Design characteristics of healthcare environments: the nurses’ perspective

This study aims to identify the most important characteristics of a work environment that fully support nurse health and performance, as expressed by nursing staff

Rana Sagha Zadeh, Mardelle McCuskey Shepley, Laurie Waggener, and Laura Kennedy

By its very nature, nursing is a stressful profession. To succeed in the field, nurses must possess the technical skill to solve complex problems, the emotional strength to deal with sick patients, and the stamina to endure long, arduous shifts.1 Demand for nursing professionals has increased steadily in recent years owing to the following factors: ageing populations,2 rising life expectancy3 and increasingly complex medical issues globally.4 Meanwhile, the difficulties associated with recruiting and retaining nurses have exacerbated.5 With nursing positions accounting for up to 75% of vacant jobs in the hospital workplace,6 the shortage is already a prominent issue and is expected to almost double by 2020.4

Both physically and mentally demanding, nursing is a profession for those who possess a unique and selfless passion to care for others.7,8 Yet, the challenging quality of the work has resulted in high job-dissatisfaction rates,7,8,9 high turnover rates10 and increased stress.11 Nursing ranks as one of the top-10 least satisfying professions in the United States.8 Because of its reputation, nursing has become less attractive to younger generations;5 consequently the nursing population is ageing rapidly.2 Older nurses become less physically able to perform tasks with age,2 and employed nurses further feel the burden of the nursing shortage by taking on longer work hours and more patients.1

The current shortage is thus a combination of three related issues – declining enrollments in nursing schools,13,14 reduced motivation to stay in the field, and the high number of nurses retiring and leaving the profession prematurely – which must be addressed separately.14 The most common tactic used to solve nursing shortages is to invest in increasing recruitment of younger generations.15,16 But these fall short in solving the current complex nursing shortage.17,18,19 A practical solution is to focus on improving nurses’ working conditions, especially the nursing work environment, which, according to Peterson,20 is the most influential factor for recruitment and retention.

As healthcare operations and services grow ever more complex, all of the aforementioned conditions – the increasing demand for nursing professionals, the current shortage in the nursing workforce, the ageing of the workforce, and deteriorating job-satisfaction ratings – have immense implications for the future of healthcare design. Creating a supportive, high-performing work environment could not only increase recruitment and retention but also enhance the job satisfaction and efficiency of those already working in the field.21 In short, if nurses are less exhausted, both physically and mentally, they provide better and safer care for their patients.

In this study we make use of those closest to the issue of the workplace environment to best understand potential solutions. Nurses should have the most influence on healthcare workspace design because they can identify a large number of issues from personal experience.22 Recording and analysing nurse feedback on their existing work environments can help prioritise strategies for change and uncover innovative design solutions that stem from user experience. This report identifies the most important strategic design solutions to create a high-performance work environment for nurses, with the goal of improving nurse health, productivity and work satisfaction.

|

|

| Figure 1: A ‘boxed-off’ design and some types of artificial lighting can create an institutional feel |

Figure 2: Connections to the outdoors help with orientation. Apply light fixtures and finishes that minimise glare and create a non-institutional feel |

Methods

This study was conducted in two healthcare facilities in the United States: one outpatient clinic with 20 exam rooms providing primary and preventative care, and one 80-bed inpatient unit within a hospital providing comprehensive care. Full-time registered nurses (RNs) in inpatient and outpatient settings were eligible participants for this study. Participants included both female and male nurses working either the day shift or the night shift.

Anonymous-survey forms and information sheets were distributed to the RNs during monthly staff meetings in both facilities, and made available in staff work areas for those who were unable to attend the meetings. A number of survey drop boxes were provided at each facility for RNs to return their responses.

Participants supplied responses to the unstructured survey, describing the characteristics of a work environment that would support their health and performance. The feedback was compiled by content into various categories, and those containing the most frequently discussed topics were identified. The aforementioned method of ethnographic data analysis is called content analysis,23 and it was used in this study to identify objectively the most important characteristics of nursing workspaces.

|

| Figure 3: There is a need for more personal space. Lack of sufficient space affects posture and comfort, resulting in unnecessary fatigue |

Results

|

Figure 4: Hospitals should anticipate storage needs and provide easily accessible storage space, including space for computers on wheels, soiled baskets, isolation storage carts and advanced-cardiac life-support carts

|

Of the RNs who were eligible for this study, 71% participated (n=80): 86% (n=69) female, and 14% (n=11) male. Fifty-three (n=53) respondents (66%) at the inpatient facility worked the day shift, while 34% (n=27) worked the night shift.

