Ireland Report: A Tale Of Two Countries

Altnagelvin Area Hospital, Northern Ireland

|

| Cost: |

£150m |

| Client: |

Western Health & Social Care Trust |

| Lead Consultant: |

HLM Architects |

| Architect: |

HLM Architects/Hall Black Douglas Architects |

| Structural Engineer |

Doran Consulting |

| Quantity Surveyor and Planning Supervisor |

WH Stephens & Sons |

| Landscape Architect |

HLM Landscape |

|

|

Kathleen Armstrong explains how Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland – both surfi ng a wave of new economic opportunity – are approaching their ambitious healthcare building programmes.

He is a man with a vision. As head of Northern Ireland’s Health Estates Agency, John Cole is in charge of developing a healthcare estate that radiates design quality and provides healing spaces for a population of more than 1,700,000 people. His strategy is ambitious and challenging, but for those who want to be part of the creation of innovative health facilities, it is an exciting place to be.

Much of the healthcare stock in Northern Ireland is in real need of refurbishment. During the ‘Troubles’, the period of civil conflict that took place in the country between the 1960s and the mid-1990s, very little development took place. Most of it now needs to be replaced, and Cole is determined that the standard of design and quality remains high throughout the programme.

“That’s what attracts us to be involved,” says Justin De Syllas from Avanti Architects, the London-based firm that has worked on Belfast’s Grove Health and Wellbeing Centre in partnership with local architects Kennedy FitzGerald. The Grove is one of a range of primary- and community-care centres being developed throughout the country, and it is part of the reconfiguration of healthcare services that is going hand-in-hand with the redevelopment of facilities.

The three-storey building brings together primary care services – such as physiotherapy, podiatry, a small minor treatment suite, GP practices and social services – with a sport and leisure centre. Built on a long, thin site between a main road and a park, the building design aims to create a feeling of space, bringing in natural light through glazed walls and clear circulation routes.

A tiered system

There are five levels of healthcare facilities in Northern Ireland. Level 1 is the local GP and small surgery. At the next level up are polyclinics – serving 20,000-70,000 people, and bringing together diagnostics, consultancies and other services that can be dealt with out of hospital.

Level 3 is the community hospital providing respite beds, GP-managed beds and step-down care for people recovering from treatment in acute hospitals. Level 4 is the acute hospital, while Level 5 hospitals provide the centre for a particular specialist procedure or treatment such as cardiac surgery or brain surgery.

There is work going on throughout the country to develop and redevelop such facilities at all levels. Bids are also currently being considered for the redevelopment of acute hospitals such as Omagh Hospital and the £190m capital investment approved for the redevelopment of Ulster Hospital.

The £150m redevelopment of the Altnagelvin Area Hospital, an acute facility in Londonderry, was master-planned by HLM Architects in association with Hall Black Douglas Architects. As part of the development, the hospital’s original modernist tower block will receive a dramatic makeover, with new lighter, brighter wards and 100% single-bedroom accommodation.

The hospital’s new South Block, currently under construction, was one of the first major healthcare buildings in Northern Ireland to Altnagelvin Area Hospital, Northern Ireland to be procured under a scheme known as Performance Related Partnering (PRP). Developed by John Cole and his team to help ensure quality is maintained, design and construction teams are appointed on a partnership basis for more than one project, but have to demonstrate performance for each phase of their work to be able to ensure their appointment for the next phase.

Welcoming spaces

The recently completed mental health unit at Craigavon Area Hospital is another example of progressive design. The single-storey building creates a non-threatening, welcoming space for both patients and visitors, designed to support the therapeutic process. Outdoor spaces remain secure without the need for too many fences, while circulation routes have outside views and have been designed to ease orientation. At the same time, the geometry of the facility means that members of staff have the level of observation and control that they need, without making the building feel too dominating.

Craigavon Area Hospital Mental Health Unit, Northern Ireland

|

| Contract form |

GC Works |

| Project completion |

April 2008 |

| Cost |

£11.8m |

| Client |

Southern Health and

Social Care Trust |

| Architect |

David Morley Architects and Hall Black Douglas Architects |

| Structural Engineer |

Buro Happold |

| Services and environmental engineer |

Buro Happold |

| Landscape architect |

Livingston Eyre Associates |

| Quantity surveyor |

WH Stephens |

| Project manager |

Health Estates Northern Ireland |

| Main contractor |

Heron Bros |

|

|

Up until now, Private Finance Initiative (PFI) funding, where all or most of the funds for a particular project are provided, and controlled by, a private sector consortium, has been little used for healthcare building development in Northern Ireland.

