Design Quality Standards: Intangibles that bring hospitals to life

This research project assesses the effectiveness of a step-by-step model for developing site-specific, meaningful and measurable design quality standards, while creating supporters who were prepared to implement them.

Tye Farrow, BArch, MArch UD, OAA, MAIBC, NSAA, NAA, FRAIC; Sharon VanderKaay, BSc Design, ASID

|

Bluewater Health in Sarnia, designed to provide ‘light, life and comfort’

(photo courtesy Farrow Partnership) |

For over 25 years, the terms ‘patient focused care’ and ‘healing environment’ have been in common use by hospital administrators and healthcare design professionals. Despite well-intentioned efforts to provide psychosocially supportive settings, we continue to see spaces that demonstrate little empathy for the vulnerable state of patients, family and staff1.

Canadian architecture critic Lisa Rochon has described the majority of hospital environments as “factories built to contain the ill”. She continues: “Sadly, for the most part, inspired hospital design is wishful thinking.”2

|

|

Figure 1: The Hospital Asset-Liability Pyramid illustrates how intangibles can contribute to wealth creation

|

While there are rigorous technical construction codes that dictate the requirements for fire and life safety, no code protects the public from exposure to austere healthcare infrastructure. To avoid the risk of building hospitals that function merely to process sick people, decision-makers must confront the inherent challenges of defining, monitoring and implementing intangibles.

For example, the intangible design qualities of a hospital influence its position on the Asset-Liability Pyramid (Figure 1). In contrast to technical standards, design standards cannot be validated by means of traditional scientific methodologies. However, if such barriers to working with intangibles are viewed as insurmountable, it will be difficult to make a convincing case in support of economically vibrant healthcare assets.

Generic and vague statements such as ‘patient-centred’ or ‘re-thinking the 21st-century hospital’ may represent the sincere aspirations of decision-makers; however, these phrases are inadequate when creating meaningful, location-specific design quality standards.

Desire v reality

The research presented in this paper set out to examine the nature of gaps that frequently occur between espoused desires to create a ‘healing environment’ and the built reality of these spaces. This research began broadly by reflecting on over 10 years of conscious experimentation in the field with client stakeholder groups. Six questions were raised at this early stage:

1. Why is there frequently a gap between espoused aspirations and physical reality?

2. Can one assume that improved design quality standards will inevitably result in truly therapeutic hospital environments?

3. Are decision-makers capable of discerning the difference between facilities that are merely new in contrast to facilities that address complex psychosocial issues?

4. What motivates administrators and politicians to take a strong advocacy role in achieving optimal human-centric design?

5. What motivates apathetic or hostile decision-makers to become strong advocates for improved design standards?

6. Can we assume that the causal connections between intangibles – for example, design that conveys a meaningful identity and makes an emotional connection – and tangible outcomes, such as attracting staff and major donors, are apparent to decision-makers?

Several preliminary hypotheses for further study were identified as possible responses to questions 1-6 above. All of the themes that emerged from this early stage of inquiry were related to an inconsistency between espoused values and built reality. Explanations for this discrepancy that appeared worthy of further investigation included:

- a lack of rigour in defining what constitutes a therapeutic healthcare environment;

- believing that intangibles are too abstract to meaningfully define and monitor;

- failure to assist decision-makers in connecting intangibles to tangible outcomes;

- expecting stakeholders to appreciate and support imposed standards; and

- underestimating the hidden potential of even the most vocal naysayers to become enthusiastic advocates for quality design standards.

|

Peel Regional Cancer Centre radiation maze (photo courtesy Farrow Partnership)

|

In order to address all of the above issues, Farrow Partnership Architects has developed a highly participatory, step-by-step consulting model. This model, described below, draws on Farrow’s collective knowledge of adult learning principles and intangible value creation.

The intangible nature of human-centric design quality criteria is a factor that can deter decision-makers from committing resources toward improving these standards. However, in order to progress beyond current hospital design norms, new approaches are needed for creating effective standards, as well as for attracting influential advocates.