According to content analysis of nurse responses from both day and night shifts, the most important characteristic of a healthy and productive workplace is “adequate workspace”. The summary of nurses’ descriptions indicates that a lack of adequate space has negative consequences for productivity, physical health and social wellbeing. Half of the surveys included at least one comment emphasising the need for appropriately sized workspace.

Several factors were noted as being particularly important to creating a productive workspace: adequate desktop surface space, specifically for charting; sufficient room to move around; avoidance of clutter; and ample space to accommodate all staff (including RNs, ancillary staff and physicians) concurrently, especially during shift changes, or when reports or rounds are carried out. Insufficient space was associated with incidents resulting in added stress, inefficiency and reduced personal privacy. Moreover, interpersonal conflicts among RNs, or between RNs and physicians, have resulted from lack of space. One nurse stated that the ideal workspace would have sufficient room “for which I do not have to fight”! Ergonomic issues can also arise when physical space is limited, because staff cannot stretch their legs or work comfortably with the computers. Two nurses pointed out this issue, specifically asking for “room to stretch limbs” and “elbow room”.

The second most frequently mentioned environmental condition was lighting. The RNs emphasised the necessity for well-lit spaces and absence of glare. Most RNs also described the need to have natural lighting, sunlight and windows at workstations. Desired qualities described by a number of RNs were adjustability, uniformity and less institutional fluorescent lighting (Figures 1 and 2).

The next most frequently-mentioned need among nurses was ergonomically designed and comfortable furniture. Adjustable desk-height, comfortable and supportive chairs, well-designed keyboards and desks, and a large computer screen with appropriate line of sight were specifically emphasised by the RNs in this study (Figure 3). A healthy and productive workspace design should not require frequent bending or stretching to access basic equipment and supplies, or to complete tasks.

The fourth most important element in healthy and productive workspace, according to the RNs, is sufficient and suitably located equipment and supplies, such as power outlets, which satisfy required environmental considerations. Easy access to sufficient equipment and supplies with ample storage, reachable and sufficient electric outlets, computers, phones, fax machines, call bells and office supplies help improve productivity.

