A scientific approach to assess impact

The opening of a continuing care and rehabilitation facility in Toronto offers an opportunity to undertake a systematic post-occupancy evaluation project – one that focuses on the interplay of mental, social and physical health rather than operational outcomes

Celeste Alvaro, PhD, Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation and Ryerson University, and Cheryl Atkinson, BArch, MRAIC, OAA, Ryerson University

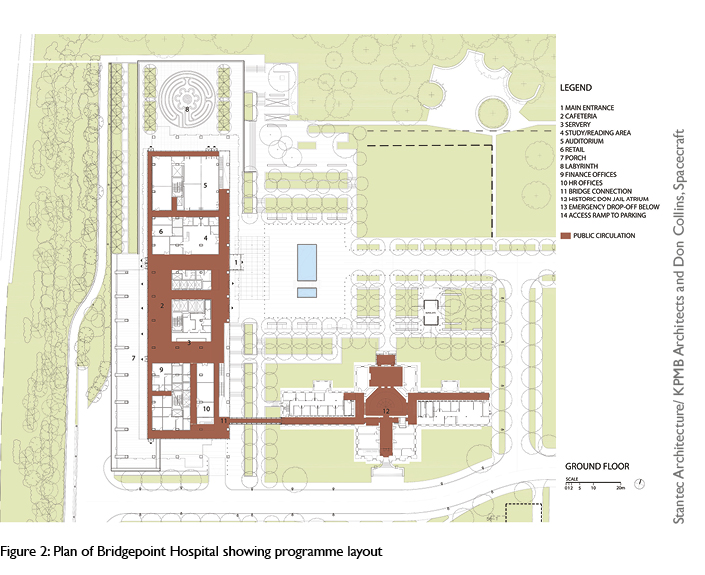

Bridgepoint Hospital is a new 404-bed complex continuing care and rehabilitation facility with the largest cohort of complex continuing care and complex rehabilitation patients in east Toronto, Canada. Patients at Bridgepoint Hospital have multi-morbidity (many health issues), often accompanied by psychological and social issues that affect health outcomes and quality of life.1,2 The new hospital – designed by Stantec Architecture/KPMB Architects (planning, design and compliance architects) in joint venture, and HDR Architecture/Diamond Schmitt Architects (design, build, finance and maintain architects) – was purposefully designed to address the needs of this patient population.1

In 1860, a 100-bed house of refuge was opened on the site. Over the ensuing years, various new and repurposed facilities evolved to address healthcare challenges of the time, including a smallpox hospital, an isolation hospital, a regional centre for polio and a provincial centre for complex continuing care for people living with HIV/AIDS.3 The new hospital replaces a deteriorating (both in form and function), architecturally distinct half-round facility that was built in 1963 to meet the growing need to support people with long-term illnesses. Care provided in this facility had shifted from long-term care to complex continuing care and rehabilitation and it was branded as Bridgepoint Health in 2002. The new Bridgepoint Hospital, opened in 2013, has been branded as Bridgepoint Active Healthcare.

This research examines the impact of architectural design on psychosocial wellbeing (ie psychological wellbeing as a function of interactions with the social environment) and health in the context of the Bridgepoint Hospital redevelopment. This unique opportunity for a naturalistic quasi-experiment allows for the comparison of consistent patient, staff, and organisational performance outcomes based on design elements of the new facility design against their counterparts in the old facility, with a constant comparator. Three buildings are at the focus of this research: the in-situ historic building (occupied until April 2013), the new build (occupancy effective April 2013), and a complex continuing care and rehabilitation facility with similar patients, slated to undergo redevelopment in the coming years.

Background and rationale Background and rationale

Worldwide, chronic disease (eg long-term progressive illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease, osteoporosis, or neurological diseases that require ongoing management for which there is no cure) is considered to be one of the most pressing health issues of the 21st century.1,2 Public health advances together with an ageing population have contributed to an increased prevalence and burden of chronic disease,4 resulting in an expanding crisis within the healthcare system. While some individuals with chronic disease manage with minimal health intervention, growing proportions of individuals are complex and require ongoing care. Individuals with complex chronic disease (CCD) have frequent or lengthy stays in the hospital5 and face considerable challenges in adapting to changes stemming from their illness.6-8

Over and above the physical health conditions, individuals with CCD experience considerable psychological distress resulting from the erosion of their self-concept as they adjust their role from that of a healthy individual with a normal life to that of a patient with a debilitating disease requiring long-term to permanent medical care.9 With the acceleration of population ageing over the next three decades,10 the complex continuing care and rehabilitation patient population will be the norm rather than a niche patient population.

