, 2007 from www.un.org/esa/agenda2/natlinfo/countr/philipi/humansettlements2004.pdf

2. Furman A and Mehmet L. Semi-occupational exposure to lead: a case study of child and adolescent street vendors in Istanbul. Environmental Research 2002; 83(1): 41-45.

3. Pick WM, Ross MH and Dada Y. The reproductive and occupational health of women street vendors in Johannesburg, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine 2001; 54(2): 193-204.

4. Ruchirawat M, Navasumrit P, Settachan D, Tuntaviroon J, Buthbumrung N, Sharma S.. Measurement of genotoxic air pollutant exposures in street vendors and school children in and near Bangkok. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2005; 206(2):207-214.

5. Akers MAA, Sowell R and Akers TA. A conceptual model for planning and designing healthy urban landscapes in the Third World: a study of street vendors in the Philippines. Landscape Review 2004; 9(1):45–9.

6. Akers MAA, Akers TA. Urbanization, land use and health in Baguio City, Philippines. In G. Guest (Ed.), Globalization, health, and the environment: An integrated perspective. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press; 2005.

7. Cassidy BE, Akers MAA, Akers TA, Hall DB, Ryan PB, Bayer CW, Naeher LP. Particulate matter and carbon monoxide multiple regression models using environmental characteristics in a high diesel-use area of Baguio City, Philippines. Science of the Total Environment 2007; 381 (1-3): 47-58.

8. Hippocrates. On airs, waters, and places. 400 BCE. (F. Adams, Trans.) Retrieved September 30, 2006 from http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/airwatpl.1.1.html

9. Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. Pedestrianizing Asian cities. Sustainable Transport 2003; 22-25. Retrieved November 10, 2006 from www.itdp.org/documents/st_magazine/ITDP-st_magazine-15.pdf

|

1.1.jpg)

|