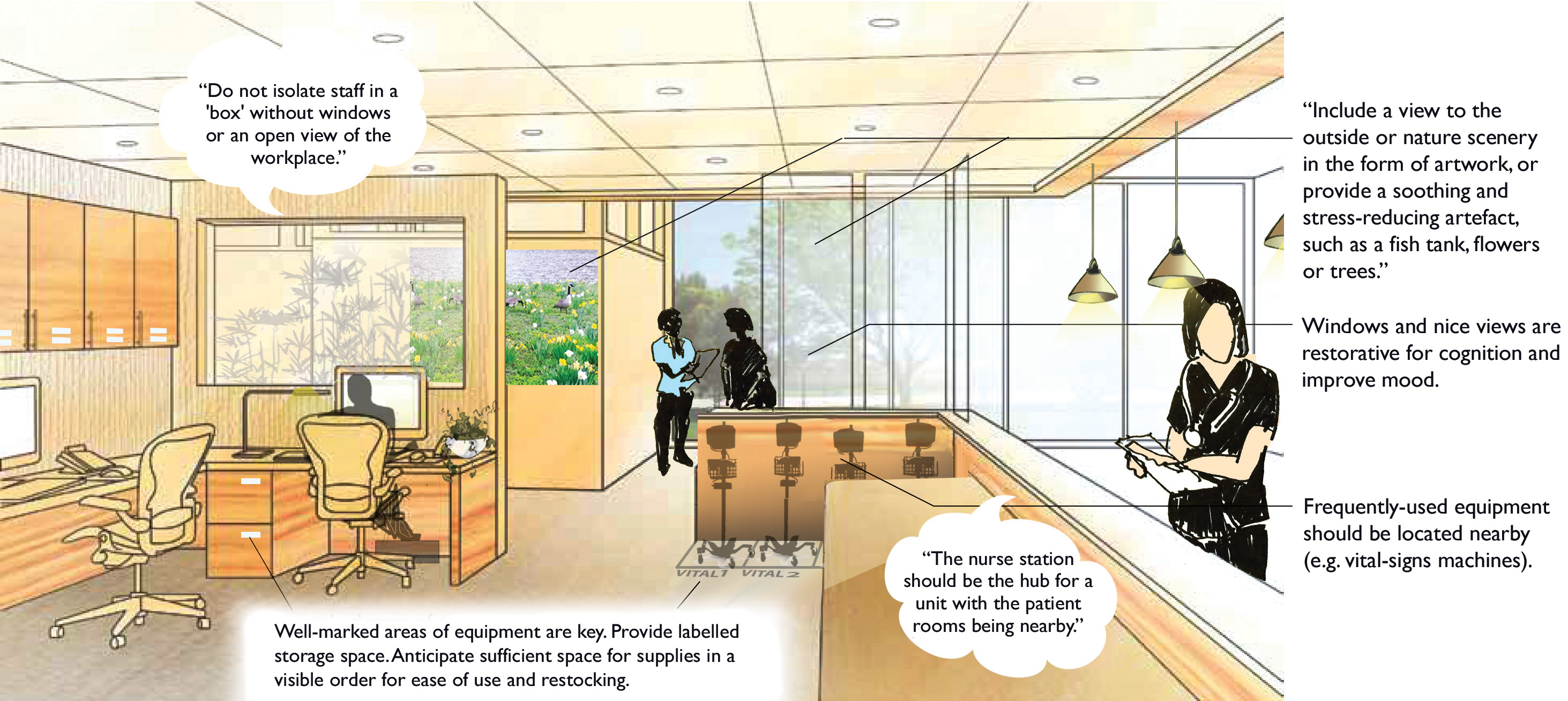

Design that helps maximise work organisation and supports preparedness is the fifth most important characteristic of a well-planned nursing workspace. Preparedness in the workplace design enables staff to act quickly in case of emergency. Sufficient room that allows easy organisation and visual and physical access to supplies and equipment improves efficiency and reduces time spent hunting and gathering. Consistent organisational features among nurse stations, medication rooms, and supply areas are important for time efficiency and boosting productivity. Designated spaces for staff and well-marked equipment areas are key (Figure 4). Design elements that enable staff to identify quickly or mark non-functional equipment, and spot missing or non-stocked supplies could lead to considerable improvement in productivity. Furthermore, designated workspaces for RNs, physicians and social workers – and those who undertake rounds, such as physicians and physical therapists – will enhance work organisation and reduce disturbances when staff leave their stations.

Other important characteristics described in the surveys include efficient layout, convenient physical access and visual access, privacy and security, minimal noise, and the availability of windows and nature views.

The findings of this study indicate that general architectural features – including allocated floor space, layout, circulation, visibility, access to the outdoors and natural light – form the foundation for creating a high-performance, healthy workspace. But detailed interior design features, such as furniture, finishes, fixtures and equipment, are critical in transforming a facility into a high-performance workspace for health and productivity.