The chronic disease crisis is global,2 and as care needs shift from acute to chronic disease management, the ability to accommodate the current and future cohorts of patients with the current infrastructure is diminishing.11,12 Knowledge of design that leads to a high-performance healthcare facility for the patient of the future is limited. The shift in care needs, coupled with the projected growth of capital investments in healthcare facility redevelopment presents an opportunity to develop new architectural paradigms to optimise health outcomes for this emerging patient demographic. As evidence shows that psychosocial support and adaptation can influence health outcomes,13 psychosocially supportive or salutogenic design (ie design to promote positive psychological and social wellbeing)14 is increasingly relevant in the planning, design, and construction of healthcare facilities for this patient population.

Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is the systematic evaluation of newly constructed buildings after they have been occupied for at least one year.15,16 POE of hospital buildings emerged in the 1990s to assess the effects of healthcare environments on safety, efficiency, and clinical outcomes17 with limited focus on outcomes related to psychosocial wellbeing.17-19 Despite the acknowledgement of POE as standard practice,20 and the burgeoning literature on evidence-based design, there are very few industry standards, guidelines or established methodologies for conducting POEs of healthcare facilities.21-23 Among the published research, there is variable methodological rigour and limited comparability of measurement and outcomes across POEs.

Moreover, POEs often lack a true pre-test comparison, which is commonly attributed to the construction or redevelopment of a facility to serve a different purpose than the original facility.

To date, relatively few research studies have compared pre- and post- construction facilities to assess the impact of design elements on health outcomes, thereby limiting the ability to attribute causality of outcomes to differences in architectural design. In addition to these shortfalls, POEs are often conducted by architectural firms and/or healthcare organisations with a vested interest in identifying successful outcomes associated with the design and investment rather than an independent research team to ground the evaluation in science. 20

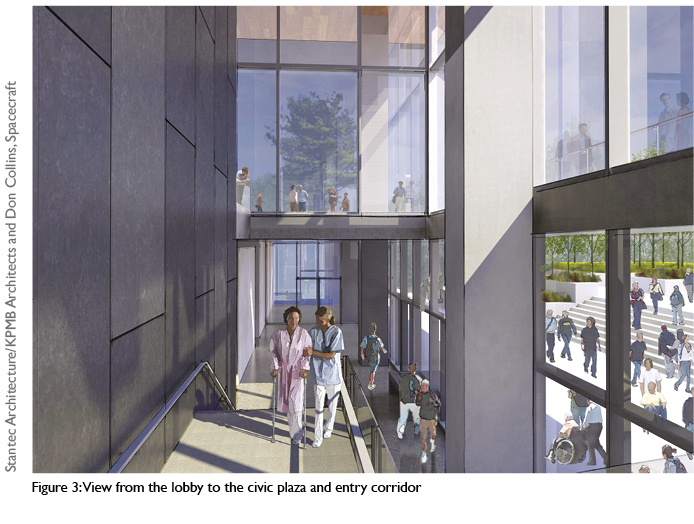

Design intentions for Bridgepoint

With an awareness of the evidence on salutogenic design14 and the therapeutic benefits of nature,19,24 the architects sought to “enhance quality of prolonged life”25 and “restore courage and lift spirits” through the “power of good design”.26 The central design intentions were to create an environment of wellness by enhancing the connection to community, nature and the urban environment, providing opportunities for social interaction and inspiring physical activity and health. According to the architects, “the project is as much about city-building and engagement with the community as it is about creating an architecture of wellness”.25

These intentions are evident in the design through specific elements described below.

Communal and social spaces: A greater quantity and variety of lounge, retail, and public spaces are provided in the new hospital. They are typically positioned off circulation hubs to facilitate impromptu encounter and exchange and offer destination points to encourage patient mobility. ‘Stacked neighbourhoods of care’25 reminiscent of a vertical city are designed with a variety of material characters, locations, orientations and views to enhance desirability for activity. Examples of these design elements include:

• communal and dining spaces located on each floor off the elevator lobby

• public spaces at grade with amenities (eg auditorium, library, pharmacy, coffee shop, urban porch25 connected to the public park and street access

• outdoor south facing terrace, café and ‘sky lounge’ on the top (10th) floor with distant views to the lake and city

• cybercafé located on the 5th floor (mid-building).

Physical and visual connection: Expansive glazing and passages from both rooms and corridors connect the patients to both the adjacent community and park both visually and physically. Its connection to the adjacent community is balanced with a conscious and constant connection to the park to derive “therapeutic benefits of nature”.25 Examples of these design elements include:

• use of glazing configured to draw patients to near and distant views of the lake, city, park and community

• main internal corridors and elevators terminate in views, exits and entrances to the exterior

• programming at grade encourages community interaction.

