Children's Hospitals: Restore, revive

|

The Meyer Hospital brings together advanced technology and environmental sustainability in a unique setting

|

When CSPE and Anshen + Allen were asked to convert a former TB institution into a children’s hospital, the result combined old aesthetics with state-of-the-art modernity. Cristina Donati reports.

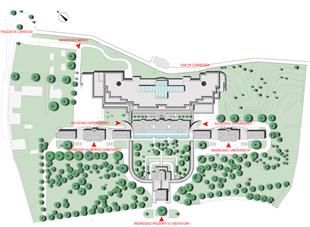

The Meyer Hospital in Florence brings together advanced technology and environmental sustainability in a unique setting – a 1930s villa set in a protected parkland of mature trees, surrounded by the renowned Florentine hills. The site demanded that its environmental and cultural heritage be transformed and updated with continuity and innovation; architects CSPE and Anshen + Allen brought together these contrasting aims in a mimetic building, embedded in the hillside, that integrates old and new, creating synergies between the original Ognissanti Villa, the landscape and a new pavilion.

Conceived as a piece of ‘land-art’, the new architecture, observed from above, shows an innovative topological approach that harmonises the building morphology with the contour lines of the hill, making it appear as a natural element of the land. Despite its size (76,598m3), it blends in with the lush hillside thanks to a strong environmental strategy. The three floors are tapered and staggered, creating overhangs with large, landscaped terraces crowned by a green roof that offers spectacular views of Florence.

The hospital entrance is a three-storey traditional building that has been accurately restored. The reason, explains CSPE director Romano Del Nord, is that “we wanted to create a memory of the past while reducing the stressful impact of a typical hospital structure.”

Arrival into the hospital has been diluted through layers of accessibility. Going through the main entrance, one enters a glazed passageway that threads through a ‘healing garden’ and then into the generous atrium space that stitches together the old and the new.

|

The Serra (Italian for Greenhouse), which contains the atrium and main reception desk, has a structure that echoes the surrounding trees

|

Remodelling for today’s needs

Villa Ognissanti was originally built in 1930 as the first institution in Florence for the treatment of tuberculosis. Its plan, based on a triple-block design, wasn’t easy to alter to meet the needs of a modern-day hospital. Nevertheless, the new design was able to retain the cultural heritage of the old structure and integrate distinct and separate functions into the renovation of the three blocks.

The east wing hosts the university and research unit; the west wing, the outpatient facilities; and a central block houses the administrative department. The elevations have been painstakingly refurbished in accordance with the principle of restorative conservation, with the exception of the central facade, which is screened by a large greenhouse that floods the new atrium with sunlight. The traditional Tuscan architecture of the villa is enhanced by new technology, which emphasises efficiency and quality of care.

The hospital’s strength lies in the way in which it has overhauled not only the technology, but also the culture of hospitalisation, without compromising the identity of the new architecture. Its design was conceived as a unitary system of green areas, where technology and materials bring about the sustainable balance of structure, technology and environmental sensitivity.

In 2000, the project received funding from the EU to accomplish the best sustainable procedures and promote energy saving. A number of eco-friendly solutions have also revive been implemented both in the renovation of the villa and in the new pavilion. Villa Ognissanti features a new ventilated roof, shading devices and facade grills that favour natural ventilation.

The most impressive element, however, is the bio-climatic entrance hall called the ‘Serra’ (greenhouse) that acts as the public face of the hospital. This curved triple-height space, attached to the central wing of the villa, is an innovative atrium that turns sustainability into a language of materials, textures and colours.

The laminated wood pillars reflect the shape of the surrounding trees, and incorporate building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) that enhance the aesthetic of the fac¸ade, filter natural light and produce electricity up to 31 kWp. The green roof, besides being a sheltered, healing garden for patients, provides an insulated covering which naturally lowers the temperature inside the hospital by several degrees and plays a leading role in the energy balance of the building.

Conical skylights, called ‘cappelli di Pinocchio’ (Pinocchio’s hats – the children’s story inspired many design details), pierce the roof and together with 47 ‘solatubes’ provide the interior with natural lighting. Quality of light and lighting play a fundamental role in environmental and psychological wellbeing, and good climactic conditions as well as the orientation of the building maximise natural light and the visual relationship with the landscape. This allows patients to experience the changing of light and the passage of time and of the seasons, helping to reduce any sense of isolation.

Materials, light, visual art and the landscape perception create a harmonious and positive physical, as well as psychological, atmosphere which improves the culture of the children’s hospital thanks to criteria that extend beyond a strictly functionalist agenda. Massimo Resti, head doctor of paediatric medicine, agrees: “Colour, light and contact with the landscape maximise privacy and safety without compromising on the high level of care.”

|

A glazed passageway leads to the atrium with its integrated photovoltaics on the exterior

|

Function and orientation

Thanks to a large parking area, the entire hospital campus has been conceived as a single car-free system of green areas where wayfinding is a constant priority. Two glass-enclosed staircases link the old villa with the new circulation, which is divided according to users – staff, visitors, patients and goods. Each level hosts compatible functions: the basement houses plant as well as a multicultural spiritual space; on the ground fl oor are outpatients departments, first aid and imaging, the reception area, shops and a cafeteria; on the first floor there is an operating area with seven theatre suites and intensive, specialised care units.