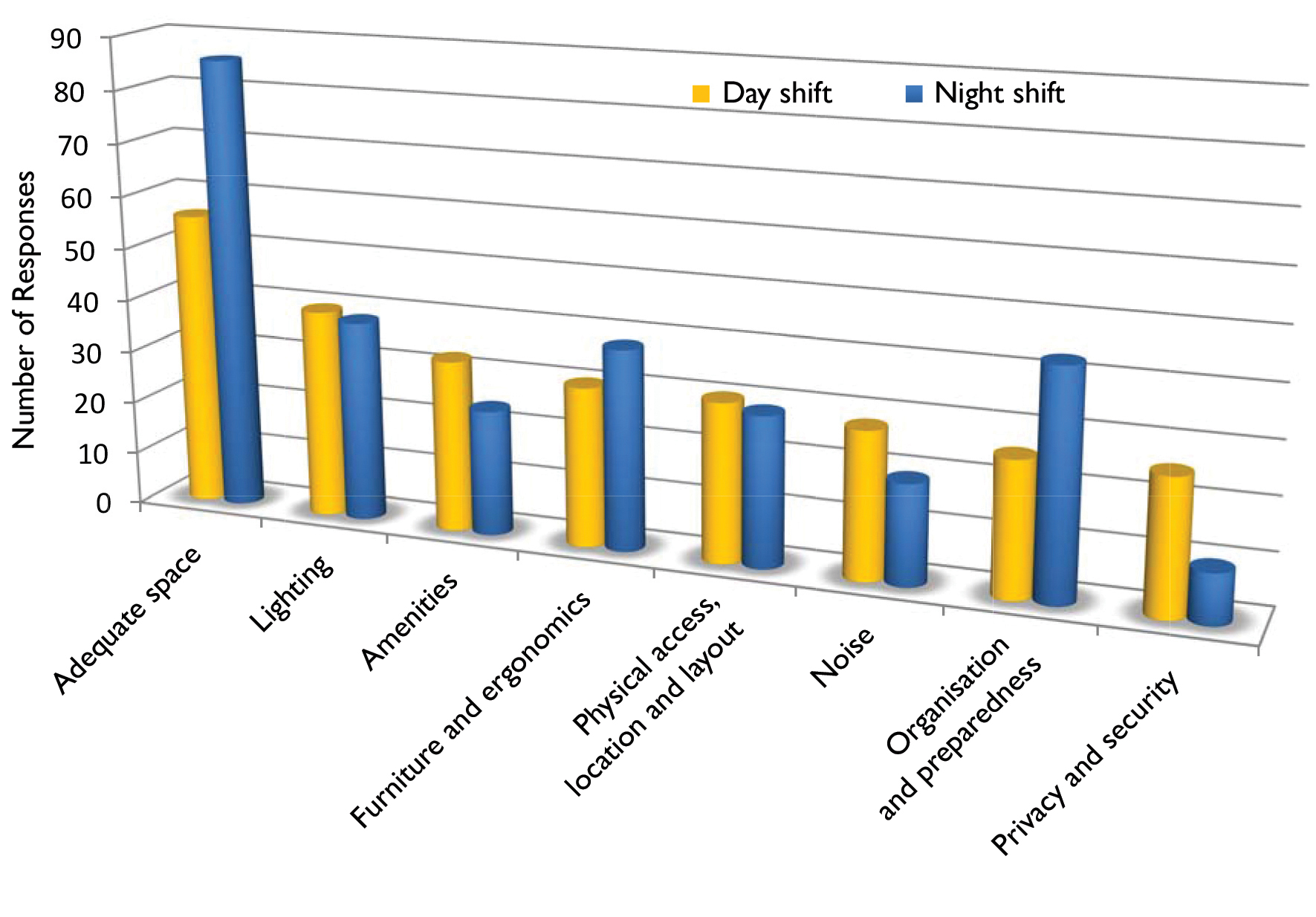

When analysing the subgroups of day shift and night shift, variations emerge in which healthy workplace characteristics were most emphasised. Night-shift nurses discussed more frequently the need for adequate space at individual workstations and good ergonomics, adequate space for stretching, “elbow room” and charting space (Figure 5). The next most popular characteristics for night-shift staff were comfortable, height-adjustable furniture and seating. Lighting was equally important for night-shift and day-shift workers, but ample bright light and high-quality lighting is particularly critical during night shifts (Figure 6). Environmental design considerations to maximise work organisation and preparedness were highlighted more by night-shift workers, especially with regard to storage and stocking. However, noise at the nursing workstations posed less of an issue to work during the night shift than during the day shift. These results indicate the value of designing for flexibility to allow staff to adjust their workstations according to their needs.

Design suggestions

The key characteristics of the work environment that promote productivity and health, according to the surveyed RNs, are listed below in order of importance.

|

Figure 5: The most important design characteristics of nursing workstations vary between day-shift

and night-shift RNs

|

1. Adequate workspace

- Provide adequate circulation spaces and workstations to ensure that nurses are not interrupted when undertaking charting work, and to prevent clutter.

- Consider that, at times, doctors, ancillary staff and RNs gather simultaneously around the nurse station. Anticipate how the space accommodates staff during shift-change reports, when the number of staff doubles while critical patient information is communicated to those on the next shift. Additional foldable or appropriately sized furniture can be stored. Lack of space disturbs privacy and can undermine the atmosphere of teamwork, and cause conflict.