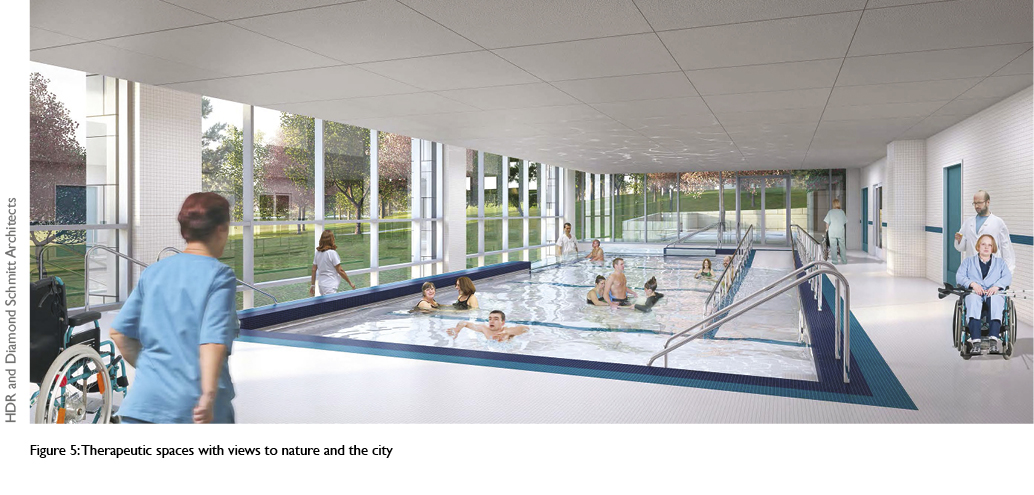

Therapeutic, respite and contemplative spaces: More and varied spaces that allow for rehabilitative and restorative therapy, quiet contemplation and respite were incorporated to foster calm and reduce anxiety. The new hospital includes an increased amount of private space for patients and quiet indoor and outdoor lounge spaces. The generous spatial dimensions of rooms and corridors eliminate clutter and the sense of congestion and noise of the original building. Examples of these design elements include:

• single and double rooms, replacing four beds per room

• quiet contemplative gardens at various levels

• clear wayfinding and circulation corridors

• natural materials and colours (eg wood ceilings)

• lounges and therapeutic spaces with views to nature and the city

• outdoor labyrinth.