The majority of the patient-focused areas are on the second floor, with some on the first floor (polifunctional intensive care, infectious diseases and the isolation ward). The ward arrangement has been designed to allow future flexibility and adaptability. Patients’ rooms are concentrated on one side, with medical services on the other side. This layout creates a central distributive space of variable width, in which there are four work areas for the staff. It is a ‘cluster’ scheme, with a curving circulation spine that removes the oppressive feeling of old-style narrow institutional corridors and offers a more open and friendly way to live and work.

The innovative ward layout creates two particular areas by the patient room: an exterior area, delineated by the overhang, which can be used as a protected open space; and an interior space overlooking the distribution area, offering a secluded space and a meeting point for parents and doctors. All rooms have double windows, one that overlooks the landscape, and another that enables staff to discreetly oversee the patients. The rooms (30m2 for the double room, 24m2 for the single) are equipped with sofa beds to allow parents to stay with their children.

“The innovative design strategy implemented for the new Meyer has fi lled in the gap between technology and humanisation,” explains Monica Frassineti, the hospital’s chief executive doctor. “The result is a stress-free environment with many child-friendly features.”

|

| A national research team investigated strategies to prevent environmental stress and maximise psychophysical wellbeing conditions in hospitals |

Research-driven design

Anshen + Allen’s Derek Parker and Felicia Cleper Borkovi together founded The Children’s Hospital Explorers (CHEX) to encourage a multi-disciplinary discussion about the design of the built environment for sick children and their families. CHEX aims to understand more about the link between facility design and quality improvements for paediatric patients, families, and staff: Parker and Cleper Borkovi believe that children’s hospitals should be “caring and supportive of the individual child/family, non-trendy, and timeless”.

Furthermore, they say that “the children’s hospital environment should be safe and secure, and be a backdrop for varying ages and cultures. The environment should not only allow children to arrange their space to suit their individual needs, but it should be designed to encourage it.”

CSPE director Romano Del Nord is a leading theorist on evidence-based design and chair of TESIS, the Florence Inter University Research Centre for Systems and Technologies in Healthcare which, since 1992, has been examining evidence-based design with particular attention to children’s hospitals and their quality of care. To support and foster the Meyer design, Del Nord coordinated a national research team investigating all possible strategies to prevent environmental stress and maximise psychophysical wellbeing conditions in hospitals. The results of this research were subsequently published in Environmental Stress Control in Children’s Hospital Design (Milan 2006, edited by Romano Del Nord).

Together, CSPE and Anshen + Allen led an interdisciplinary design team made of consultants in environmental psychology, sociology, ergonomics, landscape architecture, visual art and health management and implemented their findings into the design of the Meyer Hospital. The innovative methodology used the best evidence regarding light, sound, art, air quality, colour and nature. As a result, the interiors have been enriched with play corners, recreation areas, colourful signage and works of art everywhere – designed to make the children feel more at home and less like they’re in a hospital.

“The suggestions expressed by 500 Florentine children interviewed during a conference naturally became part of the brief, and turned the hospital into an ideal place for childcare, where visual art and interior design are child-focused,” recalls Carlo Barburini, chair of the Meyer Foundation, which was set up in 2000 to provide support and monitoring for the development of the project. The Foundation endeavours to serve as a point of reference for all the professionals and technicians who are responsible for ensuring the best possible quality of life for children, as well as the most advanced forms of treatment. “The suggestions expressed by 500 Florentine children interviewed during a conference naturally became part of the brief, and turned the hospital into an ideal place for childcare, where visual art and interior design are child-focused,” recalls Carlo Barburini, chair of the Meyer Foundation, which was set up in 2000 to provide support and monitoring for the development of the project. The Foundation endeavours to serve as a point of reference for all the professionals and technicians who are responsible for ensuring the best possible quality of life for children, as well as the most advanced forms of treatment.

“Meyer is the original outcome of a long-standing Italian tradition of childcare: a tradition that believes in children’s dignity with a commitment to the highest levels of care,” says Meyer’s CEO Tommasso Langiano. “The hospital is designed and built to maximise aesthetics, technology and the environment to ensure the wellbeing and comfort of patients, families and staff.” It is also the result of an inter-disciplinary team sharing the challenge to create a patient focused facility – one of the first successful examples of a form of experimentation whereby the architecture interprets the perception of space through infant psychology in order to create a true hospital for children: a hospital for the future.

Cristina Donati is an architectural writer and an architect with CSPE

Meyer Children’s Hospital, Florence

|

| Opening date: |

December 2007 |

| Project budget: |

€57m

|

| Client: |

Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Meyer |

| Architects: |

CSPE (Centro Studi Progettazione Edilizia), Florence, and Anshen + Allen, San Francisco, USA |

| Project manager: |

Paolo Felli, CSPE |

| Main contractor: |

Itinera, Gemmo Impianti, COGEPA |

| Environmental psychologists: |

Prof Mirilia Bonnes, Marino Bonaiuto |

| Healthcare specialist: |

Prof Mario Zanetti |

Structural engineer:

|

A&I (Architetti e Ingegneri Associati); |

| Studio |

Tecnico Chiarugi |

Mechanical engineer:

|

CMZ (Cinelli – Marazzini – Zambaldi) |

| Electrical engineer: |

Studio Lombardini Engineering |

| Environmental sustainability programme: |

Centro ABITA |

|

1.1.jpg)

|