2. Appropriate lighting

- Provide bright, glare-free and soft light and design to allow for as much natural daylighting as possible. One nurse stated: “Natural lighting keeps [me] from getting depressed”; another commented: “I would like to be able to see well when working on patient charts and retrieving medication.”

- Fluorescent lighting or finishes, which give a sense of institutional atmosphere, should be avoided. Apply finish surfaces that “look good, fresh and clean”. Remember that nurses work long hours, so use warm colours and peaceful themes. Nurses report that they “get eye strain when all their surroundings are … stark white”.

3. Furniture and ergonomics

- Provide workplaces that are designed ergonomically to maintain the health and performance of staff. Easy-to-reach supplies without the need to bend or stretch constantly, and chairs and tables that are adjustable and comfortable, reduce fatigue and improve health.

4. Amenities

- Anticipate adequate supplies and equipment, such as phones, computers, printers, fax machines, etc. Provide ample reachable power outlets. Provide easy access to bathrooms and refreshments.

- Consider access to music or radio for individuals, as RNs noted that music “could help the day pass”.

- Frequently accessed resources, such as linens, medication, nourishment, supplies and refreshments, should be nearby, within “quick access to the hub”.

5. Organisation and preparedness

- Design “consistent features and organisation at each desk/work area”. Designate spaces for staff and allocate areas for organising equipment, materials, and supplies. Anticipate designated spaces for RNs, doctors, social workers and other staff. Label storage spaces for supplies and ensure they are easy to reach and visible. One nurse requested “supplies in a visible order for ease of use and restocking”. Anticipating design features that help signal missing supplies for restocking or broken equipment is an effective way to reduce wasted time. Informed by unit staff, designers should designate areas for that which is most important (eg vital-signs machines) in the nurse station, or within a few feet.

6. Physical access, location and layout

- Layout is key to work performance. Locate the most frequently accessed supplies around the nurse station “with the least amount of walking to patient nourishment, linens and medication”. The ideal layout, as visualised by RNs, is one where the “nurse station is the hub for a unit, with the patient rooms being not too far from it”.

7. Noise

- Noise must be suitably controlled, so consider movable and fold-down screens that can be deployed as needed. Nursing staff often “have difficulty concentrating when [it is] noisy” and are “frequently distracted”, but the use of acoustic surfaces and physical barriers, such as glass, to control noise should ensure that nurses can concentrate during their work.

8. Privacy and security

- The outside windows opening into nurses’ stations should “be semi-secluded from public eye” to respect patient-information privacy.

- One nurse suggested that the hub should be “surrounded by glass windows above the countertop, with easy access points; this will reduce noise and help keep the patient records private”.

9. Windows

- Include windows in nurses’ workstations. Nurses stated their desire for a “view to [the] outside or nature,” “pleasant scenery” in the form of artwork, or a soothing and stress-reducing artefact “like a fish tank, flowers or trees”. Such features are restorative for cognition and help with mental balance during work. A well-designed workspace does not “isolate staff in a box without windows, [or without an] open view of [the] workplace”.

- Nursing areas should have good ventilation and ambient temperature. As one nurse expressed, staff need “clean air to breathe”.

10. Visual access

- Visibility to the surroundings is critical. Consider patient visibility for every location, specifically those areas where nurses frequently work. “Enable nursing staff to see the patients, with the least amount of walking” and provide views of the hallways and rooms.

|

Figure 6: Lighting; physical access; location, layout and noise

|

|

Figure 7: Adequate space; furniture and ergonomics; and amenities

|

|

Figure 8: Organisation and preparedness; and windows

|

|

Figure 9: Privacy and security, and visual access |

Conclusion

Design of nursing-work environments can facilitate or hinder care. Good facility design is a strategic investment that can support staff health and boost their productivity. The primary needs of staff, as suggested by this study, are adequate space, lighting, furniture and ergonomics, amenities, and organisation and preparedness.

This study was conducted in the United States, so further research in more facilities and in a variety of geographical regions would help provide a broader picture of suitable design solutions for nurses’ work environments. The study was also limited in respect that only feedback from RNs was recorded, so additional research is needed to capture the key characteristics of the work environment for other medical staff, including physicians.