A rigorous approach to POE A rigorous approach to POE

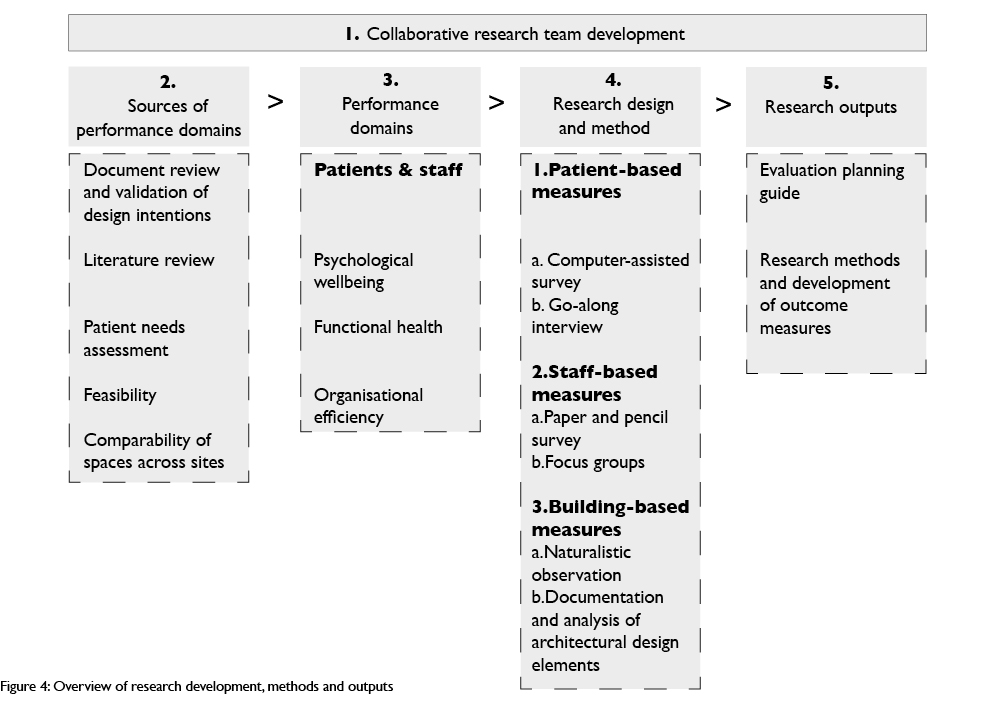

The design intentions of the new hospital informed the theoretical basis for development of methods and measures for the POE. The overarching goal was to select outcomes that could be attributed, directly or indirectly, to the building design with consideration of the factors that might moderate the effect of design on psychosocial and health outcomes. As outlined in Figure 4, our approach to POE can be summarised according to five steps: collaborative research team development, review of sources to establish performance domains, selection of performance domains, development of the research design and methods, and consideration of research outputs. Each component is described below.

1. Collaborative research team development: This research represents a unique interdisciplinary, intersectoral collaboration consisting of academic researchers, high-level government decision makers, principal architects in the field of healthcare facility design and healthcare directors. The full research team of nine core members has contributed to the development of the research questions and the consideration of outcomes to be assessed across methods in the research. All stakeholders have a vested interest in the development of consistent methods and measures to assess the impact of healthcare facility design on health, particularly as related to this facility. In contrast to POEs conducted by architects or hospital personnel,20 this collaboration was initiated by an independent research team with specialised theoretical and methodological expertise. This ‘one step removed’ aspect of the research has fostered the engagement of architects, stakeholders in executive/management roles at hospitals and their clients (patients) in the common goal of advancing research in the evaluation of healthcare facility design. Ongoing monthly meetings with opportunities for consultation and contribution fostered the active engagement of the architects and healthcare leaders and scientists throughout all phases of the research. This POE serves as a demonstration project for POEs across the province through the active engagement and participation of a senior architect within government.

2. Sources of performance domains: Sources used to identify the healthcare facility performance domains and resulting methods that are being used in the study are described below. The steps were:

Document review and validation of design intentions: A review of redevelopment documents (eg the building programme, architectural design intent, building budget, models of care, blueprints, meeting minutes, briefing notes and user group summaries) provided context for the logic and decisions related to the building design. A stakeholder focus group consisting of architects, hospital administrators and redevelopment officers involved in various stages of the design process was convened to validate the design intent. The architects’ direct input in translating the design intentions, the design features, and hypothesised outcomes, together with the hospital administrators’ input on the relevance and importance of particular outcomes, enabled the development of methodological and measurement tools unique to the POE.

Literature review: The impact of the built environment on psychological, social, and physical health has been widely documented14,19,27-33 and is fundamental to the study and practice of architecture.17,18,34 A literature review and synthesis was conducted to identify design elements that contribute to psychosocial wellbeing and health more generally, and to develop measures of relevance to the salutogenic design of the new Bridgepoint Hospital.

Patient needs assessment: Chronic conditions are affected by several factors including physical health,35 personal characteristics and socio-demographics,4 mental health36 as well as health and social experiences.4,37 These dimensions formed the basis of an extensive patient needs assessment conducted at Bridgepoint Hospital prior to moving to the new facility. An emergent theme in the assessment results was the patients’ perceptions of how the building design (eg access to daylight and views, fresh air, social spaces, wheelchair mobility, wayfinding and privacy) influenced their experience, rehabilitation, and associated health outcomes.6-8

Feasibility: Using the evidence generated from the document review and validation, the literature review, and the patient needs assessment, the team selected measures on the basis of: (a) measures that are most directly relevant to the design intentions of the new facility, (b) measures for which there was a basis for comparison between the existing facility and new facility, and (c) measures that are readily available and of high quality within hospital databases.

Comparability of spaces across sites: Spaces were selected on which there was a basis for comparison and/or contrast across the existing (old) new and comparison facility.

3. Performance domains: The performance domains and associated measures were selected to be consistent with the design intentions for the new Bridgepoint Hospital, to make a novel contribution to the evidence-based design literature, and to be relevant to complex continuing care and rehabilitation. Three performance domains were selected: Psychosocial wellbeing (eg depression, social connectedness, sense of community, motivation, mood, stress reduction and coping), functional health (eg pain, mobility), and organisational efficiency (eg falls, infections, medical errors) across patients and staff.

4. Research design and methods: Overall, this research is based on a pre-post test quasi-experimental design with a comparison group38 to compare patient, staff and organisational outcomes across the earlier facility, the new facility and a comparison facility. This research design enables evaluation of interventions when randomisation is not possible, enhances the ability to infer causality between an intervention and an outcome, and enables the comparison across facilities over time.