However, it is now being brought in for some of the larger developments, including the redevelopment of Omagh Hospital. John Cole has adapted the PFI model for Northern Ireland in order to retain control of design quality: an architectural firm is selected through an initial competition to draw up an exemplar design of the facility; once the client’s needs have been established and the exemplar drawn up, the fi nal budget is established and contractors appointed.

Cole’s aim is to budget realistically from the start for the design and quality that need to be achieved for a project by putting the work in at the beginning, setting down the quality criteria that need to be achieved: “Contractors are not allowed to dumb these down,” he explains. The approach has been dubbed ‘smart PFI’ by the Royal Institute for British Architects (RIBA) and forms the basis of a model that the organisation has tried to promote throughout the rest of the UK.

Cole is also working on a combination of PFI and PRP that he calls “strategic partnering for PFI”, whereby two architectural teams will be appointed – one to work with the contractor throughout the project, and the other to remain with the client in order to ensure that the client’s needs continue to be met.

“The standard of design in the country is very good – and it’s all down to John Cole and the Health Estates Agency,” comments Christopher Shaw from MAAP Architects. “There is no one like him anywhere else in the UK.” Shaw’s practice is partnering with Donnelly O’Neill on the design and development of a children’s home in Newry. “It is easy to design an adult building and stick cartoons on it,” he says. “This will be a child-centred building, carefully choreographed around the lives of the child, parent and carer.”

South of the border

Quality is also high on the agenda in the Republic of Ireland, where the refurbishment, redevelopment and reconfiguration of services and facilities are also in full swing.

As in Northern Ireland, investment in healthcare facilities slowed down during the 1970s and 1980s, reflecting a downturn in the economy. But over the last ten years, the economy has boomed, along with government recognition of the need for capital investment to bring healthcare facilities into the 21st century.

The way that hospital services are being delivered is also changing, requiring new and/or reconfi gured estates. Acute services will be provided in regional hospitals, serving a wider area than the previous county hospital model, while out-of-hospital treatments and diagnostic tests are shifting into community hospitals, often housed in the county hospital facility.

This is also accompanied by the development of community nursing units, long-stay residential care facilities of around 50 beds each – smaller facilities located closer to the local community in the place of previous larger, more centralised care homes. As a model for these facilities, Brian O’Connell Associates, in partnership with Murray O´ Laoire Architects, has developed a design for St Mary’s Community Nursing Unit in Dublin that consists of a series of modules in which patient accommodation is designed around a series of courtyards. A second module provides the central foyer and community space, while a third houses support services.

Complementary private care

Another major government strategy is co-location. The healthcare system in Ireland differs in at least one major way from its neighbour to the north in that running alongside the public health system is a complementary system of private healthcare. Currently a certain percentage of patients treated in public hospitals are private patients. But the government’s co-location policy will see a number of private hospitals built on the same site as selected public hospitals.

In addition, a new wing will be constructed onto the public hospital for private patients who are currently treated in the state hospital, in order to free up beds for patients treated under the state system.

Further impacting on the design and planning of such facilities is the recommendation from the Strategy for the control of Antimicrobial Resistance (SARI) working group that new hospitals be required to have (and existing hospitals aim to have) at least 50% single beds, and, where there are multi-bedded rooms, that there be greater space between beds. Currently the typical ward in an Irish hospital has around 30-32 beds, including around four single-bedded rooms; the new policy will result in around 24 beds in the same space.