Authors

Rana Sagha Zadeh MArch PhD Associate AIA EDAC is assistant professor in design and environmental analysis at Cornell University. Mardelle McCuskey Shepley DArch FAIA FACHA EDAC LEED AP is Skaggs-Sprague endowed chair in health-facilities design and director of the Center for Health Systems & Design at Texas A&M University. Laurie Waggener RRT IIDA AAHID EDAC is research and evidence-based design leader at WHR Architects, Inc. Laura Kennedy BS EDAC works in the design and environmental analysis team at Cornell University.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Gary Williams, MSN, RN and Martha Dannenbaum, MD, and all healthcare personnel for their key support and guidance, Marie McKenna for her help with image renderings, Susan Sung Eun Chung for data analysis and management, and Center for Health Design for its financial support via the New Investigator Award.

References

1. Phillips, S. Labouring the Emotions: Expanding the Remit of Nursing Work? Journal of Advanced Nursing; 1996, 24:139–143.

2. Buerhaus, P, Staiger, D, and Auerbach, D. Implications of an Ageing Registered Nurse Workforce. Journal of American Medical Association; 2000, 283(22):2948-2954.

3. Oeppen, J, and Vaupel, J. Broken Limits to Life Expectancy. Science; 2002, 296:1029-1031.

4. Bowles, C, and Candela, L. First Job Experiences of Recent RN Graduates: Improving the Work Environment. Journal of Nursing Administration; 2005, 35(3):130-137.

5. Kramer, M, and Schmalenburg, C. Job Satisfaction and Retention. Nursing; 1991:50-55.

6. Choi, J, Bakken, S, Larson, E, Du, Y, and Stone, P. Perceived Nursing Work Environment of Critical-Care Nurses, Nursing Research; 2004, 53(6):370-378.

7. Huey, F, and Hartley, S. What Keeps Nurses in Nursing. American Journal of Nursing; 1988, 88(2):181-188.

8. Johnson, S, Cooper, C, Cartwright, S, Donald, I, Taylor, P, and Millet, C. The experience of work-related stress across occupations, Journal of Managerial Psychology; 2005, 20(2):178-187.

9. Aiken, L et al. Nurses’ Reports on Hospital Care in Five Countries. Health Aff (Millwood); 2001, 20(3):43-53.

10. Hayes, L et al. Nurse Turnover: A Literature Review. International Journal of Nursing Studies; 2005, 43:237-263.

11. McVicar, A. Workplace Stress in Nursing: a Literature Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing; 2003, 44(6):633-642.

12. Aiken, L, Clarke, S, Sloane, D, Sochalski, J, and Silber, J. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. Journal of American Medical Association; 2002, 288(16):1987-1993.

13. Sochalski, J. Nursing Shortage Redux: Turning the Corner on an Enduring Problem. Health Affairs; 2002, 21(5):157-164.

14. Berliner, H, and Ginzberg, E. Why This Hospital Nursing Shortage is Different. Journal of American Medical Association; 2002, 288(21):2742-2744.

15. Hayhurst, A, Saylor, C, and Stuenkel, D. Work and Environmental Factors and Retention of Nurses. Journal of Nursing Care Quality; 2005, 20(3):283-288.

16. Janiszewski, H. The Nursing Shortage in the United States: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing; 2003, 43(4):335-343.

17. Lamm, E. Examining Nursing School Strategies for Recruitment and Retention of Nursing Faculty: An Exploratory Study. Proquest; 2011.

18. Oulton, J. The Global Nursing Shortage: An Overview of the Issues and Actions. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice; 2006, 7:34S-39S.

19. Kimball, B, and O’Neil, E. Healthcare’s Human Crisis: The American Nursing Shortage. Health Workforce Solutions; 2002, 1-77.

20. Peterson, C. Nursing Shortage: Not a Simple Problem. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing; 2001, 6(1).

21. Kramer, M, and Schmalenberg, C. Confirmation of a Healthy Work Environment. Critical-Care Nurse; 2008, 28:56-63.

22. Ulrich, B, Norman, L, Buerhaus, P, Dittus, R, and Donelan, K. How RNs View the Work Environment. Journal of Nursing Administration; 2005, 35(9):389-396.

23. Lincoln, Y, and Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985.

|

1.1.jpg)

|