Several quantitative and qualitative methods were embedded within the overall pre-test, post-test quasi-experimental design. Methods were selected on the basis of the research questions to be addressed, the construct to be assessed and the desired conclusions to be made. Whereas quantitative methods allow for the attribution of causality and enable generalisation, qualitative methods allow for the contextualisation and documentation of the lived experience. The selected methods enable the assessment of both anticipated and unanticipated uses and consequences of the building design.39,40

The pre-test sample includes patients, staff, and the buildings at the earlier Bridgepoint Hospital and the similar comparison facility West Park Healthcare Centre (August 2012–February 2013). The post-test sample includes both patients and staff. Pre- and post-test groups are matched at the data analysis phase on the basis of medical conditions (patients), complexity of illness (patients), employment type (staff) and socio-demographic variables (eg socio-economic status, age, cultural background) of patients and staff. In addition to utilising standardised measures, other measures were uniquely created for this research to ensure relevance to the context and study objectives. The research protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Joint Research Ethics Board (JREB) of Bridgepoint Health/West Park Healthcare Centre/Toronto Central Community Care Access Centre/Toronto Grace Health Centre.

There were three patient-based research methods. First, computer-assisted survey examined the experience of the building design, psychosocial wellbeing and perceived health of patients. Data was collected via an interview format created using the Empirisoft Media Lab software platform, allowing for presentation of images, randomisation of question order, visual response options and direct entry of responses on the computer.41 Measures included the experience of the building, its setting and designated spaces; sense of belonging;42 perceived improvement;43 satisfaction, mood, wellbeing, and affective reactions to various spaces in the hospital (changes in behaviour such as increased or decreased uses of various spaces), changes in emotional state (eg increased or decreased states of calm), and perceptions of room or space character (eg cheerful, contemplative, calming, exciting, depressing, stressful). Participant characteristics, psychological traits such as outlook on life44 and socio-demographic information (eg age, gender, cultural background) were also included in the survey.

Second, go-along interviews provided context and further understanding of the patient experience; this research component was led by Dr Paula Gardner. The go-along interviews combine focused interviewing with participant observation wherein the researchers accompanied participants on their natural outings and actively explored the physical and social practices by asking questions, listening, and observing45 while capturing visual (photographs), textual (field notes) and auditory (audio recording) data. This method is effective for studying the implications of place on health and wellbeing.46 In this study, patient go-along interviews involved guided tours of ‘day-to-day living’ with prompts from an interviewer to explore perceptions, experience and knowledge related to the design of the facility, with a particular focus on mobility, ease of navigation and self-efficacy.47,48

Third, existing clinical and administrative data sources were used to examine differences in functional health and organisational efficiency outcomes related to patients while controlling for patient characteristics. A randomly selected subset consisting of 220 cases from patient administrative databases was extracted at each site at pre-test (spring 2013) and post-test phases (spring 2014). Measures included functional health outcomes (eg mobility, pain, level of physical function, stability of condition) and organisational efficiency and quality outcomes (eg discharge rates, length of stay, critical incidents such as falls and infections) for patients.

There were three staff-based research measures. First, a paper and pencil survey examined the experience of the building design, psychosocial wellbeing (eg burnout, satisfaction, interactions with colleagues), and functional health (eg, ability to carry out their work) of staff. To allow for mass distribution and self-completion, the staff survey was administered in paper and pencil format. Key measures mirrored those in the patient computer assisted survey with slight modifications for relevance to staff. The survey also captured psychological traits and information relating to socio-demographics (eg age, gender, cultural background).

Second, focus groups with staff (eg clinical, executive/administration and facilities management) were conducted at each site at the post-test phase to provide context for the staff survey data and further understanding of the staff experience of the facility design and its implications for their work and wellbeing. Third, as a parallel to the patient database extraction, existing administrative data sources were used to extract information on staff health (eg employee turnover, sick days, critical incidents, workplace injury).

There were two building-based research measures. First, naturalistic observation, whose purpose is to examine the usage patterns of designated indoor and outdoor spaces by patients, staff and visitors. Naturalistic observation offers the unobtrusive collection of in-depth information about behaviour such as social interactions, activities and patterns of use, without disrupting naturally occurring behaviour and/or interaction. Selection of spaces to be observed was based on time of day, likelihood of use and design intentions. Six spaces were observed at each site at both pre- and post-test phases. Our team has developed a customised application for tablets (eg iPads) to capture the space, time of day, users of the space, field notes and observer narratives, contextual factors, as well as expected and unexpected uses of space. Second, the architectural design elements were documented and analysed, led by Cheryl Atkinson. The purpose of this documentation was to compare the architectural design elements of the spaces under study (based on form and function) across the old, new and comparison hospitals.