The new private hospital on the site of Dublin’s St Vincent’s University Hospital will feature 80% single beds. Designed by Scott Tallon Walker Architects, it will have a ‘hotel feel’ with views out over the bay and mountains, and will be constructed to BREEAM environmental standards.

|

Marymount Hospice, Republic of Ireland

|

| Contract form |

GCCC (New government contract form) |

| Project completion |

2010 |

| Cost |

€65m |

| Client |

Curraheen Hospital |

| Architect |

Donal Blake / Scott Tallon Walker |

| Structural engineer |

Arup |

| Services / Environmental Engineer |

Varming |

| Quantity surveyor |

O'Reilly Hyland Tierney |

|

|

|

Hospice-friendly hospitals

The creation of more space and the increase in single-bedded rooms is also driving the redevelopment of hospices. The Hospice Friendly Hospitals Programme – a collaborative initiative involving government, medical staff, architects and others involved in the provision of end-of-life care – has developed guidelines for the physical environment of hospice-friendly hospitals, recommending how to create a calm, reassuring environment for patients, families and staff with the use of space, colour, fabrics, views and the natural environment.

One of the first facilities to be developed using the recommendations from the programme is the Marymount Hospice at St Patrick’s Hospital. “The design is based on maximising the capabilities of the individual as their life is failing,“ explains architect Donal Blake from Scott Tallon Walker. Walkways will be designed for easy wayfi nding, with intermediary sitting areas. There are clear routes to bathrooms, and hoists over each bed. All bedrooms will have an east or west orientation, as well as balconies overlooking landscaped grounds. Courtyards and a rooftop garden will provide further access to nature. “The hospice will be a revelation in the way hospice care is delivered,” concludes Blake.

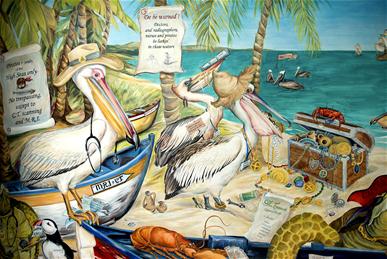

Art also has a signifi cant place in the design of every healthcare facility and is supported by the government’s Per Cent for Art Scheme, which allows public capital construction projects to ring-fence up to 1% of the budget for an art project. At the Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital in Crumlin, Dublin, murals of animals and aquatic scenes cover the walls in the new cardiac wing, the MRI room and the intensive care unit. Artist Lynne Misiewicz from Misha Design canvassed children, parents and medical staff to fi nd out what designs would help to provide a relaxed and friendly atmosphere and reduce children’s stress while in hospital.

The approval process

Design quality remains a key to healthcare facility development in the Republic. Until fairly recently, the quality of design was the main criterion for the selection of the design team, with fees being agreed later. Now, however, cost is included as a factor when a project goes out to tender. Most projects are procured through traditional methods, but more recently there has been a clear move towards design-build, where the design and construction are combined and paid for in a single tender process, particularly for projects where similar facilities are needed around the country. Each design will be adapted to suit the community and environment in which it is located.

|

| A mural at Our Lady's Hospital in Crumlin, Dublin, created by artist, Lynne Misiewicz of Misha Design |

One of the common complaints from design teams is that by the time a project gets to completion in Ireland, it is often out of date. The design for Cashel Community Hospital, for example, was drawn up in 1996, but the fi rst phase of the project was not completed until nearly a decade later, and the second phase is still under construction.

Design-build aims to shorten that time by removing some of the steps in the assessment and approval process, and bringing the interaction with the end-user in at an earlier stage. And, says Desmond Fitzgerald, acting deputy chief architectural advisor for the Health Service Executive, it should enable more fl exibility to ensure the design continues to meet the client’s needs.

Unlike in the UK, public-private partnership (PPP) funding has not been used much in Ireland for the development of facilities in the healthcare sector, However, it is being considered as part of the strategy to build specialist centres for radiation and oncology. How design fares in this regime comes down to how the tender documentation is put together, says Fitzgerald: “If the tender is structured correctly, we can maintain quality and service with the best equipment available,” he explains. “We are always keen to have good quality and I don’t think it costs any more.”

Assessing a changing landscape

Throughout Ireland, in both the North and the Republic, the healthcare landscape is changing, as old buildings and methods of healthcare delivery are brought into the 21st century, revealing innovative new design at both ends of the geographical spectrum. The focus, according to those leading the change in both countries, is on improving and making more efficient the delivery of care to patients and communities.

As John Cole says: “Buildings are not ends in themselves. They are a response to a need. Understanding that need will lead to better buildings – and better buildings heal better.”

Kathleen Armstrong is a health writer and journalist

|

1.1.jpg)

|