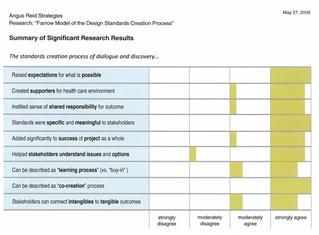

The model was evaluated by Angus Reid Strategies in its research report, Evaluating the Farrow Model of the Design Standards Creation Process, dated 27 May 2009. For this study, Angus Reid collected qualitative survey data from six community hospital client representatives using a combination of closed and open-ended questions3.

Background

The specific design quality standards procedures and tools evaluated by this qualitative research project were developed over a 10-year period through a process of discovery, inquiry and reflection. In addition to field observation and experimentation, the procedure and tools were informed by literature research regarding 1) the nature of intangibles4 and 2) adult learning principles5.

Listed below are qualities and characteristics that have been identified by experts4, 5 as inherent to intangibles, and on which the design quality standards process and tools in this study are based.

1. Intangibles are a pre-condition for tangible benefits.

2. The connection between intangibles and tangibles is not always obvious.

3. Intangibles are typically valued at zero by accountants who avoid assigning rough numbers.

4. Intangibles are susceptible to being dismissed by decision-makers who believe only what can be counted counts.

5. A first-hand hospital stay can suddenly change the mind of decision makers who believe that only what can be counted counts.

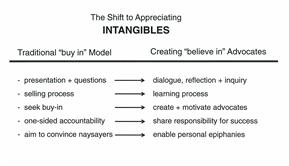

The design quality standards model, as defined in this study, draws on adult learning theory. In the 10-year development of this methodology it was hypothesised that stakeholders require a learning process to effectively implement effective standards, rather than a selling (commonly referred to as a ‘buy-in’) process. Listed below are the adult learning principles6 applied to the quality standards creation and implementation process that is the subject of this study.

1. Adults learn best when they perceive a gap between what they know and what they need to know (i.e. imposed, highly ambitious standards may be rejected out of hand) or gaps between what is and what can be

– for example, “Let’s examine a range of socalled ‘healing environments’ to learn what is possible and the extent of any gaps.”

2. Adults learn best when they engage in a dialogue and inquiry process rather than through a lecture or one-way presentation – i.e. a process based on shared inquiry and discovery rather than the traditional buy-in model.

3. Adults learn best when the subject makes an emotional connection – predetermined quality standards, however rigorous, may be regarded by stakeholders with indifference unless these standards gain personal significance.

4. Adults learn best when they are provided the context to make their own cause-and-effect connections. Some links between intangibles and value creation are not always obvious; these links can be identified through dialogue between stakeholders and designers.

5. Adults learn best when they have opportunities for personal revelations, also known as the ‘a-ha moment’ or a personal epiphany.

Method

For this research project, Angus Reid Strategies conducted semi-structured interviews consisting of approximately 30 standard questions with six key client representatives who had participated in a variation of the standards creation model described below.

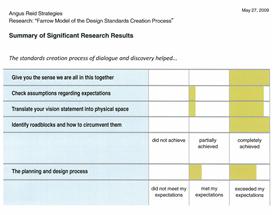

Participants were asked to assess the effectiveness of this process in designing a human-centric healthcare environment using a four-level Likert scale. Respondents were encouraged to make comments above and beyond the survey questions while being assured that all of their responses would remain anonymous. The survey aimed to test the process against four objectives:

- to help check assumptions regarding what people expect;

- to help identify potential roadblocks and how they might be circumvented;

- to translate your vision and values statements in to actual physical space; and

- to give a sense that this is something “we are all in together”.

The standards process and tools creation model that was the subject of this qualitative assessment consisted of the following steps.

Prepare stakeholders

Prepare stakeholders to participate in a facilitated dialogue session (which came to be known approximately four years ago as ‘Common Ground’) that has defined boundaries and outcomes, rather than a traditional meeting governed by an agenda, or a presentation and questions format.

In contrast to being issued a rigid agenda prior to the session, invitees received a ‘Purpose, Principles and Expectations’ document that briefly described the dialogue process, listed sample questions they could think about ahead of time and defined anticipated outcomes for the session.

|

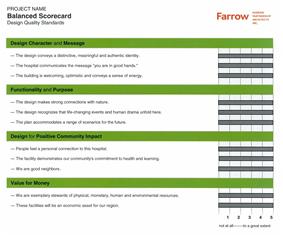

| Figure 2: The Balanced Scorecard helps measure the gap between meaningful criteria and what is being proposed |

Engage in dialogue sessions

Engage stakeholders in learning process-based facilitated dialogue sessions. These sessions were eventually branded as ‘Common Ground’, ‘Critical Eye’, and ‘Scenarios for the Future’ in order to set them apart as a reliable, repeatable set of workshops with defined tangible and intangible outcomes. The gap assessment tool that emerged from these sessions was known as the ‘Facilities Balanced Scorecard’.