The documentation and analysis of design elements across facilities was achieved through the visual comparison of building plans, functional and relational diagrams, and section plans. This analysis was supplemented with photographs of designated spaces and the use of software to model daylight penetration. Documented components include:

• type of space

• area and proportional differences in rooms and spaces

• organisational patterns of movement and circulation

• sectional organisation of public spaces

• plan relationships (proximities and adjacencies) of rooms and spaces

• travel distances (for patients and staff) to various activities and functions

• natural light quantity, location orientation and type (direct and indirect)

• acoustic conditions (actual noise quantity versus perceived noise quantity)

• window locations in the building and site

• window proportion, scale, dimension and configuration on wall

• material type, texture and colour.

Following the separate analyses of data within a given method, interpretive synthesis across methods and content analysis were used to triangulate and synthesise findings. The objectives of the interpretive synthesis is to identify common themes, factors and explanations across methods to inform knowledge translation and decision making support to knowledge users.49,50 Analyses include pre- and post-test comparisons between patients and staff within a facility (Bridgepoint Health or West Park Healthcare Centre) and across facilities (Bridgepoint Health versus West Park Healthcare Centre).

There are some limitations to using a pre-test post-test quasi experimental design. The most significant limitations are a consequence of: (1) a lack of randomisation and (2) pre-existing differences across comparison facilities (eg differences in physical elements of the site, differences across patients and staff) and contextual factors (eg organisational changes, unexpected outbreaks, accreditation activities, functional programming). To address these limitations, the differences across facilities have been documented and included in the data analysis to assess their impact on the results.

5. Research outputs: Results of this research will inform the development of a healthcare facility design evaluation planning guide. The planning guide will include tools, templates, and standards for research design, methodologies, and measurement of health outcomes to be applied to future hospital redevelopment projects.

Discussion

The redevelopment of Bridgepoint Hospital offers the opportunity to assess the impact of architectural design on psychosocial wellbeing and health via the comparison of outcomes at a purpose-built facility against its predecessor, on the same site and with a control facility of similar staff and patients. Akin to best practice guidelines in healthcare delivery, this research offers insight into improved practices and enhanced rigour to assess design aimed at improving the psychosocial wellbeing and health of a complex continuing care and rehabilitation patient population. This research is the largest systematic POE in Canada. It represents a marked departure from the existing studies in this domain that tend to focus on operational, functional, and organisational outcomes rather than the interplay of mental, social and physical health within a complex care and rehabilitation patient population. Over and above the value of the project as an exemplar for standardised and mixed methodologies in the evaluation of healthcare facility design, it represents a unique approach to evaluation that uses the design intentions as a theoretical basis on which to measure outcomes.

In Canada, POEs of facility functionality are commonly included in the redevelopment plan but typically they are not designed as systematic research studies. The movement towards evidence-based design and increased need to demonstrate substantive outcomes related to capital investments has initiated a movement to incorporate facility evaluation from the beginning of the planning and design process.51-53

The expertise of our team and engagement of knowledge users will ensure a comprehensive, relevant and scientifically rigorous programme of research to improve decision making about strategic investments and policies related to healthcare facility design to improve health outcomes, and models of complex care and rehabilitation that include the built environment. On a smaller scale, results will be used to develop interventions related to design and the use of space at the new facility post-occupancy.

Beyond the Canadian context, this research is well positioned to contribute at an international level. Worldwide, healthcare planners are faced with the challenge of how to address the needs of this growing population in an era of deteriorating infrastructure and financial constraints. Key questions remain concerning how to make strategic investments in facility design. The development of consistent methodologies and measurement tools will generate the data that are necessary for comparisons across facilities. It will also enhance our understanding of the design elements that have the greatest impact on psychosocial wellbeing and health in general, as well as those that show greatest promise for specialised patient populations. This will serve the ultimate goal of improving wellbeing and health within a hospital context.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Capital Investments Branch of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, and Bridgepoint Health Foundation. The authors acknowledge the contribution of the core research team: Renée Lyons, PhD, Bridgepoint Chair in Complex Chronic Disease Research, TD scientific director, Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, professor, Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto; Paula Gardner, PhD, assistant professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, Brock University, research scientist, Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, assistant professor (status), Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Gregory Colucci, OAA, MRAIC, principal, Diamond Schmitt Architects; Clifford Harvey, OAA, MRAIC, senior architect, Capital Investments Branch, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; Tony Khouri, PhD, PEng, chief facilities planning & redevelopment officer, Bridgepoint Active Healthcare; Kate Wilkinson, MA, director, quality and patient safety, Bridgepoint Active Healthcare; Stuart Elgie, OAA, MRAIC, principal, Stantec Architecture; Mitchell Hall, OAA, MRAIC, principal, KPMB Architects. We also thank our collaborators: Janet Huber, chief business development and planning officer, West Park Healthcare Centre; David Garlin, planner, West Park Healthcare Centre; Tim Pauley, manager, research and evaluation, West Park Healthcare Centre; Alejandro Jadad, PhD, MD, chief innovator and founder of Global eHealth, University Health Network, Canada Research Chair in eHealth Innovation, University of Toronto. Special thanks also to the research assistants for their data collection and preliminary data analysis efforts, and to Kerry Kuluski, PhD and Michael Wasdell, MA for their review of various drafts of this manuscript.