Reflect on roles

Ask stakeholders to reflect on their role as representing countless other citizens in the community for, potentially, generations into the future. This step helps participants think beyond their official title to their role as a communicator who assists others in learning about project priorities and challenges on an everyday basis. As well, this step highlights participants’ legacy and their shared responsibility for a successful project, rather than soliciting buy-in to prepackaged quality standards.

Analyse local aspirational phrases

Jointly analyse locally-used aspirational phrases such as ‘patient focused care”, including selected terms from the organisation’s vision and values statements, for example, ‘healthy communities’. During the dialogue sessions, examine what these terms mean to the specific stakeholders in the workshop. For example, must ‘patient focused care’ overshadow ‘staff focused care’? Can a health- and human focused environment fulfill the needs of all?

|

Figure 3: A new model for working with intangibles When seeking support based on tangible criteria, such as hard numbers, the traditional model may still be effective; however 10+ years of experiments in the field indicate that human-centric design quality standards require a different approach

|

This step recognises that stakeholders typically have limited experience in evaluating intangibles such as ‘instilling confidence’ and ‘conveying a strong identity’. The dialogue process gives participants an opportunity to become constructively critical of vague design objectives (See Figure 3).

While some design quality standards can be applied universally, such as “Our hospital conveys the message ‘you are in good hands’”, there are individual historically and culturally meaningful priorities that contribute to creating positive emotional connections. A generic ‘anywhere’ hospital may be sufficient for functioning at the bottom of the Hospital Asset-Liability Pyramid shown in Figure 1; however, a sense of individual identity is a key component of the value creation model.

Examine tangibles and intangibles

Jointly examine the connection between tangibles and intangibles. Through the dialogue process, make the hidden (or less obvious) links between design and design outcomes more recognisable. This step helps apathetic decision-makers or naysayers see that design standards (based on intangibles) are a necessary pre-condition for tangible benefits such as attracting donors or reducing length of stay for patients.

Ask in-depth questions

Ask in-depth philosophical questions that highlight the value of intangibles and design quality standards, as well as the cost of accepting vague standards. An intangible to be considered when developing design standards is the explicit recognition that a hospital is a highly emotional place. It has proven beneficial to review with decision-makers how they should respond to, as the Danish architect Erik Asmussen7 says, “what happens here”.

Life-changing events and extremes of human drama call for non-technical qualities beyond competent infrastructure or corporate office quality standards. For example, depending on the specific client group, these questions have been posed:

- What kinds of connections do we perceive human beings seek with nature?

- Do hospitals share distinguishing qualities with other meaningful spaces, such as religious or academic buildings?

- How can these connections be made most effectively in a healthcare setting?

- What is the value of protecting these connections with standards?

- What is the cost of not making these connections?

- How and why should these qualities be expressed as design quality standards?

In particular, the client’s mission, vision and values statements are closely analysed to determine how these words can be translated into physical space, and why it is vital to minimise any gaps between espoused priorities and built reality. The consequences of ignoring this gap in terms of credibility with staff, patients and donors are assessed during the facilitated dialogue sessions.

|

Upper atrium of Colchester Regional Hospital in Truro, Nova Scotia (photo courtesy Farrow Partnership)

|

Create criteria for gap analysis

Jointly create criteria for a gap analysis diagnostic tool. The Balanced Scorecard aims to elevate design standards above the traditional intangible status of optional and arbitrary to the status of necessary and verifiable. Rather than accept vague aspirations such as ‘design excellence’ and ‘healing environment’, the scorecard provokes decision makers to measure the gap between meaningful criteria for their specific project and what is being proposed at each stage as the design progresses.

Apply scorecard tool

Use the scorecard tool to jointly monitor any ‘say-do’ gaps that may be identified by anyone at any point as the design progresses. The purpose of this step is to share responsibility among all project participants for ensuring that the built reality will be as inspiring as the words. The scorecard encourages candid conversations about how planning participants are doing, rather than potentially accepting lower standards or ignoring collective self-delusion.

Results

Overall, each of the respondents who participated in the Angus Reid research, “reflected favourably on their experience with Farrow Partnerships Architects’ step-by-step method for developing design quality standards”3.

All respondents characterised the design standards creation experience as “a learning process, rather than a buy-in process”. The research also found that: “What seemed particularly important to respondents was the ability of the process to accommodate a broader number of stakeholders in the planning and decision-making processes, as well as the ability of the process to organically generate consensus among a large group of stakeholders, even when a wide disparity of opinion existed to start.”

The following are a range of comments that were representative of those received. On ‘values’, one participant commented that it was: “a collaborative approach involving our organisation learning as much about ourselves as we did about the principles of design.”

Some of the intangible outcomes were identified as:

“...creating a great quality of life for staff ”

“...creating a buzz in the community”

“....people are happy to come here...it’s an uplifting place; it’s not just a hospital”

“...provide hope and inspiration”

“...a source of pride for our community”

“...a better frame of mind while administering care.”

With regard to the process, participants commented:

“The architect has a lot of ideas, but so does the owner. The design process involved a lot of back and forth, a sharing of ideas.”

“...this isn’t just getting a hospital built; this is a chance to step back and look at the ways in which we deliver healthcare.”

“...that iterative process was really important.”

And on value for money:

“I did not believe in the beginning that we could accomplish what we wanted to for patients staying within a budget that could be tolerated by the public purse. But guess what? We did it. And for cheaper than many other generic big-box hospital projects.”

|

|

Figures 4 & 5: The summaries of the significant results of the research indicate that most participants felt they had

benefited from the step-by-step learning process and had developed a sense of shared responsibility

|

Conclusions

Although there is evidence of global interest in raising healthcare design standards, advocacy alone is unlikely to result in significant change. This paper has presented the results of a standards development process, based on adult learning principles, that builds on a fundamental understanding of the nature of intangibles.

As the research by Angus Reid Strategies indicates, when participants become engaged in a step-by-step learning process, they develop a sense of shared responsibility for creating site-specific, meaningful standards. This learning process, based on dialogue and discovery, can be more effective than efforts to gain buy-in for preconceived standards. Decision-makers who are neutral, apathetic, or actively opposed to raising design quality can become sensitised to the impact of human centric design through the process of articulating standards. When these intangible qualities are captured in precise terms, such standards can be rigorously monitored using a balanced scorecard.

When ratings are reviewed with client groups at major milestones during the project, there is remarkable consensus regarding the appropriate number to be assigned to these intangibles on a scale of 1-5. Although there is no way to prove such numbers objectively, the exercise indicates that intangibles can be monitored effectively. Based on research in the field, the process of creating and applying effective design quality standards requires a willingness to challenge what constitutes a true healing environment.

Meaningful terms of reference, developed and refined through facilitated dialogue with each unique client group, are the foundation for meaningful standards. Each project has unique design priorities and sensitivities that make their standards, and therefore their hospital, come alive.

Authors

Tye Farrow, BArch, MArch UD, OAA, MAIBC, NSAA, NAA, FRAIC, senior partner, Farrow Partnership Architects, Toronto, Canada

Sharon VanderKaay, BSc Design, ASID, director, knowledge development, Farrow Partnership Architects, Toronto, Canada

References

1. Experts call for action on design quality. World Health Design, October 2008, p9.

2. Rochon L. Why is hospital design so unhealthy? The Globe and Mail, 15 December 2007.

3. Angus Reid Strategies. In-depth interviewing qualitative research project: Evaluating the Farrow model of the design standards creation process. 27 May 2009.

4. Lev B. Intangibles: Management, measurement and reporting. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2001.

5. Blair MM, Wallman SMH. Unseen wealth: Report of the Brookings Task Force on intangibles. Washington DC: Brookings Institute Press; 2001.

6. Knowles MS, Holton EF III, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Maryland Heights MO: Elsevier; 2005.

7. Coates GJ. Erik Asmussen, Architect. Stockholm: Byggförlagte; 1997.

|

1.1.jpg)

|