Authors

Celeste Alvaro, PhD is research scientist at Bridgepoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, Bridgepoint Active Health, and adjunct professor, Department of Architectural Science, Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science, Ryerson University. Cheryl Atkinson, BArch, MRAIC, OAA is assistant professor, Department of Architectural Science, Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science, Ryerson University.

References

1. Walker D. Caring for our Aging Population and Addressing Alternative Level of Care. Report submitted to the Minister of Health and Long-term Care; 2011.

2. World Health Organization Preventing Chronic Diseases: A vital investment. Geneva: WHO; 2005.

3. Bridgepoint Active Healthcare. 2013 [Accessed 13 May 2013]. Available from: www.bridgepointhealth.ca/history

4. Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: Prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. European Journal of General Practice 2008; 14 Suppl 1:28-32.

5. BMA Science and Education. The psychological and social needs of patients. 2011 [cited 2011 April 1, 2011]; Available from: http://bmaopac.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/exlibris/aleph/a21_1/apache_media/G8KXL7EIUQNLK7RQTQ5EP9ERF4AF1L.pdf

6 Kuluski K, Hoang S, Schaink AK, Alvaro C, Lyons RF. The care delivery experience of hospitalized patients with complex chronic disease. Health Expectations. in press.

7. Kuluski K, Schaink A, Lyons R, Alvaro C, Bernstein B (eds). The Face of Complex Chronic Disease: Understanding the patient population at Bridgepoint Health. Bridgpoint Collaboratory for Research and Innovation, Toronto, Ontario; 2012 May.

8. Kuluski K, Bensimon CM, Alvaro C, Schaink AK, Lyons RF, Tobias R. Life interrupted: A qualitative exploration of the impact of complex chronic disease on the daily lives of patients receiving complex continuing care. Illness, Crisis, & Loss. in press.

9. Yaghmaie F, Khalafi A, Majd H, Khost N. Correlation between self-concept and health status aspects in haemodialysis patients at selected hospitals affiliated to Shaeed Beheshti University Medical Sciences. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2008;13(3):198-205.

10. Statistics Canada. A Portrait of Seniors in Canada. 2006. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-519-x/89-519-x2006001-eng.pdf

11. Harvey C (ed). Health Capital Built Infrastructure Research: Roundtable meeting of the Post-Occupancy Evaluation Think Tank. University of Toronto; 26 September 2012.

12. Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal. Five-year investment plan will help ensure high-quality services for Ontarians. Press release; 25 May 2005. Available from: http://news.ontario.ca/archive/en/2005/05/25/FiveYear-Investment-Plan-will-Help-Ensure-HighQuality-Services-for-Ontarians.html

13. Schüssler G. Coping strategies and individual meanings of illness. Social Science & Medicine 1992; 34(4):427-32.

14. Dilani A. Psychosocially supportive design: A salutogenic approach to the design of the physical environment. Design & Health Scientific Review. 2008; July:47-53.

15. Preiser WFE (ed). Health Center Post-occupancy Evaluation. Towards community-wide quality standards. Sao Paulo, Brazil: NUTAU/USP; 1998. .

16. Preiser WFE, Vischer JC. Assessing Building Performance. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005.

17. Ulrich RS. Effects of interior design on wellness: Theory and recent scientific research. Journal of Health Care Interior Design 1991; 3:97-109.

18. Kagan AR, Levi L. Health and Environment – Psychosocial stimuli: A review. 2nd ed. Levi L (ed). London, New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press; 1975.

19. Ulrich RS. Biophilia, biophobia, and natural landscapes. In: Kellert SR, Wilson EO (eds). The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1993. p. 73-137.

20. Forbes I. Benchmarking for health facility evaluation tools. World Health Design 2013; 6(2): 50-7.

21. Victorian Government Health Information. Capital Development Guidelines; 2010. Available from: www.capital.health.vic.gov.au/capdev/PostOccupancyOverview

22. NHS Scotland. Scottish Capital Investment Manual – Project evaluation guide. 2012.

23. University of Westminister. Guide to Post Occupancy Evaluation; London: HEFCE; 2006. Available from: www.aude.ac.uk/info-centre/goodpractice/AUDE_POE_guide

24. Wilson EO. Biophilia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1984.

25. Award of Excellence: Bridgepoint Health. Canadian Architect. 1 December 2008.

26. Diamond and Schmitt to design new Bridgepoint Hospital. Canadian Architect. 18 October 2009.

27. Guiliani MV, Scopelliti M. Empirical research in environmental psychology: Past, present, and future. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2009; 29:375-86.

28. Kaplan R, Kaplan S. The Experience of Nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge: University Press; 1989.

29. Sundstrom E, Bell PA, Busby PL, Asmus C. Environmental psychology 1989–1994. Annual Review of Psychology 1996; 47:485-512.

30. The Center for Health Design. Definition of evidence-based design for healthcare. 2008 [cited 1 April 2011]; Available from: www.healthdesign.org/edac/about

31. Ruga W. Designing for the six senses. Journal of Health Care Interior Design 1989; 1:29-34.

32. Ulrich R, Quan X, Zimring C, Joseph A, Choudhary R. The Role of the Physical Environment in the Hospital of the 21st Century: A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Report to The Center for Health Design; 2004.

33. Joseph A. Health Promotion by Design in Long-term Care Settings. Concord, CA: The Center for Health Design; 2006.

34. Joye Y. Architectural lessons from environmental psychology: The case of biophilic architecture. Review of General Psychology 2007; 11:305-28.

35. Upshur RE, Tracy S. Chronicity and complexity: Is what’s good for the diseases always good for the patients? Canadian Family Physician 2008; 54(12):1655-8.

36. Fortin M, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, Soubhi H, Lapointe L. Caring for body and soul: The importance of recognizing and managing psychological distress in persons with multimorbidity. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 2007; 37(1):1-9.

37. Noel PH, Frueh BC, Larme AC, Pugh JA. Collaborative care needs and preferences of primary care patients with multimorbidity. Health Expectations 2005; 8(1):54-63.

38. Crano WD, Brewer MB. Principles and Methods of Social Research. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002.

39. Alvaro C, Atkinson C, Harvey C, Wilkinson K, Lyons RF, Gardner P et al. Assessing the Impact of Healthcare Facility Design on Health Outcomes: Implications for strategic investments in design. Canadian Institutes of Health Research Partnerships for Health System Improvement; 2012.

40. Alvaro C. Methods and Measures in the Evaluation of Healthcare Facilities: A scientist’s perspective. . Improving the post occupancy evaluation cycle: Taking the ‘P’ out of POE. Session on post-occupancy evaluation approaches and techniques: Perspectives from architects, owners and researchers. 20 February 2013.

41. Empirisoft. MediaLab software 2011.

42. Hagerty BM, Williams A. The effects of sense of belonging, social support, conflicct, and loneliness on depression. Nursing Research 1999; 48(4):215-9.

43. McFarland C, Alvaro C. The impact of motivation on temporal comparisons: Coping with traumatic events by perceiving personal growth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2000; 79:327-43.

44. Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology 1985; 4(3):219-47.

45. Kusenback M. Streen phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography 2009; 4(3):455-85.

46. Carpiano RM. Come take a walk with me: The ‘go-along’ interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health and Place 2009; 15(1):263-72.

47. Fliess-Douer O, van der Woude LH, Vanlandewijck YC. Development of a new scale for perceived self-efficcacy in manual wheeled mobility: A pilot study. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2011; 43(7):602-8.

48. Shumway-Cooke A, Patla A, Stewart AL, Ferrucci L, Ciol MA. Assessing environmentally determined mobility disability: Self-report versus observed community mobility. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2005; 53(4):700-4.

49. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009; 9:59.

50. Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. How can we synthesize qualitative and quantitative evidence for healthcare policy-makers and managers? Healthcare Management Forum. 2006: 27-31.

51. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care – Local Health Integration System (MOHLTC-LHIN). Joint Review Framework for Early Capital Planning Stages – Toolkit; 2010.

52. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Health Capital Planning Review; 2004.

53. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Ontario Health Capital Planning Manual; 1996.

|

1.1.jpg)

|